John Burroughs - Fresh Fields

Here you can read online John Burroughs - Fresh Fields full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Read Books Ltd., genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fresh Fields

- Author:

- Publisher:Read Books Ltd.

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fresh Fields: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fresh Fields" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Fresh Fields — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fresh Fields" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FRESH FIELDS

BY

JOHN BURROUGHS

Copyright 2016 Read Books Ltd.

This book is copyright and may not be

reproduced or copied in any way without

the express permission of the publisher in writing

British Library C ataloguing-in-Publicatio n Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library

Contents

John Burroughs

John Burroughs was born on April 3 1837 in Catskill Mountains near Roxbury in Delaware County, New York, United States. As a child he played on the slopes of the Catskill Mountains and worked on the family farm. He was enthralled by the birds and other wildlife around him. Burroughs developed an interest in learning, but his father believed the rudimentary education given at the local school was enough, and refused to pay for the higher education that Burroughs desired. At seventeen he left home to earn the money needed for college by teaching at a school in Olive, New York. Between 1854 and 1856 he worked as a teacher whilst completing his studies. He continued to teach until 1863.

In 1857, Burroughs left his teaching position in Illinois to find employment near his hometown and that same year, he married the pious Ursula North (1836-1917). After five years of marital discord, Ursula concluded that her husbands sexual demands were immoral. She suggested a short separation to encourage him to value chastity. Their separation lasted until 1864, during which, Burroughs valued other female company. He remained unfaithful after their reunion. In 1901, he met Clara Barrus (1864-1931), a physician at a psychiatric hospital. She was half his age, but was the love of his life. She moved into his house after Ursula died in 1917.

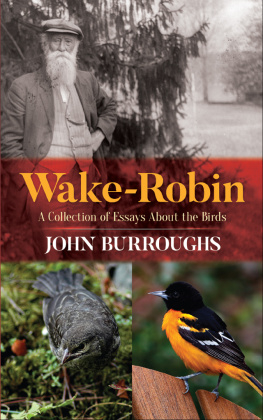

Burroughs first published essay was Expression (1860). In 1864, Burroughs began work as a clerk at the Treasury and eventually became a federal banker. He worked there until the 1880s, but continued writing and acquired an interest in the poetry of Walt Whitman (1819-1892). The pair met in 1863 and became friends. Whitman encouraged Burroughs to develop his nature writings, as well as his essays on philosophy and literature. In 1867, Burroughs published Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person which was the first biography and critical work on Whitman, and was anonymously edited by Whitman before it was published. In 1871, Burroughs first collection of nature essays, Wake Robin , was published.

Burroughs left Washington for New York in 1873 where he bought a fruit farm in West Park, New York and built his Riverby estate. In 1895, he bought additional land near Riverby and built an Adirondack style cabin named Slabsides. There, Burroughs wrote and entertained visitors. His famous friends included Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), Henry Ford (1863-1947) - who gave him an automobile, and Thomas Edison (1847-1931). In 1899, Burroughs accompanied E. H Harriman (1848-1909) on his expedition to Alaska and also travelled to the Grand Canyon and Yosemite with John Muir (1838-1914).

In 1903, after publishing an article, Real and Sham Nature History, Burroughs began a publicised debate known as the nature fakers controversy where he condemned certain writers for their absurd representation of wildlife. He also criticised the naturalistic animal stories genre. This disagreement lasted for four years and included many environmental and political figures.

Burroughs was best known for his writings on wildlife and rural life and his writing achievements were recognised by his election as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Some of his essays recalled his trips to the Catskills, for example, The Heart of the Southern Catskills , depicts the ascent of Slide Mountain. Other Catskills essays commented on fishing, hiking or rafting. He was an enthusiastic fly fisherman and contributed some notable fishing essays to angling literature, including Speckled Trout (1870). The Complete Writings of John Burroughs runs to twenty three volumes. Wake Robin was the first and the following volumes were published regularly with the final two, Under the Maples (1921) and The Last Harvest (1922), being published posthumously by Clara Barrus. Burroughs also published a biography of John James Audubon (1902), Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt (1906), and Bird and Bough (1906).

Shortly before his death, Burroughs suffered from lapses in memory and a decline in heart function. In February 1921, he had an operation to remove an abscess from his chest, after which his health worsened. He died on March 29 1921 on a train near Kingsville, Ohio. He was buried in Roxbury, New York on what would have been his eighty fourth birthday, at the foot of a rock he had termed Boyhood Rock.

I.

NATURE IN ENGLAND

I

The first whiff we got of transatlantic nature was the peaty breath of the peasant chimneys of Ireland while we were yet many miles at sea. What a homelike, fireside smell it was! it seemed to make something long forgotten stir within one. One recognizes it as a characteristic Old World odor, it savors so of the soil and of a ripe and mellow antiquity. I know no other fuel that yields so agreeable a perfume as peat. Unless the Irishman in one has dwindled to a very small fraction, he will be pretty sure to dilate his nostrils and feel some dim awakening of memory on catching the scent of this ancestral fuel. The fat, unctuous peat,the pith and marrow of ages of vegetable growth,how typical it is of much that lies there before us in the elder world; of the slow ripenings and accumulations, of extinct life and forms, decayed civilizations, of ten thousand growths and achievements of the hand and soul of man, now reduced to their last modicum of fertilizing mould!

With the breath of the chimney there came presently the chimney swallow, and dropped much fatigued upon the deck of the steamer. It was a still more welcome and suggestive token,the bird of Virgil and of Theocritus, acquainted with every cottage roof and chimney in Europe, and with the ruined abbeys and castle walls. Except its lighter-colored breast, it seemed identical with our barn swallow; its little black cap appeared pulled down over its eyes in the same manner, and its glossy steel-blue coat, its forked tail, its infantile feet, and its cheerful twitter were the same. But its habits are different; for in Europe this swallow builds in chimneys, and the bird that answers to our chimney swallow, or swift, builds in crevices in barns and houses.

We did not suspect we had taken aboard our pilot in the little swallow, yet so it proved: this light navigator always hails from the port of bright, warm skies; and the next morning we found ourselves sailing between shores basking in full summer sunshine. Those who, after ten days of sorrowing and fasting in the desert of the ocean, have sailed up the Frith of Clyde, and thence up the Clyde to Glasgow, on the morning of a perfect mid-May day, the sky all sunshine, the earth all verdure, know what this experience is; and only those can know it. It takes a good many foul days in Scotland to breed one fair one; but when the fair day does come, it is worth the price paid for it. The soul and sentiment of all fair weather is in it; it is the flowering of the meteorological influences, the rose on this thorn of rain and mist. These fair days, I was told, may be quite confidently looked for in May; we were so fortunate as to experience a series of them, and the day we entered port was such a one as you would select from a hundred.

The traveler is in a mood to be pleased after clearing the Atlantic gulf; the eye in its exuberance is full of caresses and flattery, and the deck of a steamer is a rare vantage-ground on any occasion of sight-seeing; it affords just the isolation and elevation needed. Yet fully discounting these favorable conditions, the fact remains that Scotch sunshine is bewitching, and that the scenery of the Clyde is unequaled by any other approach to Europe. It is Europe, abridged and assorted and passed before you in the space of a few hours,the highlands and lochs and castle-crowned crags on the one hand; and the lowlands, with their parks and farms, their manor halls and matchless verdure, on the other. The eye is conservative, and loves a look of permanence and order, of peace and contentment; and these Scotch shores, with their stone houses, compact masonry, clean fields, grazing herds, ivied walls, massive foliage, perfect roads, verdant mountains, etc., fill all the conditions. We pause an hour in front of Greenock, and then, on the crest of the tide, make our way slowly upward. The landscape closes around us. We can almost hear the cattle ripping off the lush grass in the fields. One feels as if he could eat grass himself. It is pastoral paradise. We can see the daisies and buttercups; and from above a meadow on the right a part of the song of a skylark reaches my ear. Indeed, not a little of the charm and novelty of this part of the voyage was the impression it made as of going afield in an ocean steamer. We had suddenly passed from a wilderness of waters into a verdurous, sunlit landscape, where scarcely any water was visible. The Clyde, soon after you leave Greenock, becomes little more than a large, deep canal, inclosed between meadow banks, and from the deck of the great steamer only the most charming rural sights and sounds greet you. You are at sea amid verdant parks and fields of clover and grain. You behold farm occupationssowing, planting, plowingas from the middle of the Atlantic. Playful heifers and skipping lambs take the place of the leaping dolphins and the basking swordfish. The ship steers her way amid turnip-fields and broad acres of newly planted potatoes. You are not surprised that she needs piloting. A little tug with a rope at her bow pulls her first this way and then that, while one at her stern nudges her right flank and then her left. Presently we come to the ship-building yards of the Clyde, where rural, pastoral scenes are strangely mingled with those of quite another sort. "First a cow and then an iron ship," as one of the voyagers observed. Here a pasture or a meadow, or a field of wheat or oats, and close beside it, without an inch of waste or neutral ground between, rise the skeletons of innumerable ships, like a forest of slender growths of iron, with the workmen hammering amid it like so many noisy woodpeckers. It is doubtful if such a scene can be witnessed anywhere else in the world,an enormous mechanical, commercial, and architectural interest, alternating with the quiet and simplicity of inland farms and home occupations. You could leap from the deck of a half-finished ocean steamer into a field of waving wheat or Winchester beans. These vast shipyards appear to be set down here upon the banks of the Clyde without any interference with the natural surroundings of the place.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Fresh Fields»

Look at similar books to Fresh Fields. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fresh Fields and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.