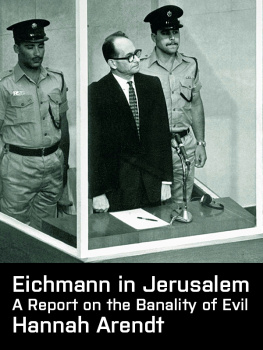

Hannah Arendt - Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

Here you can read online Hannah Arendt - Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: Penguin Classics, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Classics

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Beth Hamishpath the House of Justice: these words shouted by the court usher at the top of his voice make us jump to our feet as they announce the arrival of the three judges, who, bareheaded, in black robes, walk into the courtroom from a side entrance to take their seats on the highest tier of the raised platform, Their long table, soon to be covered with innumerable books and more than fifteen hundred documents, is flanked at each end by the court stenographers. Directly below the judges are the translators, whose services are needed for direct exchanges between the defendant or his counsel and the court; otherwise, the German-speaking accused party, like almost everyone else in the audience, follows the Hebrew proceedings through the simultaneous radio transmission, which is excellent in French, bearable in English, and sheer comedy, frequently incomprehensible, in German. (In view of the scrupulous fairness of all technical arrangements for the trial, it is among the minor mysteries of the new State of Israel that, with its high percentage of German-born people, it was unable to find an adequate translator into the only language the accused and his counsel could understand. For the old prejudice against German Jews, once very pronounced in Israel, is no longer strong enough to account for it. Remains as explication the even older and still very powerful Vitamin P, as the Israelis call protection in government circles and the bureaucracy.) One tier below the translators, facing each other and hence with their profiles turned to the audience, we see the glass booth of the accused and the witness box. Finally, on the bottom tier, with their backs to the audience, are the prosecutor with his staff of four assistant attorneys, and the counsel for the defense, who during the first weeks is accompanied by an assistant.

At no time is there anything theatrical in the conduct of the judges. Their walk is unstudied, their sober and intense attention, visibly stiffening under the impact of grief as they listen to the tales of suffering, is natural; their impatience with the prosecutors attempt to drag out these hearings forever is spontaneous and refreshing, their attitude to the defense perhaps a shade over-polite, as though they had always in mind that Dr. Servatius stood almost alone in this strenuous battle, in an unfamiliar environment, their manner toward the accused always beyond reproach. They are so obviously three good and honest men that one is not surprised that none of them yields to the greatest temptation to playact in this setting that of pretending that they, all three born and educated in Germany, must wait for the Hebrew translation. Moshe Landau, the presiding judge, hardly ever withholds his answer until the translator has done his work, and he frequently interferes in the translation, correcting and improving, evidently grateful for this bit of distraction from an otherwise grim business. Months later, during the cross-examination of the accused, he will even lead his colleagues to use their German mother tongue in the dialogue with Eichmann a proof, if proof were still needed, of his remarkable independence of current public opinion in Israel.

There is no doubt from the very beginning that it is Judge Landau who sets the tone, and that he is doing his best, his very best, to prevent this trial from becoming a show trail under the influence of the prosecutors love of showmanship. Among the reasons he cannot always succeed is the simple fact that the proceedings happen on a stage before an audience, with the ushers marvelous shout at the beginning of each session producing the effect of the rising curtain. Whoever planned this auditorium in the newly built Beth Haam, the House of the People (now surrounded by high fences, guarded from roof to cellar by heavily armed police, and with a row of wooden barracks in the front courtyard in which all comers arc expertly frisked), had a theater in mind, complete with orchestra and gallery, with proscenium and stage, and with side doors for the actors entrance. Clearly, this courtroom is not a bad place for the show trial David Ben-Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel, had in mind when he decided to have Eichmann kidnaped in Argentina and brought to the District Court of Jerusalem to stand trial for his role in the final solution of the Jewish question. And Ben-Gurion, rightly called the architect of the state, remains the invisible stage manager of the proceedings. Not once does he attend a session; in the courtroom he speaks with the voice of Gideon Hausner, the Attorney General, who, representing the government, does his best, his very best, to obey his master. And if, fortunately, his best often turns out not to be good enough, the reason is that the trial is presided over by someone who serves Justice as faithfully as Mr. Hausner serves the State of Israel. Justice demands that the accused be prosecuted, defended, and judged, and that all the other questions of seemingly greater import of How could it happen? and Why did it happen?, of Why the Jews? and Why the Germans?, of What was the role of other nations? and What was the extent of coresponsibility on the side of the Allies?, of How could the Jews through their own leaders cooperate in their own destruction? and Why did they go to their death like lambs to the slaughter? be left in abeyance. Justice insists on the importance of Adolf Eichmann, son of Karl Adolf Eichmann, the man in the glass booth built for his protection: medium-sized, slender, middle-aged, with receding hair, ill-fitting teeth, and nearsighted eyes, who throughout the trial keeps craning his scraggy neck toward the bench (not once does he face the audience), and who desperately and for the most part successfully maintains his self-control despite the nervous tic to which his mouth must have become subject long before this trial started. On trial are his deeds, not the sufferings of the Jews, not the German people or mankind, not even anti-Semitism and racism.

And Justice, though perhaps an abstraction for those of Mr. Ben-Gurions turn of mind, proves to be a much sterner master than the Prime Minister with all his power. The latters rule, as Mr. Hausner is not slow in demonstrating, is permissive; it permits the prosecutor to give press-conferences and interviews for television during the trial (the American program, sponsored by the Glickman Corporation, is constantly interrupted business as usual by real-estate advertising), and even spontaneous outbursts to reporters in the court building he is sick of cross-examining Eichmann, who answers all questions with lies; it permits frequent side glances into the audience, and the theatrics characteristic of a more than ordinary vanity, which finally achieves its triumph in the White House with a compliment on a job well done by the President of the United States. Justice does not permit anything of the sort; it demands seclusion, it permits sorrow rather than anger, and it prescribes the most careful abstention from all the nice pleasures of putting oneself in the limelight. Judge Landaus visit to this country shortly after the trial was not publicized, except among the Jewish organizations for which it was undertaken.

Yet no matter how consistently the judges shunned the limelight, there they were, seated at the top of the raised platform, facing the audience as from the stage in a play. The audience was supposed to represent the whole world, and in the first few weeks it indeed consisted chiefly of newspapermen and magazine writers who had flocked to Jerusalem from the four corners of the earth. They were to watch a spectacle as sensational as the Nuremberg Trials, only this time the tragedy of Jewry as a whole was to be the central concern. For if we shall charge [Eichmann] also with crimes against non-Jews, this is not because he committed them, but, surprisingly, because we make no ethnic distinctions. Certainly a remarkable sentence for a prosecutor to utter in his opening speech; it proved to be the key sentence in the case for the prosecution. For this case was` built on what the Jews had suffered, not on what Eichmann had done. And, according to Mr. Hausner, this distinction would be immaterial, because there was only one man who had been concerned almost entirely with the Jews, whose business had been their destruction, whose role in the establishment of the iniquitous regime had been limited to them. That was Adolf Eichmann. Was it not logical to bring before the court all the facts of Jewish suffering (which, of course, were never in dispute) and then look for evidence which in one way or another would connect Eichmann with what had happened? The Nuremberg Trials, where the defendants had been indicted for crimes against the members of various nations, had left the Jewish tragedy out of account for the simple reason that Eichmann had not been there.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil»

Look at similar books to Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.