JEWISH ENCOUNTERS

Jonathan Rosen, General Editor

Jewish Encounters is a collaboration between Schocken and Nextbook, a project devoted to the promotion of Jewish literature, culture, and ideas.

>nextbook

PUBLISHED

THE LIFE OF DAVID Robert Pinsky

MAIMONIDES Sherwin B. Nuland

BARNEY ROSS Douglas Century

BETRAYING SPINOZA Rebecca Goldstein

EMMA LAZARUS Esther Schor

THE WICKED SON David Mamet

MARC CHAGALL Jonathan Wilson

JEWS AND POWER Ruth R. Wisse

BENJAMIN DISRAELI Adam Kirsch

RESURRECTING HEBREW Ilan Stavans

THE JEWISH BODY Melvin Konner

RASHI Elie Wiesel

A FINE ROMANCE David Lehman

YEHUDA HALEVI Hillel Halkin

HILLEL Joseph Telushkin

BURNT BOOKS Rodger Kamenetz

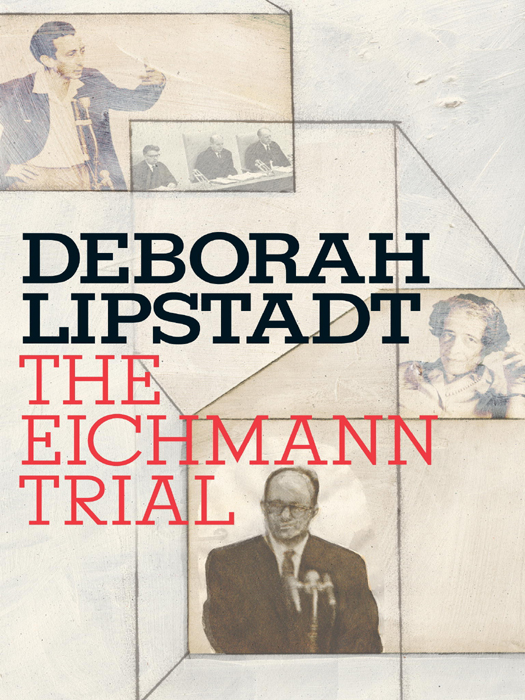

THE EICHMANN TRIAL Deborah E. Lipstadt

FORTHCOMING

THE WORLDS OF SHOLOM ALEICHEM Jeremy Dauber

ABRAHAM Alan M. Dershowitz

MOSES Stephen J. Dubner

BIROBIJAN Masha Gessen

JUDAH MACCABEE Jeffrey Goldberg

SACRED TRASH Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole

THE DAIRY RESTAURANT Ben Katchor

JOB Rabbi Harold S. Kushner

ABRAHAM CAHAN Seth Lipsky

SHOW OF SHOWS David Margolick

MRS. FREUD Daphne Merkin

DAVID BEN-GURION Shimon Peres and David Landau

WHEN GRANT EXPELLED THE JEWS Jonathan Sarna

MESSIANISM Leon Wieseltier

Copyright 2011 by Deborah E. Lipstadt

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lipstadt, Deborah E.

The Eichmann trial / Deborah E. Lipstadt

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-8052-4291-1

1. Eichmann, Adolf, 19061962Trials, litigation, etc.

2. War crime trialsJerusalem 3. Holocaust, Jewish

(19391945) I. Title.

KMK 44. E 33 L 57 2010 345.5694420238dc22 2010028620

www.schocken.com

Jacket illustration by Shannon Freshwater

Jacket images of the Eichmann Trial Government Press

Office, State of Israel; Hannah Arendt from the Jewish

Chronicle Archive / Heritage-Images / Imagestate

Jacket design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

DEDICATION

M uch of the work on this book was done while I was the Judith B. and Burton P. Resnick Invitational Scholar at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. My stay had all the ingredients scholars savor: outstanding colleagues, extensive scholarly resources, and the freedom to do ones own work. Then tragedy struck. At noon June 10, 2009, Special Officer Stephen Tyrone Johns, a long-term guard at the USHMM and a man beloved by the museum staff, saw an elderly man approaching the museum. Eager to be of helpthis was his hallmarkSpecial Officer Johns reached out and pushed open the heavy glass door. Instead of entering, the man, an eighty-eight-year old racist, anti-Semite, and Holocaust denier, raised a rifle from beneath his coat and shot Stephen Tyrone Johns. He was murdered trying to do a kindness. Most mornings, including that day, when I arrived at the museum Special Officer Johns would be there. Often he would kid me about the piles of books I always had in tow. He seemed to have a friendly word for everyone. I had passed his station on my way to give a lecture a few moments before this incident and saw him at the door welcoming people to the museum.

The USHMM reopened two days later. The staff was unsure if people would be too frightened to return. Shortly before the opening, I went outside to see if anyone was there. I fought back the tears when I saw the crowd. The line stretched around the block and down the street. It was significantly longer than for a normal June day. I heard people say that they were there in order to demonstrate that the bigots could not frighten them away. They had come precisely because the shooter wanted to keep them away. Visiting an institution dedicated to teaching about the Holocaust and fighting genocide had become an act of defiance.

It is with deep gratitude and sadness that I dedicate this book to the memory of Special Officer Johns and to the two officers whose quick response prevented this tragedy from assuming far greater proportions. Special Officer Johnss kindness and Special Officers Harry Weekss and Jason Mac McCuistons sheer professionalism are the hallmarks of this institution. We who were there, the thousands of people who visit on a daily basis, and the multitudes who benefit from its myriad of activities owe them and the USHMMs entire staff more than can be imagined. This is a very small token of that gratitude.

Deborah E. Lipstadt

June 10, 2010

Emory University

Atlanta, Georgia

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I n the early 1990s, when serving as a consultant to the team planning the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I attended a meeting of the Content Committee, the group of laypeople who reviewed the plans for the museums permanent exhibition. It promised to be a spirited gathering. At issue was the question of displaying hair that the Germans had harvested from Jewish women at Auschwitz and sold to factories that produced blankets and water-absorbent socks for U-boat crews. When the Soviets liberated the camps, they found storehouses filled with hair. The Auschwitz Museum had given the USHMM a number of kilos of it. The museum designers planned to display it near a pile of victims shoes, which also came from the camps. When the plan was first proposed, some staff members objected, arguing that it degraded and objectified the women. Although it was appropriate to display hair at Auschwitz, they did not think it should be displayed a continent away from there. Some feared that teenagers would find it, given the particular world that this age cohort often inhabits, ghoulishly amusing. Their opposition notwithstanding, the committee voted nine to four to display it. Then a number of survivors grew wary and asked that the matter be reconsidered; hence this meeting. The project director had come equipped with scholarly, psychological, and even rabbinic arguments to counter the opponents. Scholars, including one of the most eminent Holocaust historianscommittee member Raul Hilbergargued that the hair should be displayed because it demonstrated the Final Solutions ultimate rationality. The Germans considered a body part something to be transformed into an industrial object and a salable commodity. Psychologists believed that the display of the hair would be no more disconcerting than many other aspects of the exhibit. Leading Orthodox rabbis determined that displaying it did not constitute a nivul hamet, desecration of the dead, and transgressed no religious rulings. In an attempt to allay some of the objections, the designers proposed that a wall be built in front of the exhibit case. Visitors would have to choose to see the display and not just happen upon it.

But then two committee members, both of whom were survivors, rose. One argued that this would be a violation of feminine identity. A second spoke more personally. That could have been my mothers hair. She never gave you permission to display it. When she sat down she said, in an aside, It could have been