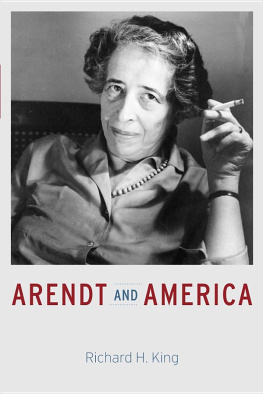

Richard H. King

Richard H. King is professor emeritus of U.S. intellectual history at the University of Nottingham, UK. He is the editor of Obama and Race: History, Culture, Politics, coeditor of Hannah Arendt and the Uses of History: Imperialism, Race, Nation, Genocide, and the author of Race, Culture, and the Intellectuals, 19401970, among other books.

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

King, Richard H., author.

Arendt and America / Richard H. King.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-31149-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-31152-4 (e-book) 1. Arendt, Hannah, 19061975. 2. United StatesHistory20th century. 3. Political scientistsUnites StatesBiography. I. Title.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Hannah Arendts World

Certainly Arendt herself believed that there was something differentand politically liberatingabout the American political culture, particularly the achievement of the Framers. Jonas aptly captured it with the phrase the idea of the Republic.

If the Republic was the great American experience that Arendt responded the promise of American life in general and is hardly confined to immigrants and newcomers.

As a place of new beginnings, America was also a symbol of modernity. Arendts friend, the art critic Harold Rosenberg, named a group of postwar American artists action painters and saw them as representatives of the tradition of the new. The parallels with Arendts concerns are striking. But

Indeed, as the Vietnam and Watergate crises

Thinking in, Thinking about America

In this introduction, I want to sketch in how Arendt came to America in 1941, halfway through her life, and what she brought with her by way of intellectual and cultural equipment. This will also involve a look at her early thinking about the nature of her adopted country, as compared with predecessors such as Max Weber and Alexis de Tocqueville. After discussing her position among the New York intellectuals in the postwar/Cold War world, I will conclude by offering some generalizations about her style of thought and then provide a chapter-by-chapter outline.

I begin with the assumption that Arendts life and thought were contribution to American intellectual history and political thought was an American version of republicanism; her great worry was that this republic would be lost.

Perhaps this is why Arendts engagement with America does not fit very comfortably with somewhat similar examples in trans-Atlantic intellectual history. Unlike Friedrich Nietzsche or Martin Heidegger, she actually came to America

Let me be clear. Arendts complex relationship to America isnt the only important thing about her thought. But that body of thought only makes full sense when her relationship to America, in her life and thought, is taken into account. Put most strongly, the United States was not just where she lived and where her thought was first published. It was a crucial theme and concern of her thought. This means that I have stressed Arendts interaction with American intellectuals, with American thought and culture, and with America as a place and set of institutions rather than treat her life and thought as detached from where she actually lived, as though the life of the mind was lived no place particularly. She taught her American contemporaries, friend and foe, a good deal but she also learned from them. She was concerned, as a political thinker, with the origins of American political thought and institutions. Above all, as a citizen, she was concerned about the survival of the American republic.

Arendt as Refugee

All that said, the interaction between Hannah Arendts own sense of self and where she lived was a complex one. In coming to America, she had lost her home and countryas had millions of other Europeans.

The semantics of the migr experience are tricky. Clearly Arendt was in exile in America, but hers was the voice of a refugee and not a survivor, claims Gabriel Motzkin. Having fled Germany in 1933she was jailed eight days by the Gestapo for illegal research work and also aiding fleeing radicalsArendt fled to Paris (via Prague and Geneva), where

With all this, it is hardly surprising that statelessness as a legal status Martha Arendt, and she was more deeply involved than most migr intellectuals in the political, intellectual, and cultural life of America in her time. But hers was not exactly an American life. How could it have been otherwise?

Once in New York, she set about learning English (she and Walter Benjamin had begun studying it together in Paris). She gradually made contacts and became part her political thought.

Not surprisingly, Arendt missed the philosophical culture of pre-Nazi Germany. As she explained, with a note of exasperation, to Karl Jaspers: Sometimes I wonder which is more difficultto impart to Germans some sense of politics or to give America a light dusting of philosophy. anti-intellectualism, even though she admired, as noted, the American intellectuals she had met.

Arendt also seemed less interested in America the place and the experience than was either Alexis de Tocqueville or Max Weber, both of whom traveled extensively and enthusiastically around the United States in the time they spent there. From when they arrived in 1941, Arendt and her husband

Nor did she ever really propose a comprehensive overview of the American experience to match Alexis de Tocquevilles Democracy in America. Max Weber was most interested in social and the economic matters, as shaped by religious ideas and institutions, precisely

Seyla Benhabibs description of her as a reluctant modernist captures something essential about her position. public good.

Never a defender of capitalism, Arendt was more concerned with the political realm than with either the social or the cultural realms. The neo-Marxist Frankfurt School saw America as the homeland of advanced capitalism

Overall, Arendt lacked what Germans call Fingerspitzengefhl (or an intuitive feeling) for Americas deceptively complex culture, though she occasionally Neither Leo Strauss (or most of his followers) nor the Frankfurter theorists ever grappled with the American race question in the way that Arendt did.

Nor, having arrived in America after the Depression, did Arendt ever have much sense of the flowering of American

Of those who have written about Arendt, only George Kateb has tried to go below the surface of her in a rejection of politics altogether.

It is undeniable that Arendt was put off by some of what Kateb identified. Philosophically, nature was far from being a standard of value or worth, since her commitment was to the world of meaning, the human artifice. Her reading of Herman Melvilles Billy Budd assumed that Budd, a child of nature, was destined to act in ways destructive of the human

But if wildness is associated with a democratic ethos, Arendts suggest an attraction to the radical, even nihilistic, streak in American literature. From this point of view, it may have been pragmatisms failure to grapple with the modern problem of nihilism that explains her indifference toward it. Or perhaps she had had more than her fill of the intellectualized violence that totalitarian intellectuals in Europe were fond of apotheosizing.