by Dr Rebecca Welshman

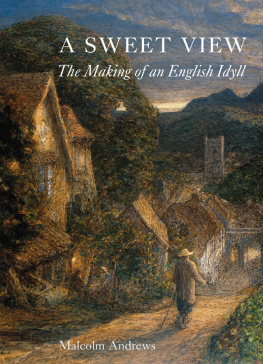

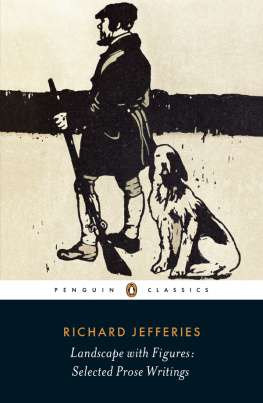

Richard Jefferies (18481887) was an author and naturalist, born in Wiltshire. He wrote The Gamekeeper at Home, The Amateur Poacher, Round About a Great Estate, and numerous other works. Jefferies was a pioneer in countryside and nature writing, and his style has been widely embraced and replicated by writers over the last century. He wrote with great feeling and insight about the nature and landscapes of the Wiltshire Downs, and later about the natural history and human life around Surbiton, Brighton, and London.

Jefferies writings on sport are from firsthand experience. As a teenager he spent time observing the habits and habitats of birds and animals, and through his friendship with the gamekeeper on the Burderop estate he learnt the techniques of shooting. After befriending local poachers and sportsmen, he became familiar with the methods of poaching, and the culture of rural sporting traditions. He also learnt much from his father who cultivated the land and gardens around the family home, Coate Farmhouse, near Swindon, which can still be visited and enjoyed today.

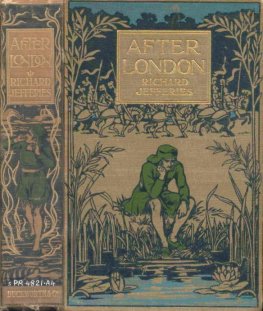

For Jefferies, sport was more than just a pastime. It gave him a reason to be out in the fields or woods, or by the water, and allowed him to enjoy and reflect upon the treasures of the natural world. Sport is present in some form in the majority of his books. We might remember the relentless physical pursuits of the two boys in Bevis who shoot, fish, swim, and sail, or Felix, the accomplished archer in After London, both of whom were modelled on Jefferies himself. In his essay A Defence of Sport, written for the National Review in 1883 as a response to the debates surrounding the cruelty of fieldsports, Jefferies refers to sport as an instinct that betters mental and physical health, and suggests that a person will be better equipped in all areas of life if they are first well educated in the life of the outdoors.

This is the first anthology to focus on Jefferies writings on sport. With extracts from well known and lesser known works, and newly discovered articles republished for the first time, the collection represents Jefferies experiences of shooting ground game and wildfowl, hunting, poaching, fishing, and hare coursing. The selections also highlight Jefferies interests in estate management and the lives of people who lived in the countryside. Printed alongside are seasonal pieces and some of his more reflective observations.

Jefferies sketches of sportsmen, squires, gamekeepers, and poachers are based on people he knew and spent time with. As an agricultural journalist in the 1870s he attended events, such as fairs, markets, shows, and exhibitions. Many of the farmers and labourers who he would have met along the way would have participated in rural sports. In his notebook from 1876 Jefferies records attending the Epsom Derby, which was one of Britains largest sporting fixtures. Horses fascinated Jefferies; their strength, endurance and beauty of form were qualities which he envied. In the Amateur Poacher Jefferies writes: The proximity of horse-racing establishments adds to the general atmosphere of dissipation. Betting, card-playing, ferret breeding and dog-fancying, poaching and politics, are the occupations of the populace. The sporting territories of the Wiltshire Downs lay close to Jefferies birthplace. At Lambourn, which is known as the Valley of the Racehorse, horses have been trained since the eighteenth century. Also close by is Ashdown Park, the home of the Earl of Craven, which in the nineteenth century was one of the best known venues for coursing meetings. In Walks in the Wheatfields Jefferies writes that hares are almost formed on purpose to be good sport and that coursing is capital, the harriers first-rate. His passion for the sport is also evident in the hare-coursing scenes in The AmateurPoacher, which Edward Thomas called the finest thing in the book.

Jefferies also appreciated fox hunting not because it was a blood sport but because as a rural tradition it had a unique aesthetic and atmosphere. In 1876 Jefferies made a note on the insight into social history that hunting afforded, saying that to hunting we owe no little knowledge of men and manners. He bemoaned the fact that landscape painters seemed to avoid painting the gritty details of hunting scenes: no one paints the foggy days, the dead leaves, the soaking grass its melancholy landscape. Why does not someone paint the natural hunt? With the cottager and his bill hook looking up, and even the scarlet dulled by the rain or splashed by a fall and the fence tearing the coat.

In his sporting contributions Jefferies makes clear and striking observations about movement, position and individual response to the environment. These qualities are particularly evident in his contributions on shooting. Soon after his country books were serialised in the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1870s, Jefferies was asked by the publisher Charles Longman to write a manual on shooting. Although this project was never finished, fragments of manuscript were printed in 1957 by Samuel Looker, some of which are reproduced here in this collection. However, although he grew to be an accurate shot, Jefferies also expressed his desire to simply observe birds and animals. In The Amateur Poacher he describes the moment when he lets the gun go just to watch the flight of a pheasant:

My finger felt the trigger, and the least increase of pressure would have been fatal; but in the act I hesitated, dropped the barrel, and watched the beautiful bird. That watching so often stayed the shot that at last it grew to be a habit: the mere simple pleasure of seeing birds and animals, when they were quite unconscious that they were observed, being too great to be spoilt by the discharge. After carefully getting a wire over a jack; after waiting in a tree till a hare came along; after sitting in a mound till the partridges began to run together to roost; in the end the wire or gun remained unused. The same feeling has equally checked my hand in legitimate shooting: time after time I have flushed partridges without firing, and have let the hare bound over the furrow free.

I have entered many woods just for the pleasure of creeping through the brake and the thickets. Destruction in itself was not the motive; it was an overpowering instinct for woods and fields. Yet woods and fields lose half their interest without a gun I like the power to shoot, even though I may not use it.

In 1883 Jefferies spent the summer on Exmoor researching the area. After being introduced to Arthur Heal, huntsman to the Devon and Somerset Staghounds, Jefferies experienced firsthand the finer details of the chase. These experiences became the foundation of his book Red Deer. In the book he refers to the complete catalogue of sport that took place in Red Deer land including salmon fishing, otter hunting, stag hunting, black game shooting, as well as pheasant and partridge shooting. For Jefferies Exmoor ways of life were refreshingly remote from the ordinary grind of urban living, and illustrated an ancient form of human occupation and relationship with the land.

Sadly, for someone who so loved the outdoors, Jefferies failing health meant that he was confined to the indoors during his last few years. In Hours of Spring he describes watching the unfurling of the season from his place by the little window of his cottage at Goring: Today through the window-pane I see a lark high up against the grey cloud, and hear his song. It is years since I went out amongst them in the old fields, and saw them in the green corn. As his illness worsened the benefits and pleasures of sport became memories rather than realities. Yet the faculties employed in sport instinct, precision, and focus and the beauty and grace of animals and birds, continued to inspire Jefferies until the very end of his life. For the love of sport is often closely associated with a love of the countryside as Jefferies writes in