Grunenberg Antonia - Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger

Here you can read online Grunenberg Antonia - Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Indiana University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger

- Author:

- Publisher:Indiana University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

HANNAH ARENDT AND MARTIN HEIDEGGER

STUDIES IN CONTINENTAL THOUGHT

John Sallis, editor

Consulting Editors

Robert Bernasconi

John D. Caputo

David Carr

Edward S. Casey

David Farrell Krell

Lenore Langsdorf

James Risser

Dennis J. Schmidt

Calvin O. Schrag

Charles E. Scott

Daniela Vallega-Neu

David Wood

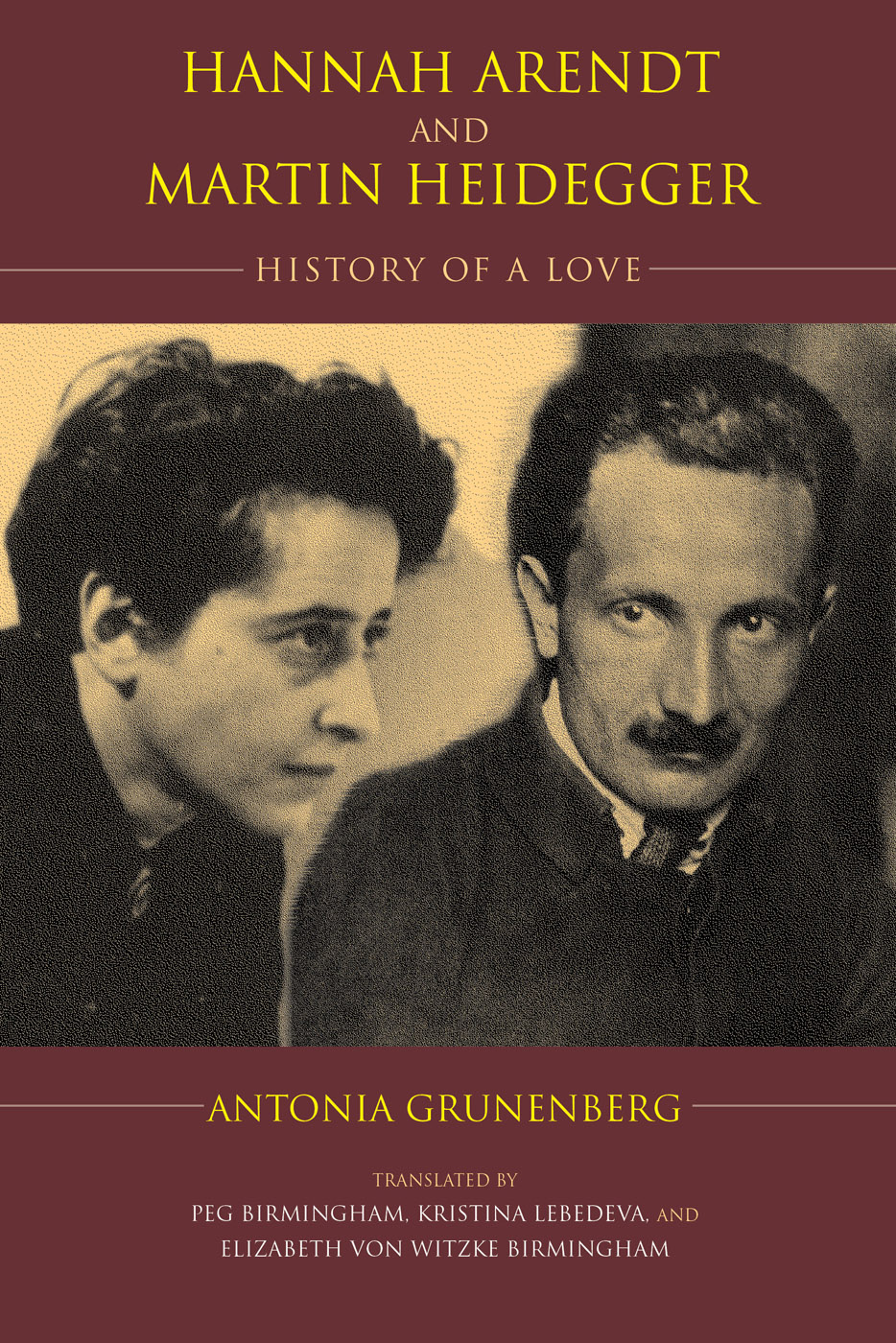

HANNAH ARENDT AND MARTIN HEIDEGGER

History of a Love

Antonia Grunenberg

Translated by Peg Birmingham, Kristina Lebedeva, and Elizabeth von Witzke Birmingham

Indiana University Press

Bloomington and Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Published in German as Hannah Arendt und Martin Heidegger: Geschichte einer Liebe.

2006 by Piper Verlag GmbH, Mnchen.

English translation 2017 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02523-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02537-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-02718-4 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 522 21 20 19 18 17

Contents

by Peg Birmingham

illustrations begin on

Foreword

Arendt and Heidegger: Erotic Reversals, Conflict, and Fissures

Peg Birmingham

O VER THE PAST several decades the question has often been raised: How could Hannah Arendt have reconciled with Martin Heidegger, whom she knew had joined and actively participated in the Nazi Party when taking over the rectorship of Freiburg University? The same question, asked differently: How could Arendt, a Jewish-German refugee who had fled Germany in 1931, have resumed her relationship with Heidegger, her former teacher, on her first trip back to Germany in 1948, a trip undertaken on behalf of the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction to recover stolen Jewish cultural artifacts? Grunenbergs biography is remarkable in showing that this way of asking the question is too stark and does not capture the ways in which the history of these two major thinkers of the twentieth century is not simply one of a broken intimacy followed by reconciliation; instead, it is a history marked as much by estrangement, breaks, and distance as it is of proximity, reunion, and resumed friendship. The biography reveals that the history of the love between Arendt and Heidegger is best captured in the English idiom they have a history, indicating an erotic relationship that is complicated and fraught.

Perhaps the most striking example of the estrangement, distance, and reversals that continued to mark the history between Arendt and Heidegger is the long silence between them that ensued only a few years after the reconciliation in 1948, a silence due not to political or philosophical disagreementson the contrary, it was personal. The personal silence finds momentary philosophical voice in a note that Arendt sent to Heidegger via her publisher on the occasion of the 1960 publication of Vita Activa, the German edition of The Human Condition: You will see that the book does not contain a dedication. Had things worked out properly between usand I mean between, that is, neither you nor meI would have asked you if I might dedicate it to you; it came directly out of the first Freiburg days and hence owes practically everything to you in every respect. As the note indicates, this lack of dedication and of response is due to the absence of a personal between that renders impossible any philosophical engagement between them. More than a decade later in 1971 there is yet another reversal as Arendt dedicates Life of the Mind: Thinking to Heidegger, a dedication that cites several lines from his Discourse on Thinking. By this time, another between has been established.

As Grunenberg notes, the history between Arendt and Heidegger, a history spanning fifty-one years, takes place against the background of the twentieth century with its violence, catastrophes, wars, and mass migrations. Here, too, Grunenberg adds significantly to Elizabeth Young-Bruehls biography. She capturesas perhaps only someone who was born during the Dresden firebombing in 1945, who spent her early childhood in East Germany, who then escaped with her family to West Germany, and who as a Berliner participated in the 1989 reunificationthe ways in which Arendt lived in two worlds, the European and the American, unwilling and unable to decide between the two. In fact, Grunenbergs biography emphasizes the ways in which Arendt continued to be an exile even after receiving her citizenship papers in 1948. Better, she captures the ways in which Arendt lived a transnational existence after 1941 and how this transnational existence influenced her thinking. Arendts fragmented history, her critique of history as process, her critique of the nation-state and a certain conception of human rights and citizenship emerge first from her status as a refugee and then as a nationalized US citizen who never cut ties to Europe generally and to Germany specifically. This experience of exile appears to mark the greatest distance between Arendt and Heidegger, the latter living his entire life in Germany and for much of that life in one city: Freiburg.

Yet here, too, caution must be exercised as Grunenbergs biography shows how Heideggers world, both personally and professionally, collapsed after the Second World War. Her history of the relationship between these two thinkers raises the difficult question of the difference between a collapsed world and a world of exile and how this difference led Heidegger and Arendt to different understandings of a new beginning, a central concern that runs through each of their work.

Grunenbergs biography of these two thinkers stands between Elzbieta Ettingers pinched biography of Arendt and Heidegger, in which Arendt is reduced to nothing more than a disciple of Heidegger, and Elizabeth Young-Bruehls biography of Arendt, in which her relation to Heidegger is briefly discussed. Grunenberg does not reduce Arendt to Heideggers disciple nor is she interested in adding to Young-Bruehls account by claiming that Heidegger is more central to Arendts life than Young-Breuhl admits. Instead, Grunenbergs notable achievement is to show how Arendt and Heideggers shared history, from their initial meeting in Heideggers 1924 seminar on Platos Sophist, is the history of a double, inseparable eros: the philosophical and the personal. (At the same time she documents the ways in which this double eros of the philosophical and the personal infuses each thinkers relation with others.) This is not to reduce the work of each thinker to his or her biography or even to a shared biography. Grunenberg is not arguing that Arendts thinking can be read solely through the lens of Heideggers thought. It cannot. As she writes in her preface to the English translation, there are significant differences between Arendts and Heideggers thought. Nor is she arguing that Heidegger was influenced by Arendts insistence on the philosophical importance of the

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger»

Look at similar books to Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.