A SWEET VIEW

The Making of an English Idyll

Malcolm Andrews

REAKTION BOOKS

For my family, past,

present and to come,

with love

and welcome Tristan!

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright Malcolm Andrews 2021

All rights reserved

Published with support from the Marc Fitch Fund

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789144970

Contents

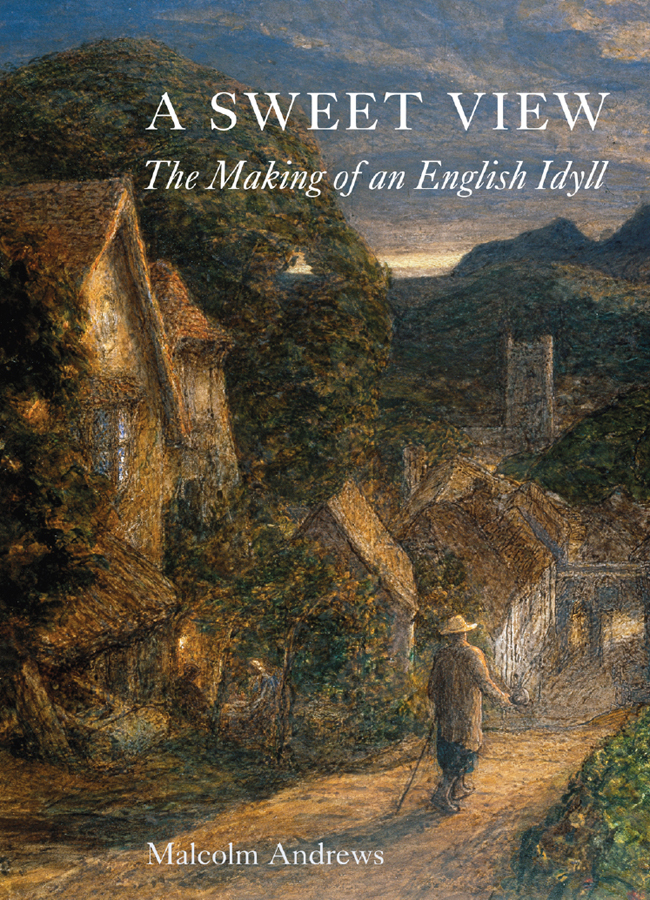

1 Detail of Myles Birket Foster, Lane Scene at Hambledon, c. 1862, watercolour on paper.

Preface

T he phrase a sweet view is taken from Jane Austens Emma (1816), as the heroine gazes at a landscape in one of the southern counties and muses fondly on its English verdure, English culture, English comfort. Emma was written during the last years of the Napoleonic Wars, a period when national identity in landscape terms needed a visible face. Over the ensuing century a distinctive repertoire of rural motifs evolved and then congealed into icons of Englishness downland, farms, orchards, thatched cottages, village church spires, gently undulating meadows bordered with hedgerows. By the time of Emmas centenary this pictured countryside was being summoned into national service; recruitment posters for the First World War displayed the imagery to represent the country people were fighting for.

Here is how one novelist of the time, H. G. Wells, presented it, with something of the same soft-focused fondness as in Emmas gaze:

There is no country-side like the English country-side for those who have learned to love it; its firm yet gentle line of hill and dale, its ordered confusion of features, its deer parks and downland, its castles and stately houses, its hamlets and old churches, its farms and ricks and great barns and ancient trees, its pools and ponds and shining threads of rivers, its flower-starred hedgerows, its orchards and woodland patches, its village greens and kindly inns. Other country-sides have their pleasant aspects, but none such variety, none that shine so steadfastly throughout the year... none of these change scene and character in three miles of walking, nor have so mellow a sunlight nor so diversified a cloudland.

This paean to the English countryside comes near the opening of Wellss novel The History of Mr Polly (1910). It conveys a sense of the native landscape as a finished work, a securely established and unique scene laid out for the pleasure of those who have learned to love it. Three of those who have learned to love it are Alfred Polly himself and his two friends all three young men doomed to toil behind counters... for the better part of their lives. This doom meant that, as Wells put it, they had no footing in the countryside through which they were walking. They were visitors, outsiders, all the more alert to what was different from their familiar domestic and working environment and thereby constructing their English country-side. The experience of these young men recapitulated the larger national experience over the course of the nineteenth century in England, as a predominantly rural population drifted from the countryside into the rapidly expanding towns and cities. People adapted to urban life, but as part of that necessary evolutionary process they had less and less direct experience of the rural world that continued, remotely, to supply their food, their cut flowers, their diminishingly clean air and water. Over time the countryside flattened into scenery for their leisure excursions. That two-dimensional countryside burgeoned in the canvases, photographs and illustrated books that lavished attention on an anthologized rural England.

Now, two centuries on from Emma, English national identity has once again come into sharpened focus. Both Brexit and the future of the United Kingdoms internal union raise questions and challenge prejudices about England and Englishness. For those who have learned to love it, consciously or otherwise, English country scenery may well be requisitioned yet again in the quest for clarification of identity.

A Sweet View is about that learning process. My fundamental aims are quite simple: to suggest an evolutionary account of the emergence in England of a certain rural idyll, partly by tracing the changing ideas of the picturesque in the nineteenth century; to listen with the reader to some of the most passionately engaged makers of that idyll; and to spend time with their paintings and word-pictures so as to understand more why they had such affective power. surveys the principal features of English countryside, predominantly its southern countryside, once its iconic character has been established in Victorian England: the village green, old pathways, gates and stiles, country church and churchyard, hedgerows and, to conclude, the country cottage as a nexus of values associated with the changing ideas of Englishness.

Surrey features prominently in this book. Three of my principal figures, Palmer, Foster and Jefferies, settled and worked in the county. The chocolate-box imagery of cottage England for the Victorians was generated largely from the countryside around the Surrey villages of Witley and Sandhills, the homes of (respectively) Foster and Helen Allingham. The localization of this generic English rural idyll is important. When Mr Pollys narrator declares There is no country-side like the English country-side, he makes a doubly contentious point. First, he asserts an English uniqueness among international competitors; second, he assumes English countryside is just a single identifiable entity, the English countryside, instead of a combination of many very different landscape profiles and personalities. That latter point has been articulated well by Paul Readman in Storied Ground: Landscape and the Shaping of English National Identity (2018). In studying different English landscapes, each with their own distinctive identities, Readmans book takes for granted the cultural dominance of the South Country idyll as the traditional, conventional expression of Englishness in landscape, and seeks to articulate the claims of alternatives. South Country is the name that Hilaire Belloc gave to Sussex and the South Downs. Edward Thomass book The South Country (1909) took the term and stretched it to cover the southern English counties from Kent westwards to Dorset. Mr Polly and his friends are supposed to be enjoying their country excursion in the regions of Hampshire and west Sussex.

My own book is a study primarily of the making of that South Country landscape idyll (drawing mainly on Kent, Surrey and Sussex). South Country has strong personal associations for me, and that is one of the motives for writing this book. After the Second World War my grandfather, who worked in south London, bought an old farmhouse in the Surrey countryside. He drove daily through its lanes to and from work in his Camberwell office. The farmhouse (which lingers as an intensely romantic memory for this grandson) had a mighty old barn, filled in autumn and winter with soft-play mountains of hay squares. Its huge doors looked out across the wide cobbled yard to the family house. A wooden granary on stilts formed the third side of the yard. It was only two miles or so from Fosters Witley village and Allinghams Sandhills hamlet. Grandfather Andrews bought into the idyll, just as Foster and Allingham had done when they moved into the area several generations earlier.