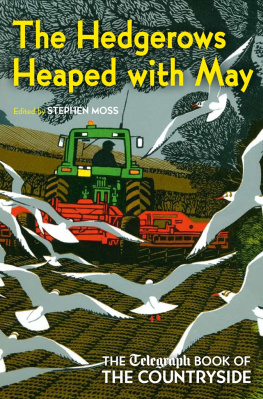

The Hedgerows Heaped

With May

I would like to thank Caroline Buckland, Kylie OBrien and Gavin Fuller at the Telegraph for all their help with this project Gavin in particular for all his assistance finding all these pieces in the papers archive; and Graham Coster, Melissa Smith, Lucy Warburton and Anandi Vara at Aurum.

S.M.

The by Max Hastings is from Editor (Macmillan, 2002).

The Tragedy of the Gold-Crested Humble by Clive James (Copyright Clive James 2011) is reproduced by permission of United Agents (www.unitedagents.co.uk) on behalf of Clive James.

Please Keep Off the Mud James May

God made the country, and man made the town

William Cowper, 1785

One area in which we are achieving real success, wrote Max Hastings in 1987, not long after assuming the editorship of The Daily Telegraph, is coverage of the countryside. This, he went on, was a welcome corrective to most British newspapers, overwhelmingly written by and for an urban and suburban constituency. Yet even many of those who dont live in the country wish they did, and we do well to show we can identify with them.

For Telegraph readers, who might reasonably be described as tending towards the traditional and conservative, the word country has a very special resonance. It means not only the non-urban landscape but also, quite simply, the nation. And, to them, the one stands emblematically and literally for the other. The Americans may have the wilderness, the Australians the bush, and the French la campagne or le paysage; but none of these has quite the mystical, the mythical, the political resonance even, of the simple English word countryside.

Until quite recently, in the pages of the Telegraph, the countryside essentially meant one man: J.H.B. Peel. From the early 1960s until his death in 1983, John Hugh Brignal Peel contributed a fortnightly essay, Country Talk, from his home on Exmoor.

Born in 1913, Peel was the archetypal countryman. Born into an old North Devon family, he spent his whole life apart from education and War service in the area along the border of Devon and Somerset made famous by R.D. Blackmores novel Lorna Doone.

Indeed, the poet John Masefield wrote of his friend that Peel knows more than any other living man about the life of the English countryside. This is an interesting claim because it suggests that there was a settled and finite amount of knowledge about the English countryside, and that one man was capable of possessing it, even if it is a notion we would consider absurd today.

Peel, though, wrote about a countryside that was timeless and unchanging. His job was both to celebrate it and to explain it to his readers; he did so delightfully, for example, in a whimsical yet erudite survey of the ancient origin of field names.

How very different Peels approach is to todays Telegraph, and how different his background to the list of more recent contributors in this volume. These include the presenter of a hugely popular TV motoring programme, an Australian TV critic, the man who founded the Glastonbury rock festival, and even the mayor of London. And just look at some of the subjects covered here, each of them reflecting an aspect of todays countryside: from property prices to bus shelters; from camel breeding to swingers parties.

What this remarkable diversity of contributors and subjects reveals is that nowadays not only does the countryside mean something different to everyone indeed, every square foot of it is fought over by competing interests but also that, as with every other facet of British society, constant change has become its defining characteristic. Indeed, already since Malcolm Smith wrote his piece about rare birds in Britain in 1999, the little egret has become a common sight and the spoonbill has bred several times, while the otters whose survival prospects seemed so pessimistic to Brian Jackman in 1993 are now present on most rivers in Britain, with road traffic the newest risk to their numbers.

So the landlord of a country pub can be a refugee from the City of London, downsizing to avoid stress. Conversely, as Top Gear presenter James May suggests, he may have brought the stress with him because, in Mays words, the countryside belongs to the car. The subject of rural crime rears its ugly head within these pages, but the perpetrators are now more likely to be from the local community rather than the big city.

Opinions differ radically, too: Joanna Trollope passionately defends the Countryside Marchers; Ross Clark mounts an equally heartfelt diatribe against them. And among several pieces on the joys of moving from town to country is a contrary view, by Sinclair McKay, about how he found the countryside a rather disagreeable and forbidding place.

As with James Mays contribution, a consistent pleasure of the pieces collected in this book is reading about traditional, apparently timeless rural institutions examined from very modern, worldly perspectives.

So, as you might expect, we examine The Archers, but via the stethoscope of the Telegraphs medical editor Rebecca Smith. She ponders the longevity of the soap operas characters, noting that they are rather more likely to die in a nasty accident than the average Briton. Then there is the country vicar. However, instead of the clichd figure of the elderly male cleric from a Thomas Hardy novel, the Church of England is represented here by the formidable (and unquestionably female) figure of the Vicar of Dibley.

Just as intriguing is reading about how some of our most distinguished naturalists unearthed wildlife in the least rural of surroundings. Who could have imagined that Canvey Island home of oil refineries and the pub-rock band Dr Feelgood could also be, as Peter Marren reveals, a bug-hunters paradise?

In recent years Britain has seen a resurgence of what is usually called nature-writing, a tradition that stretches back through Kenneth Allsop, Gavin Maxwell and Richard Jefferies all the way to Gilbert White. Peter Marren is joined here by Richard Mabey, with a learned dissertation on birds and their folklore, and John Lister-Kaye, observing how Scotlands wildlife copes with harsh winters.

Above all, as you would expect from the Telegraph, this book contains a great deal of robust common sense and strongly held opinions. Bernard Ingham fulminates against the giant lavatory brushes marching across our hills in the guise of wind turbines. W.F. Deedes brings his magnanimity and experience to the question of multiculturalism in a countryside context. And Geoffrey Wheatcroft makes an elegant defence of Nimbyism.

We may not always agree with the forthright views of one of J.H.B. Peels successors, Robin Page, but no one can doubt his depth of knowledge and passion for his beloved countryside. His account of a major incident alert mounted by a primary school when one of its pupils picked a deadly fungus which later turned out to be an edible mushroom is all too credible.

Certain things about the countryside will always appeal to Telegraph readers, and I hope they will be reassured to learn that there are pieces about birdsong and butterflies, green country buses and village shops, grouse shooting and fly-fishing, willow trees and the WI, as well as poignant elegies to the cuckoo, the skylark and the English elm.

Every reader will have his or her favourites. I particularly enjoyed Mia Daviss witty, self-deprecating and ultimately futile search for love as a single woman in rural England, and David Waltons delightful ramble through the Somerset countryside, fuelled by copious draughts of cider.

Next page