Page List

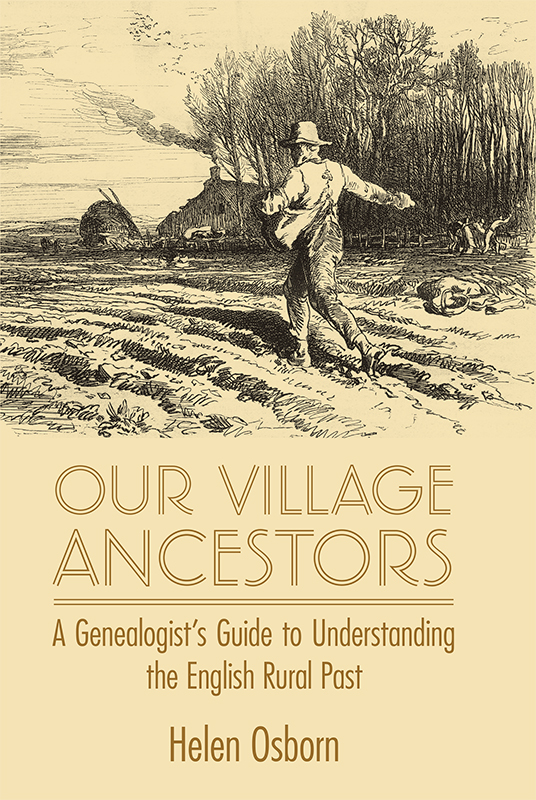

A Genealogists Guide to Understanding the English Rural Past

Helen Osborn

ROBERT HALE

First published in 2021 by Robert Hale,

an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd,

Ramsbury, Marlborough,

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

enquiries@crowood.com

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Helen Osborn 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 3148 5

The right of Helen Osborn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover design by:

Catherine Williams, Chapter One Book Production

The Rural Past

T his book is aimed at those who have discovered a love for filling in the details about the lives of their ancestors as they build trees; even the novice family historian should be able to take something away from it, although it is not a how to guide in starting genealogy research. There are many books and resources that show how to start researching a family tree, and it is expected that the reader will have already progressed beyond the stage of simple name gathering, and will be ready to discover increasing amounts of local and historical context and how to open up the records to gain the maximum from them.

The subject is a wide one: English village life from the middle of the sixteenth century up to the nineteenth century, viewed through the lens of documents that genealogists commonly use. This 400-year sweep of time resulted in the creation of almost all the local records we use to build the pedigree of a family, whether that family is rooted in landed gentry and the lords of the manor, or came from the ranks of the humble farm servant.

The period begins with the setting up of parish registers in England and Wales in 1538 during the reign of Tudor king Henry VIII, and ends with the nineteenth-century census and the administrative reforms that centralized administration and records, making them less useful at the local level. Along the way we will meet some of the most important records that give information for genealogical tree building and evidence of relationships, as well as illustrating how life was lived in the countryside, through the stories they tell.

Notwithstanding the blood kinship links that DNA investigations have brought to the study of genealogy, genealogists remain overwhelmingly reliant on written sources and luckily there are a huge number of sources for England. From the Middle Ages onwards the growth in those sources allows an increasing amount of light to be shed on our ancestors lives. As the centuries unfold, the documentary sources for both village history and family history simply within a rural parish multiply, and do not stop being of use until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the parish lost many of its administrative functions.

As well as the parish registers, there are other records of the parish, such as surveys and tithes, accounts and records of the poor law, and records of local charities. Outside the parish system there were the records of the manor, concerning themselves not only with tenancies and cultivation of land, but also with the misdemeanours of villagers.

This book doesnt describe all the possible records in which people can be found for the whole of a 400-year period, but tries to put some of the most common and usable local records into a useful context. The emphasis throughout is on thinking about geographic and historic context, and the records that are created and held locally.

I do not deal with records created by the Victorian national administrations, such as civil registration, which started in 1837, although we will meet the Victorian census because it gives us so much useful information about a place. Nor do I describe many records created at the local but wider levels of diocese or county, except where they are particularly important to showing how life was lived, such as with probate inventories and the records of quarter sessions. Many of these records are of equal importance to the history of towns and cities: they are certainly not all unique to the village.

The family historian who desires to get under the skin of their ancestors and understand their way of life, as well as to interpret the records correctly, needs to switch their focus away from names and on to geographical places. In that respect, this book is an antidote to the myriad online data websites, which encourage quick searching for names. I am convinced that research into the people of a place research that unfolds in a more leisurely fashion, allowing the family historian to truly understand both the records and the location is ultimately the most rewarding.

The Importance of Place

T he sixteenth century witnessed a huge rise in record creation, documentary sources and writing of all kinds useful to both the genealogist and the historian. It is possible to combine information from these sources so that pictures of even ordinary individuals can be built up. The survival of all these records varies a great deal from parish to parish and village to village, yet it is still true that most English parishes have extensive sets of records from the sixteenth century up to the present. Even if records from the nineteenth century appear different from the earlier types, they were still created for the same purpose: to deal with the same kinds of problem that a community needs to deal with day to day. The good news for the genealogist is that they record individuals, sometimes in detail.

The way we should approach these records and interpret them is the same, whether the local system varies from north to south or east to west, although it is necessary to keep a firm sense of place and to understand that the interpretation and practice of the law in one area might differ from another.

As I showed in my book Genealogy: Essential Research Methods, genealogists often need to analyse documents in a very exacting way. This gives us special needs, which differ from the needs of local historians, because genealogists are always concerned with small personal details and minutiae. Historians choose topics and themes, and thereby select which sources to study; however, genealogists do not get to choose their sources: they are forced to use all available sources to prove a pedigree. Questions about individuals appearing or not appearing in records are of vital importance to the genealogist, while the local historian is quite rightly more concerned with whole communities rather than single families or individuals.