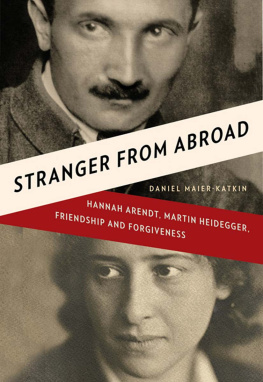

STRANGER FROM ABROAD

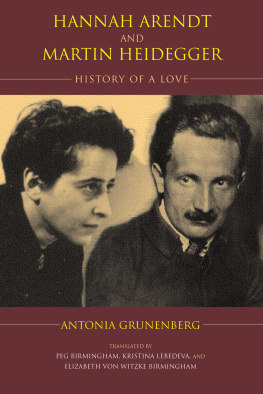

Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness

D ANIEL M AIER -K ATKIN

W. W. N ORTON & C OMPANY

N EW Y ORK L ONDON

Copyright 2010 by Daniel Maier-Katkin

All rights reserved

Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, Credits constitute an extension of the copyright page.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Maier-Katkin, Daniel, 1945

Stranger from abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, friendship, and forgiveness / Daniel Maier-Katkin.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07731-5

1. Arendt, Hannah, 19061975Friends and associates. 2. Heidegger, Martin, 18891976Friends and associates. I. Title.

B945.A694M35 2010

320.5092dc22

[B]

2009043992

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To the memory of my parents,

who brought me into one world,

and to Birgit,

who showed me another

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to my children, Andrew, Rebecca, Rosalia and Hannah, for their support and encouragement during long years when I must have seemed too often preoccupied with Hannah Arendt. Rebecca was among the most thorough and thoughtful of my readers and Hannah was always happy to discuss whatever I was working on, especially on our long morning drives to the Magnolia School. Other readers for whose helpful suggestions I am grateful include Maria Foscarinis, Nathan Stoltzfus, Elliott Currie, Bill Cloonan, Neil Jumonville, Martin Kavka, Karl Sabbagh, Mary Delina Wright, Peter Fleming, John Davis, Edward Katkin, Sylvia Katkin, and Caryn Pally. Sumner Twiss, my colleague at the Center for the Advancement of Human Rights, has been invaluable as a source of ideas and references.

Conversations with Jerome Kohn, when I was just beginning to think that the story of Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger had never been properly told, helped to shape my thinking. I am indebted to Bert Lockwood, editor of Human Rights Quarterly , and Christina Thompson, editor of the Harvard Review , who both saw the value of this project early on; without their decisions to publish early versions of the story the book might never have come to fruition. Dan OConnell also saw the value of the project early on. His support and advice were immensely helpful to me.

My tough, challenging, and gifted editor, Alane Mason, taught me how to turn a story into a book and never stopped demanding additional detail, clearer thinking, and better, more precise, and more elegant use of language. I should add too how impressed I have been by the kindness and competence of the people who work with her at W. W. Norton.

I also want to acknowledge several friends, Bruce and Lisa Bullington, Ray and Nonnie Fleming, Frank Kron, Alex Wender, Teddy Tollet, Diop Kamau, and Lorenz Bllinger, from whom I have learned a great deal over many years about people and the diversity of cultures. Their influence on my way of thinking about human relationships is reflected between the lines and in the fundamental conception of the story I have tried to tell.

Then there is Birgit, my beloved life companion and guide to all things European and to scholarship in the humanities. Without Birgit there would never have been the germ of the idea that has culminated in Stranger from Abroad nor the will or skill to write it.

Much of what has been written in the past about the relationship between Arendt and Heidegger is the work of their detractors. Arendt was judgmental and controversial, and her youthful love affair and subsequent reconciliation with Heidegger have been used to throw some of her critical judgments into doubt. I have tried to tell their story differently, more accurately and with greater sensitivity to the complexity of their thinking and feelings. If I have not succeeded, the responsibility, despite all the help I have acknowledged here, is mine alone.

STRANGER FROM ABROAD

T O SAY THAT A THING ENDURES, Hannah Arendt wrote to Martin Heidegger around the time of her sixtieth birthday, means that there is something in the end that is the same as it was in the beginning. The something she had in mind was an aspect of their relationshiptheir lovethat had changed but endured despite everything that happened between them and to Germans and Jews in the twentieth century.

As thinkers, both professionally and by temperament, Arendt and Heidegger were attentive to beginnings and ends. He celebrated the power and radiance of beginnings, but experienced them as distant and cooling explosions like creation itself or the Greek invention of philosophy. His thought was drawn to the brevity of each individuals existence and the infinite nothingness that surrounded it. Nevertheless, at the center of Heideggers thought is the meaning of being, which every person must establish for him or herself.

Familiarity with ends came early for Hannah; her father and grandfather both died the year that she was seven. Fear of death cast shadows across her early life, but these faded or came under

It was central to her thought that beginnings, which are by definition unprecedented and which cannot be predicted, are the wellspring of human spontaneity and freedom. Equally central was pluralism: the observation that the world into which every individual is born is shared with others. The world is already in motion when we arrive, and it is only by joining the dance that we become ourselves.

Hannahs own beginning was an insertion into the world of Germans and Jews in Hanover in 1906, barely twenty-five years before the Nazi rise to power, at a time when there was not yet any harbinger of impending disaster. The circumstances of Jews in Germany were as good as they ever had been anywhere in the Diaspora. In the second half of the nineteenth century, enlightenment and emancipation had opened the gates to the ghetto, and ushered in an age of tolerance. While anti-Semitism and dislike and distrust of Jews persisted in some corners of society, legal barriers to full participation were abolished and German Jews had established themselves in the realms of commerce, banking, the arts, sciences, and learned professions. Conversions to Christianity and interfaith marriages were common, reflecting not only the desire of Jews to fit into the dominant culture, but also the openness with which they were received.

When Hannah was still very young, her family moved to Knigsberg, where her parents had been born and where their parents were established, respected members of the community. Knigsberg, the capital of East Prussia, was a remote, well-fortified, but nonetheless cosmopolitan Baltic seaport and university city that had been the capital of German enlightenment in the nineteenth century during the lifetime of Immanuel Kant. Forty years before her birth Knigsberg would not have been a place (if indeed there had been any such place) where a young Jewish woman could have been educated in Latin, Greek, the classics, or philosophy. Forty years after her birth the city, cleansed of all its Jews, lay in ruins. Hannahs opportunities, like everyone elses, depended upon the accident of birth.

Knigsberg, an ancient harbor town on the Baltic, its streets lined with narrow four-story timbered brick and stucco buildings under ornate Rococo roofs, had been a center of trade since the Hanseatic League and was still a vital residential and commercial quarter in Hannahs childhood. The old city, paved with wide cobblestone boulevards and commodious squares, extended inland from the hub of government and commerce surrounding a Gothic Teutonic castle. Further up the river Pregel, the modern city, where the Arendts lived, contained more spacious estates along canals and tributaries. Knigsberg was of the water almost as much as it was of the land; and many buildings, including the ornate Moorish-style synagogue, had back entrances along a dock or quay, as in Venice or Amsterdam.