INTRODUCTION

BY JEROME KOHN

Particular questions must receive particular answers; and if the series of crises in which we have lived since the beginning of the century can teach us anything at all, it is, I think, the simple fact that there are no general standards to determine our judgments unfailingly, no general rules under which to subsume the particular cases with any degree of certainty. With these words Hannah Arendt (190675) encapsulated what throughout her life she regarded as the problematic nature of the relation of philosophy to politics, or of theory to practice, or, more simply and precisely, of thinking to acting. At the time she was addressing a large audience that had gathered from across the nation in Manhattan's Riverside Church to attend a colloquium on The Crisis Character of Modern Society.morally wrong, they turned to Arendt and the other speakers whose experience of past crises would, they hoped, shed light on the present one.

At least with Arendt they were in for something of a disappointment. Despite the fact that totalitarianism and other crises of the twentieth century had been the focus of her thought for many years, she offered them no general standards to measure the wrong that had been done, much less any general rules to apply to the wrong that was now being done. She said nothing to substantiate the convictions they already held, or to render their opinions more convincing to others, or to make their antiwar efforts more effective. Arendt did not believe that analogies derived retrospectively from what had or had not worked in the past would avert the pitfalls of the present situation. As she saw it, the spontaneity of political action is yoked to the contingency of its specific conditions, which renders such analogies unavailing. That appeasement had failed in Munich in 1938, for instance, did not entail that negotiations were pointless in 1966. And while Arendt believed that the entire world, for its own sake, must remain vigilant in resisting such elements as racism and global expansionism which had crystallized in totalitarianism, she objected to the indiscriminate, analogizing application of the term totalitarian to whatever regime the United States might oppose.

Arendt did not mean that the past as such was irrelevantshe never tired of repeating William Faulkner's epigram The past is never dead, it's not even pastbut that applying so-called lessons of history to indicate what the future holds in store is only slightly more useful than examining entrails or reading tea leaves. In other words, her view of the past, clearly stated in Home to Roost, the last piece included in Responsibility and Judgment, was more complicated and less confident than that contained in Santayana's frequently repeated remark, Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. On the contrary, Arendt believed that for better or worse our world has become what in reality it is: the world we live in at any given moment is the world of the past. Her belief is hardly a historical lesson, and it raises the question of how the pastpast actioncan be experienced in the present. In Home to Roost she did not answer that question with a theory, but her bittersweet judgment of the state of the Republic in 1975 provided an example of what she meant by the presence of the past. Although its beginnings two hundred years ago were glorious, she said, the betrayal of America's institutions of liberty haunts us today. The facts have come home to roost, and the only way we can remain true to our origins is not by blaming scapegoats, or by escaping into images, theories, or sheer follies, but by trying to make those facts welcome. It is we as a people who are responsible for them now.

The sole advice, if it can be called that, she ever offered was embedded in the particular answers she gave to particular questions, which the following anecdote may illustrate. Arendt's response was a judgment of a particular situation in its particularity, which the many words of argumentation had obscured.

No one was more aware than Arendt that the political crises of the twentieth centuryfirst the outbreak of total war in 1914; then the rise of totalitarian regimes in Russia and Germany and their annihilation of entire classes and races of human beings; then the invention of the atomic bomb and its deployment to obliterate two Japanese cities in World War II; then the cold war and the unprecedented capacity of the post-totalitarian world to destroy itself with nuclear weapons; then Korea; then Vietnam; and on and on, events cascading like a Niagara Falls of historycan be viewed in terms of a breakdown in morality. That there had been such a collapse was obvious. But the controversial, challenging, and difficult heart of what Arendt came to see was that the moral breakdown was not due to the ignorance or wickedness of men who failed to recognize moral truths, but rather to the inadequacy of moral truths as standards to judge what men had become capable of doing. The only general conclusion that Arendt allowed herself pointed, ironically, to the generality of the sweeping change in what the long tradition of Western thought had held sacrosanct. The tradition of moral thought had been broken, not by philosophical ideas but by the political facts of the twentieth century and could not be put back together again.

Arendt was neither a nihilist nor an amoralist, but a thinker who followed where her thinking led. Following her, however, imposes a task on her readersnot so much on their intelligence or knowledge as on their ability to think. It is not theoretical solutions she advances but an abundance of incentives to think for oneself. She found immensely significant Tocqueville's insight that when in times of crisis or genuine turning points the past has ceased to throw its light upon the future, the mind of man wanders in obscurity. At such moments (and to her the present was such a moment), she found the mind's obscurity to be the clearest indication of the need to consider anew the meaning of human responsibility and the power of human judgment.

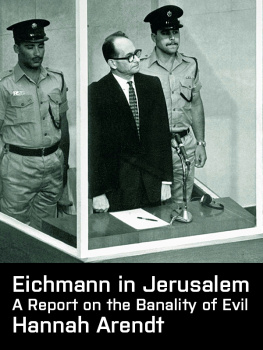

In 1966 Hannah Arendt was famous, which is not to gainsay that to some her fame appeared as infamy. Three years earlier, in 1963, the publication of her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil created a storm of controversy that wrecked a number of close friendships and alienated her from almost the entire Jewish community worldwide. This was grievous to Arendt, who was born a German Jew, a fact she considered a given of her existence, a gift of a specific kind of experience that proved crucial in the development of her thought. To give a single example: When one is attacked as a Jew, Arendt found it necessary to respond as a Jew. To respond in the name of humanity, claiming the Rights of Man, was absurdly beside the point, the denial but not the refutation of the accusation that Jews