For my friend Giorgio Terruzzi

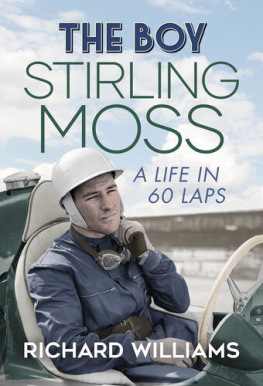

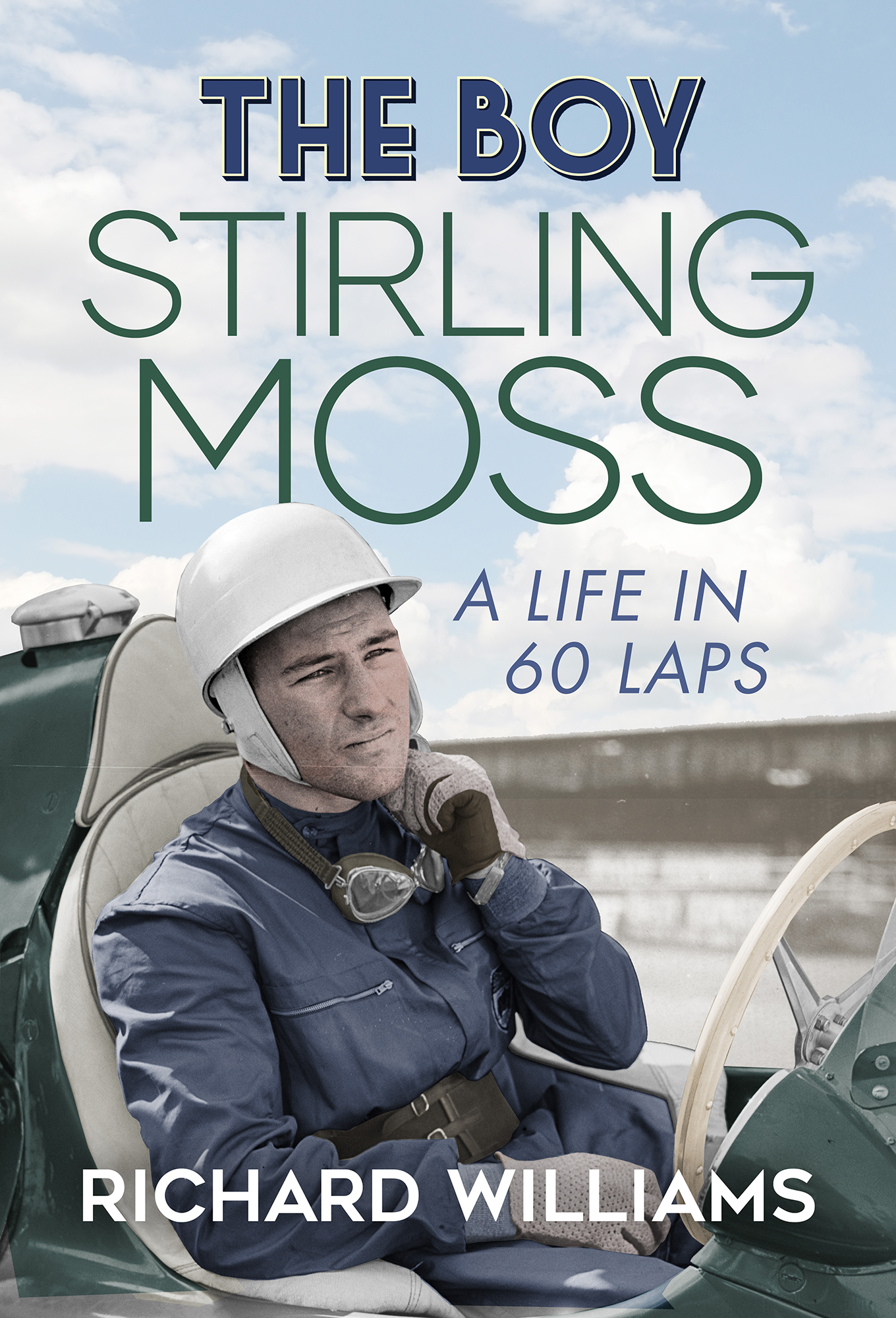

An automobile race in which Stirling Moss drives a car can have one of two endings. Either Moss wins, or Moss breaks down and someone else wins

ALFRED WRIGHT , Sports Illustrated, 1959

CHAPTER 1 THE LAST TROPHY

Shepherd Market is a small village in the centre of London, on the edge of Mayfair, bounded by Curzon Street to the north and Piccadilly to the south, where for a couple of centuries the signs of discreet wealth and loose morals have happily co-existed. On a summers day in 2017 I walked up one of its narrow streets with a bag containing a silver statuette, about 18 inches tall: the figure of a racing driver from a bygone era, in helmet and overalls, goggles slung round his neck. I was on my way to deliver it to the house of the man on whom it had been modelled and who, long ago, was known to the newspapers and their readers as The Boy.

A week earlier Id been due to accompany Sir Stirling Moss and his wife, Lady Susie, on a trip back to Pescara, halfway down Italys Adriatic coast, for the sixtieth anniversary celebration of a famous victory. The race in 1957 had fascinated me ever since, barely ten years old, I read a report of it in my fathers daily newspaper. This was a world championship Grand Prix thrust into the calendar at the last minute, run over a 16-mile course on public roads, from a seaside resort up into the villages in the foothills of the Abruzzi mountains and back again. Moss drove a Vanwall, a British car, beating the powerful Italian teams on their own patch for the first time. Later Id written a book about it, filled with stories and memories including his from a vanished age. After it was published, I was invited to Pescara to take part in a film about the history of racing in the city; now Id been asked to return for the anniversary, accompanying the guests of honour.

Sadly, Stirling couldnt make the trip. Six months earlier hed been taken ill on the way home from visiting Australia. What seemed at first like a straightforward respiratory infection had worsened and turned into something else. After several weeks in a Singapore hospital, hed been brought back to London by a specially chartered medical aircraft. Now he was at home, receiving permanent twenty-four-hour nursing care. He was eighty-seven years old and, as it turned out, he would never be seen in public again.

I was asked to go to Pescara anyway, suddenly promoted to stand in for a legend whose face was on the posters, the programmes, the VIP passes and the labels on the bottles of red wine produced in celebration by a local vineyard. Sadly, he missed out on the sort of reception normally accorded to royalty during a series of lunches, dinners and parades of old sports and racing cars Maseratis, OSCAs, Alfas, Fiats through the town and up into the hills, watched by delighted locals and holidaymakers. That welcome came my way instead, including a room at an elegant beachfront hotel, the Esplanade, where one could easily imagine the likes of Moss and his fellow drivers, the generation of Fangio, Hawthorn, Castellotti and Collins, sitting together in the bar on the night before a race. The disappointment at the absence of Sir Moss, a man whose reputation in Italy had been established in the days when he was still a teenage prodigy, was intense and widespread, although the organisers were more than generous to his designated substitute.

During the farewell ceremony I was handed the specially commissioned statuette that was to have been presented to him as a permanent keepsake, and asked to take it back to London for him, along with a commemorative plaque and a couple of bottles of the special wine. Then I was shown to the car which had picked me up in Rome two days earlier and in which I was now to be driven back through the mountains to catch a direct flight home to London.

During that four-hour journey across the centre of Italy, I couldnt help reflecting that this was part of the route on which he had won one of his greatest triumphs: the epic Mille Miglia of 1955, thundering to victory in his silver Mercedes over unprotected public roads and through remote villages. Although some of them had since been smoothed out and bypassed, the scenery was still formidable in its remoteness. By the time he reached the Rome control, halfway around the thousand-mile course, he had a lead of seventy-five seconds and was about to defy an old maxim: He who leads at Rome will never win the Mille Miglia.

When I rang the bell at his house, a nurse came to the door. Susie sent her apologies. My visit coincided with a moment when she couldnt leave his bedside. I handed over the trophy and walked away as the door closed on a house full of the memories of his 212 victories from 529 races between 1947 and 1962: the cups and shields, the models of his cars, the diaries recording the events of a racing career, the carefully compiled scrapbooks, and the bent steering wheels from his two biggest crashes, at Spa in 1960 and Goodwood in 1962, mounted and hung on the walls like stags heads, symbols of his courage in the face of danger. Now one more object had been added to the gallery. I had taken the Boy his last trophy.

CHAPTER 2 UNSPOILT

Heroes were in short supply in 1947, a Derbyshire doctor wrote in a letter to the Guardian during the coronavirus spring of 2020, commenting on a nostalgic article about a season illuminated by the exploits of the cricketer Denis Compton, a dashing figure whose endless flow of runs kept the nation enthralled. As the long years of war began to recede, sport in Britain was getting moving again. Compton and the mesmerising footballer Stanley Matthews were in their pomp, playing to packed houses after picking up the threads of careers that had begun in the 1930s. But Stirling Moss was a fresh face.

The Boy made his competition debut on 2 March 1947 in the Harrow Car Club Trial. He was seventeen years old, his shock of dark hair uncovered as he took the wheel of a BMW 328, a strikingly handsome two-seater sports car. Before the war, this had been a potent machine. Its two-litre straight-six engine had been powerful enough to carry it to a class win in the 1938 Mille Miglia. The car Stirling drove was a right-hand-drive model acquired by his father from a fellow dentist and amateur racer.

In the late 1930s, German racing cars had become unbeatable. Curiously, only a year or two after the end of the war, there was no stigma attached to them among most British car enthusiasts, even though their manufacturers had also made engines for the Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs that did battle with the RAFs Spitfires and Hurricanes an attitude of reconciliation that would be underlined when Moss joined the Mercedes-Benz team a few years later. Now, in his BMW, Stirling won something called the Cullen Cup, which happened to have been donated by his mother.

Compton had just finished punishing the South African bowling with a double century in the second Test, with thousands unable to get into a packed, sun-baked Lords, when Stirling entered the BMW in his third event. The Junior Car Club rally in Eastbourne included various forms of test among them parking, steering and acceleration on the resorts seafront promenade. He was named first in class.

Soon, while still in his teens, he would be winning trophies from Goodwood to Lake Garda and an eager nation would be applauding a prodigy. At twenty, he was presented to the King and Queen before the British Grand Prix. Too young to have served in and been scarred by the war, he was exhibiting the combination of skill, courage and panache celebrated in the generation that had fought in the air and on land and sea. Their youth had been stolen; his was new and unspoilt.