This book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon foundation.

Copyright 2014 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

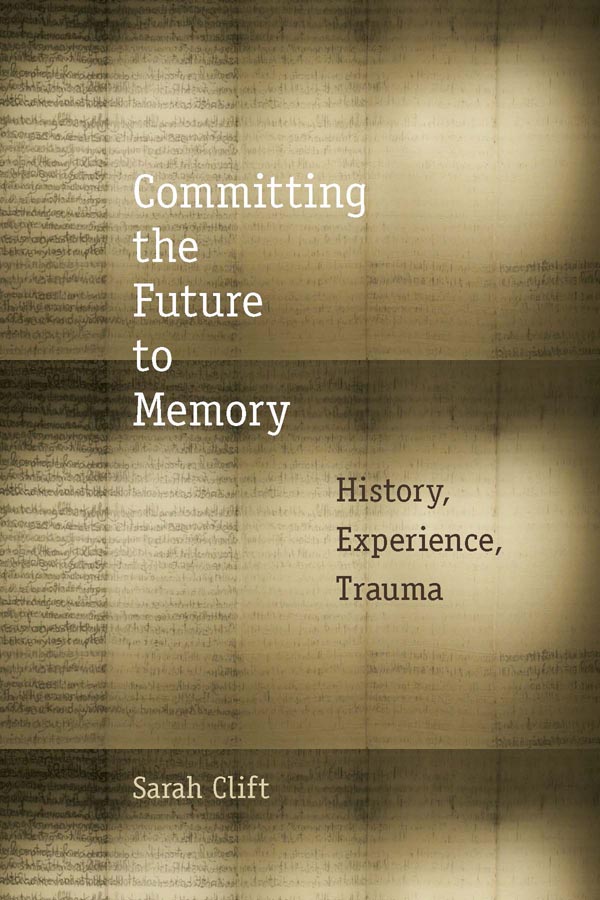

Clift, Sarah.

Committing the future to memory : history, experience, trauma / Sarah Clift. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8232-5420-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8232-5421-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. HistoriographyPhilosophy. 2. Civilization, ModernPhilosophy. 3. Benjamin, Walter, 18921940. 4. Arendt, Hannah, 19061975. 5. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 17701831. 6. Locke, John, 16321704. 7. Blanchot, Maurice. I. Title.

D13.C5838 2014

907.2dc23

2013015192

First edition

Contents

I am very glad for the chance to express my gratitude to the many people who helped me in this work, without whom its completion would have remained an insurmountable problem (to use Maurice Blanchots apt phrase). First and foremost, I would like to thank Ian Balfour, Howard Adelman, and Stephen Levine for their unwavering support, critical acuity, and seemingly endless patience. In addition to their support of this project in its earliest stages, they have offered me enduring models of intellectual generosity and rigor. A great many other colleagues and friends supported me in various ways, whether by reading portions of the work, suggesting resources, offering critiques, editing, catching mistakes, minding me, giving me a quiet room and uninterrupted time to work, nudging my thinking further, putting up with my intellectual obsessions, or offering much needed diversions. They include Mark Webber, Cathy Caruth, Michelle Cohen, Cory Stockwell, Rebecca Comay, Deborah Britzman, Scott Marratto, David Levine, Karen Valihora, Kir Kuiken, Ian Stewart, Dorota Glowacka, Alexandra Morrison, Doug Freake, Jonathan Bordo, Susan Dodd, Thomas Trezise, Rebecca Wittmann, Jean-Luc Nancy, John Zilkosky, Daniel Brandes, Aleida Assmann, Paul Antze, Gerald Butts, and Zsuzsa Baross. I would also like to extend my warmest thanks to the fantastic students in my upper-year seminar class on The Concept of Memory in Late Modernity at the University of Kings College in Halifax. Their engagement with all things memorial over the past few years has been a huge inspiration for me and, above all, a powerful reminder of the point of it all.

Thanks are also due to the organizations and funding bodies that made possible my research and its dissemination: the Joseph Webber Memorial Scholarship, the OntarioBaden-Wrttemberg exchange scholarship, the Freie Universitt (Berlin) scholarship fund, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship fund, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The University of Kings College in Halifax provided a stimulating atmosphere within which I could bring this project to completion.

Finally, this book owes most of all to those who lived with it and saw the project through to the end with kindness, joy, and loveto Sherrill and Gerald Clift, Alison Clift, Uli vom Hagen, and above all to Tovah, who came along and changed everything.

In the preface to the second edition of the Science of Logic, Hegel refers to the peculiar restlessness and distraction of our modern consciousness. Finally, for Hegel, this restlessness is the active dimension without which there would be no movement, no change, only stasis, and finally the sickness that leads to wholesale alienation and despair.

Despite the fact that the Phenomenology of Spirit famously and notoriously ends with a difficult scene of memory, Hegel could not have predicted the extent to which his notion of restlessness would become so concretely manifest in a world saturated with memory. But indeed, the political, ethical, and epistemological questions regarding how we remember have become some of the most important, and some of the most disquieted, questions of our time. The demonstrable rise of secular practices of historical memory attests to this disquiet, as do the proliferation of theoretical attempts to understand the significance of this phenomenon.

As the diversity of the viewpoints presented in scholarship on memory attests, it is difficult to know exactly how to interpret this phenomenonhow to judge its social and cultural meanings, how to situate its explanation, or how to historicize its occurrence. But its presence is nonetheless palpable. As Jan Assmannan Egyptologist by training whose work has led him to investigate the contemporary phenomenon of cultural memorybaldly states in the opening lines of Das kulturelle Gedchtnis (1992): For some years now, we have been experiencing a virulence of memory.

To describe memory in terms of virulence is, I think, a provocative gesture, suggesting as it does that memory operates under the sign of a condition whose power to reproduce itself lies in its ubiquity, its trajectory largely unknown, and reference to its origin circuitous and difficult. If memory has indeed long functioned as a synthesis or historical link between the past and the present, in our day it has also come to name a kind of reproductive dilemma and, by extension, a dilemma of representation. Committing the Future to Memory arises out of the conviction that there remains a great deal to be clarified regarding this virulence of historical memory, in its political and ethical dimensions, but also in relation to its media, to its social functions, and to the experiences of time that emerge out of it.

The general increase of the significance of historical memory in the public sphere suggests that there is widespread agreement, albeit perhaps a tacit one, on the limited social value of academic historical knowledge. While historical research and scholarship continue to provide important frameworks for the awareness of what happens in history and, to a lesser extent, while they also contribute to theoretical questions of historical methodology, they do not, for all that, provide the context for a greater understanding of the relation between the past and the present nor, for that matter, do they provide a clarification of what the implications of such an understanding might be.

The current engagement with memory suggests, then, not only that historical knowledge confronts its own limit in its inability to produce a subject who understands the past, but also that the rubric of historical memory is better suited to perform this role; it offers a more powerful and a more critical register in which to articulate the disasters that constitute the political origins of many contemporary collective and individual identities. This new importance of historical memory in the political sphere means that the ethos of Never Forget is neither tranquil recollection nor memorial celebration (as it is, for instance, in Hannah Arendts assessment of ancient Greek memory) nor is it simply a recalling of the past, for the sake of posterity or national consolidation. The knell that it sounds today is one of traumatic reminder, of warning, of threat: The injunction of Never Forget has become virtually indiscernible from the future-oriented promise of Never Again. Memory has thus been given the task of creating a better future by virtue of past events that