PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park,181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

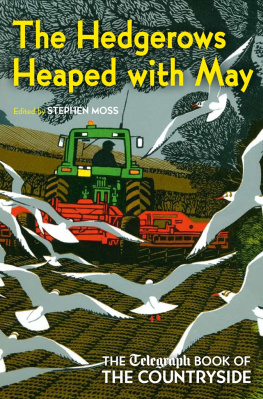

This selection, originally entitled Landscape with Figures: An Anthology of Richard Jefferiess Prose, first published in Penguin English Library 1983

First published, with a new preface, in Penguin Classics 2013

Introduction copyright Richard Mabey, 1983

New preface copyright Richard Mabey, 2013

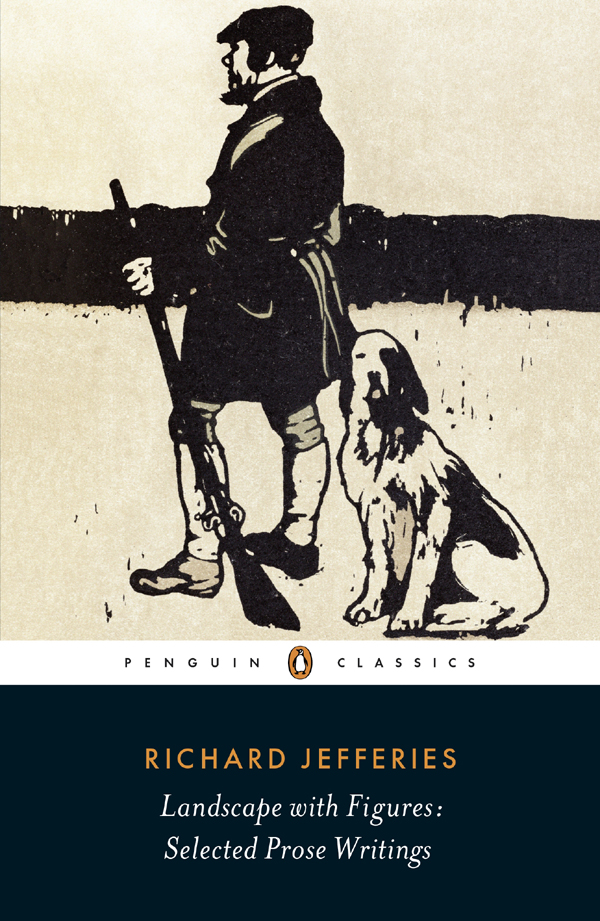

K is for Keeper, illustration from An Alphabet, published by William Heinemann, 1898 (hand-coloured woodcut), Nicholson, Sir William (1872-1949) / Private Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author of the editorial material has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

ISBN: 978-0-141-39290-5

PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES: SELECTED PROSE WRITINGS

RICHARD JEFFERIES (184887) was probably the most imaginative and certainly the least conventional of country writers. He never worked the land and did not always live in the countryside, but in his articles and essays he single-handedly created the modern idea of English nature writing.

He wrote an astonishing amount in his short life, including novels (most famously Bevis and the hugely influential post-apocalypse novel After London), an autobiography, The Story of My Heart, and numerous essays on the English countryside, both about the people who lived and worked there and about its animals and plants.

After an education at Oxford, RICHARD MABEY worked as a lecturer in social studies, then as a senior editor at Penguin Books. He became a full-time writer in 1974 and is the author of some thirty books, including Weeds: How Vagabond Plants Gatecrashed Civilisation and Changed the Way We Think About Nature (2010); Whistling in the Dark: In Pursuit of the Nightingale (1993), winner of the East Anglia Book Award, 2010, in a revised version entitled The Barley Bird: Notes on a Suffolk Nightingale; Beechcombings: The Narratives of Trees (2007); the ground-breaking and best-selling Flora Britannica (1996), winner of a National Book Award; and Glibert White, which won the Whitbread Biography Award in 1986. His recent memoir, Nature Cure (2005), which describes how reconnecting with the wild helped him break free from debilitating depression, was short-listed for three major literary awards: the Whitbread, the Ondaatje, and the J. R. Ackerley prizes. He writes for the Guardian, New Statesman and Granta, and contributes frequently to BBC radio. He has written a personal column in BBCWildlife magazine since 1986, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2011.

Preface to New Edition

Richard Jefferies died of tuberculosis in 1887, aged thirty-eight. In a writing life of little more than twenty years, he showed signs of becoming a literary polymath, publishing nine works of fiction and more than 450 essays and pieces of journalism. They range from a tone poem on The Lions in Trafalgar Square, through slight nature notes and political brickbats on the misdemeanours of agricultural labourers, to metaphysical meditations on human perception. What links them is a nagging, inquisitive and, just occasionally, toxic curiosity about what, in the great scheme of things, was the relationship between human beings, nature and the land.

Its not surprising that in Jefferies own breakneck career this passion moved through distinct phases. It began in his teens, with strictly journalistic and often deeply conservative surveys of the worlds of farming and gamekeeping, shifted to sharper enquiries into natural history, and concluded with a kind of inclusive synthesis, in which human nature, the more-than-human world, and the deep mysteries of consciousness all become part of a single field-play. Jefferies was trying urgently to work out who he was, as a displaced, rootless, professional peerer, being rapidly invaded by one of the more destructive manifestations of nature.

Jefferies first perched on my shoulder when I was about twelve years old, and has lurked (not always enjoyably) in the shadows ever since. What fascinates me is how Jefferies phases movements, if you like have been echoed both in my own life, and in the shifting focus of public interest. When I first came across him, I was an adolescent nature-romantic, inclined to solitariness. His numinous landscape writing touched something quite deep and undefined in me, and I aped his style shamelessly in school essays. When I was sixteen I won a prize for one of these pastiches, and chose Jefferies spiritual autobiography, The Story of My Heart, as my reward. It is a measure of how tastes change that the staff in charge of prizes had never heard of either it or its author, and suspected from the title that it was some cheap novelette. So it had to be vetted. They might just as well not have bothered. I found it incomprehensible once Id been presented with the thin volume, and it still seems to me a faintly distasteful piece of pre-New Age self-indulgence.

Half a century on, the reading public is more aware of Jefferies, especially his special contribution to what is now known as nature writing, as distinct from natural history writing. I find Im constantly discovering new aspects of him here as well. His instinctive grasp of ecology was always obvious. Even in his most despairing moments, he understood the individual humans inseparability from the rest of creation, however indifferent creation was to him. But a sharpening of our contemporary interest in what, precisely, these links are has helped highlight what a precocious observer Jefferies was. He was a kind of hedge-scientist, reasoning through analogy, forging explanations by the application of reason and intuition to acute observation. Its not a respectable scientific mode these days, but it creates a space where human imagination can meet the constantly evolving, experimenting pool of life. Jefferies was surprisingly modern in his ideas about perception, too. He was aware of the dangerous subjectivity but also creativity of the senses, of how cultural context, psychological preconception, even pure optical illusion, shape the way nature appears to us. The mutability of the perceived world and of evolving life itself were, in the end, a single phenomenon to him.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS