Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors

The Essential Genealogical Guide to Early Modern Ulster, 16001800

William J. Roulston

William Roulston is Research Director with the Ulster Historical Foundation. He is a native of Bready, County Tyrone, and has researched and written on a number of aspects of the history of Ulster in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

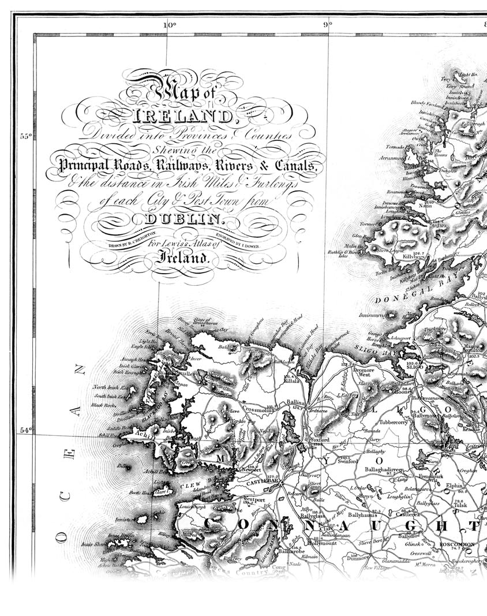

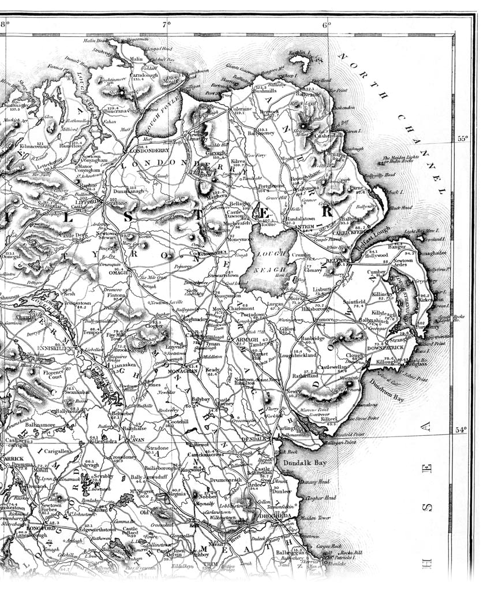

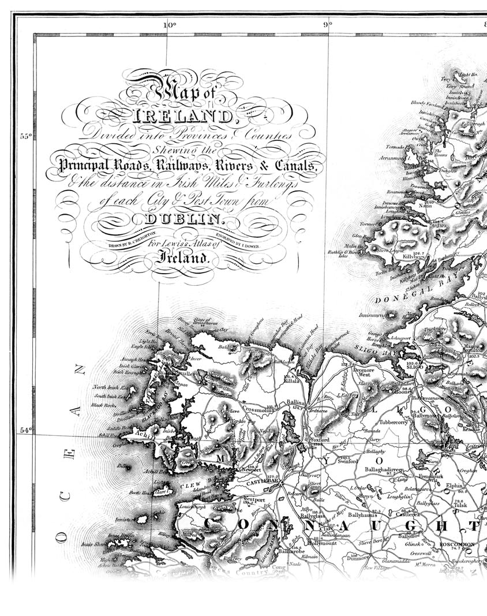

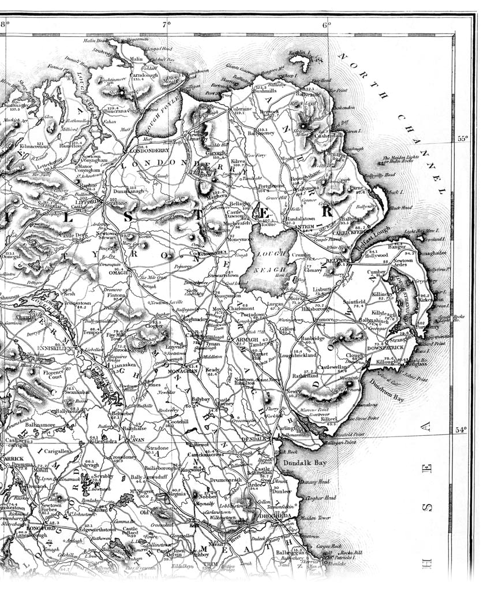

Map of Ulster from S. Lewis, Atlas of the counties of Ireland (London, 1837)

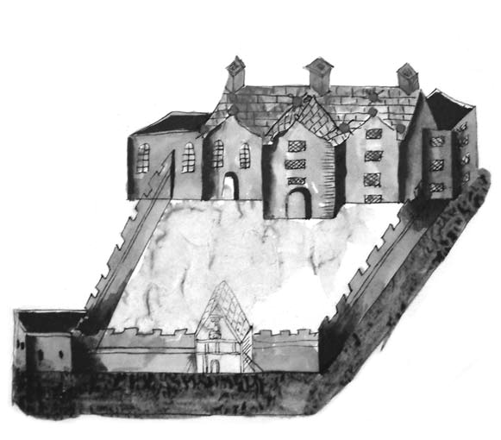

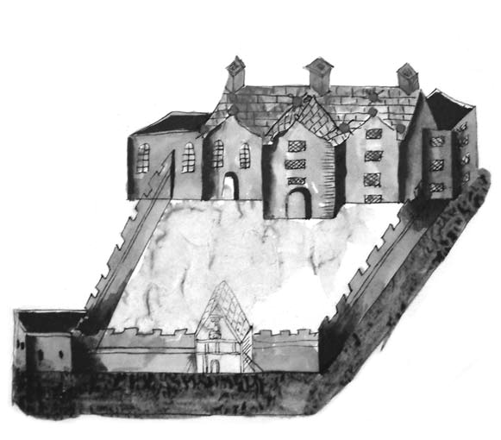

The Drapers Company castle at Moneymore, County Londonderry (PRONI)

Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors

The Essential Genealogical Guide to Early Modern Ulster, 16001800

William J. Roulston

ULSTER HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

Ulster Historical Foundation is pleased to acknowledge support for the research towards this publication from the Ulster-Scots Agency.

First Published 2005 by the Ulster Historical Foundation. Reprinted 2006, 2009 and 2010. e-book version created 2010.

49 Malone Road,

Belfast,

BT9 6RY

www.ancestryireland.com

www.booksireland.org.uk

Except as otherwise permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means with the prior permission in writing of the publisher or, in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of a licence issued by The Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publisher.

William J. Roulston

ISBN 978-1-903688-99-1

Front cover: Har headstone, Inver Church of Ireland churchyard, Larne, Co. Antrim.

Back cover: Killybegs, County Donegal, in 1622 (PRONI).

Printed by Thomson Litho

Design by Cheah Design

CONTENTS

PREFACE xi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xiv

ABBREVIATIONS xv

Appendices

Preface

The purpose of this book is to provide a practical guide for the family historian searching for Ulster ancestors in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. While the book is primarily aimed at those with Scots-Irish ancestors, its breadth of coverage means that it should be of interest to anyone researching family history prior to the nineteenth century.

The need for this volume is obvious. Many people who have successfully researched their family history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries find it difficult to take that research back before 1800. There is no denying that the loss of so many records in the destruction of the Public Record Office, Dublin, in 1922 was a catastrophe as far as historical and genealogical research is concerned. However, since 1922 the work of archivists to gather records of historical importance has resulted in a vast amount of material being available for the genealogical researcher to peruse. In addition there are other repositories in Ireland, such as the Registry of Deeds in Dublin, where the collections have survived virtually intact, as well as categories of records now available that were not in the Public Record Office in 1922 and so escaped destruction.

This book covers the sources available to researchers for the period 16001800. Some of these sources will be familiar to many genealogists, such as the hearth money rolls of the 1660s and the flaxgrowers list of 1796. Others may not. In particular, much attention is given to the value of estate papers as a genealogical source. In most guides to Irish genealogy, estate papers are barely noticed and their full potential is overlooked. Part of the reason for this is that the majority of genealogy manuals have emanated from the Republic of Ireland, where the two principal repositories, the National Archives and especially the National Library, have extensive, though frequently inaccessible, estate collections. In recent times efforts have been made to improve access to these records. The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), on the other hand, has deployed considerable resources in cataloguing the often huge collections of estate papers in its care.

While I have tried to be as comprehensive as possible, I cannot claim to have covered every single record of genealogical interest from these centuries. Such an undertaking would require a multi-volume set rather than a single handbook. The book is undeniably skewed towards sources in PRONI, but it is here that the great majority of records relating to Ulster can be found. Nonetheless I have noted records in repositories elsewhere in Ireland and occasionally in Britain and America.

Those who wish to carry out research into family history in the period before 1800 can be divided into two categories. The first category comprises those who have already been carrying out research on family members in the nineteenth and maybe even the twentieth centuries, and who wish to extend that research by going back further generations. For others the pre-1800 period will be their starting point for the simple reason that their ancestor left Ulster prior to the nineteenth century, usually as part of the Scots-Irish emigration to Colonial America.

In Irish genealogical research it is important to know not only the name of ones ancestor, but also the area in which that person lived. The ideal is to know the townland in which the ancestor lived or, if this is not available, the name of the parish (an explanation of the administrative divisions used in this volume is given in Appendix 5). However, for many people searching for pre-1800 families and this usually applies to those in the second category outlined above the only information they have is that their forebear was born somewhere in Ulster, or at best they may know the name of the county in which their ancestor originated.

There are obvious difficulties to be overcome here not necessarily insurmountable, but considerable nonetheless. Ulster is a province of nine counties, over 350 parishes and thousands of townlands. To have any chance of success it is vital that the place of origin of an ancestor can be narrowed down to a specific area. A major obstacle in trying to do this is the fact that there is no comprehensive index to names from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The first census in Ireland was not held until 1821, while official registration of all births, deaths and marriages did not begin until 1864 (non-Catholic marriages were registered from 1845).

If the precise area an ancestor came from is not known, a number of nineteenth-century sources may prove helpful. The Householders Index is based on information derived from the Tithe Valuation of c.1830 and Griffiths Valuation of c.1860. It lists surnames by parish, indicating the number of occurrences of the surname in Griffiths Valuation and simply whether or not it appears in the Tithe Valuation. Using the information in the Householders Index, it may be possible to narrow down the likely area your ancestor came from. It is particularly useful if it reveals that a surname was concentrated in a small number of parishes. Copies of the Householders Index are available in PRONI, the National Archives the National Library and, for Ulster counties, on the website of the Ulster Historical Foundation (www.ancestryireland.com).