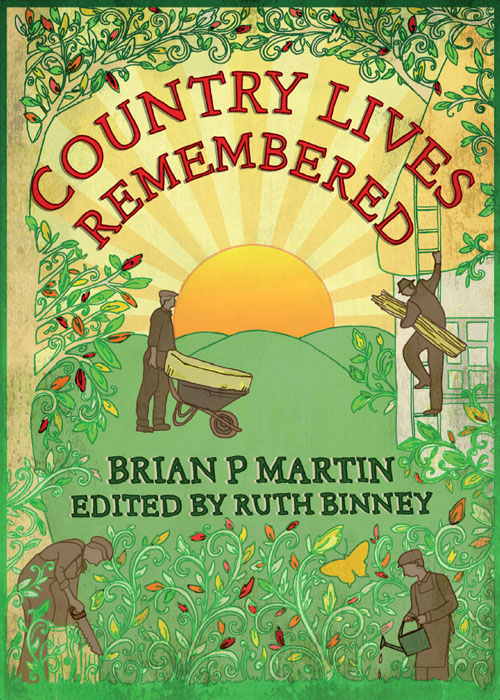

It is, perhaps, an inevitable aspect of human nature that it is only when things we take for granted are threatened with an uncertain future, or even extinction, that we really come to appreciate their true worth. This sentiment has never applied more aptly than in relation to the countryside and the men and women who still work to maintain it and make use of its resources, whether as farmers or coppicers, thatchers or beekeepers, or in dozens of other different ways.

The colourful characters you will meet in this book, whose hard working but so often entertaining lives and memories are described in vivid detail by Brian P Martin, are our link with the countryside of the relatively recent past. They highlight both the intense hardship of previous generations but also the ways in which those close to the land appreciated and worked it with respect and used its resources with care, ever mindful of the need to work with, not against nature. Nearly all have passed away or retired since their stories were first recounted, and you will see that they all experienced huge amounts of change as their lives progressed, but they spring to life from every page as examples of rural trades and occupations that remain vital to the continuance of country traditions.

As the health, well-being and future of our countryside and all it contains are increasingly threatened, so it is ever more vital to look back to the past as through these engrossing biographies and to the needs of the present. Yet while reflecting in such a way it is also encouraging to discover that there is a huge and continuing upsurge of interest in country pursuits and careers. Country crafts are becoming valued in a way that has not been so for a generation, and it is becoming ever easier to enrol for courses in order to train properly for in of these. To help foster this interest, brief details are included for all the occupations included in this book, along with some fascinating reflections on country life in past generations as recorded in the eras before those of the characters featured in these pages.

Anyone who loves the countryside and its people will value these tales and respect the labour of those who dedicated their lives to its service. There is so much to learn from them, not least their practicality, their connection with nature and, of course, their humour.

THE VOICE OF NATURE

Jim Scard, Mole-catcher and Pest Controller

When I drove into the Wiltshire village of Broad Chalke, a few miles south-west of Salisbury, I asked a paper-boy if he knew where Jim Scard lived. With a chuckle, the lad replied: Everyone knows that. His reply was not surprising, for I was seeking a man whom folk of every station had been calling on for decades, seeking his help both for individuals and for the community at large. He is the countrymans countryman, whose great knowledge of rural ways and wildlife is firmly rooted in a lifetimes outdoor employment in many fields. But it is primarily in pest control that this unassuming character has made his mark.

Born in Weymouth, Dorset, on 1 March 1916, Gordon Mortimer Scard (later known to everyone as Jim) never knew his father, a baker who died while Jim was still a toddler. It was his stepfather, an ex-Artillery chap, who pointed him towards a country occupation. His mother was a cook.

The newly united family moved to Lavington, 5 miles south of Devizes, in Wiltshire, when Jim was nine. His earliest memories are of schooldays at Woodford, near Salisbury, which had been his home since he was 4. There were about 120 children at Woodford school every village had a lot of kids because there were many more labourers on the land in those days and almost everyone had a large family.

One of his schoolteachers was a Yorkshireman who was dead keen on cricket. I was only there a week when he gave me a halfpenny for catching him out, but a few days later he caned me with a little willow stick for smoking a broken clay-pipe that someone had thrown away.

But even before he went to school Jim was attracted to the land. He often used to go out with Fred and Bill Bayford, who were carters and ploughmen and just two of 12 men who were employed on the mixed Home Farm. Jim remembers their horses 25-30 lovely animals with great affection. There were two teams so that they could change over at lunchtime, but some men had to take an early lunch to sharpen the cutters. Harvesting was with McCormick and Albion binders and they never started till the dew was off because when the canvasses on the machines got wet the tension was spoiled.

When the horses were set in their furrows, the ploughmen sometimes used to let them walk on a bit while they stopped to shoot starlings with a catapault. I ate one once roasted it over a fire. Never again.

In the summer they used to bring the young horses out. I always remember one which took over two hours to go round the field just once. Every time the old horses went forward he went back. Trouble was the youngsters were easily scared by the banging of the machinery.

One of my earliest memories is of watching em lungeing a horse going round and round a person on a long lead for hours on end to break it in. But the first chore every day was to feed and clean the lot at 6 am.

Wherever you went in the 1920s, horses toiled the long day across every landscape, including the fields of New Farm, on the Blandford road 2 miles from Coombe Bissett, where Jims father worked for Ernie White. One day old White said, Bring young Jim over, so I went on the Saturday to do a bit of hoeing. Youll need something to work with, he said, so he sent me over to Phil the carter, who gave me a muck-scraper. So back I went with it to knock on Whites door and said Will this do?. Buggers, said White. You go back and tell em not to be so silly. But it was all good fun. Everyone had a laugh in those days.

Jim helped his father with the hoeing for 30 bob an acre. This was flat hoeing between the rows. Three weeks later wed clean right round each plant mangolds, swedes, turnips.

When Jim was 12 years old, the family went to live at New Farm. Father got a house there because he was available to the farmer for building work as well as haymaking and other jobs. He was a really good builder I could show you a path now we made 60 years ago, and theres been a few thousand feet over that.

On leaving school at 14, Jim became a labourer on New Farm. He had passed his exams to go on for further education but, like most country folk then, the family simply could not afford it.

In those days you was a real farm labourer and did a bit of everything rolling, harrowing, ploughing and hedge-trimming as well as helping out with the animals. By golly, I really earned my starting wage of 10s, but I did get 3d an hour overtime after fifty hours in a week, working 6 am to 5 pm.

Jim has mixed memories of White. He was a cruel man. One day he went to milk a heifer and she kicked him, so he set about her with a milking stool. He used to put a strap around their legs and then push them till they fell over. After a fright like that all he had to do was tie the strap round their legs again and they wouldnt budge an inch, let alone kick him.