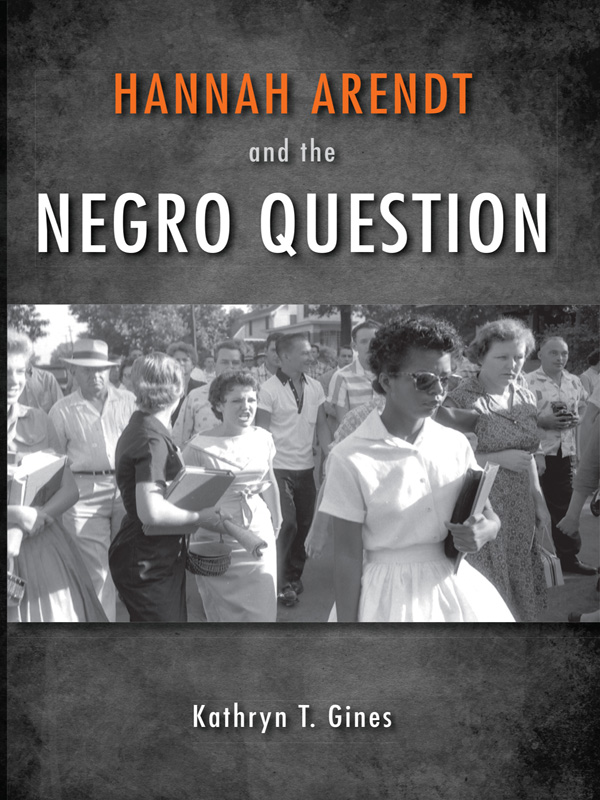

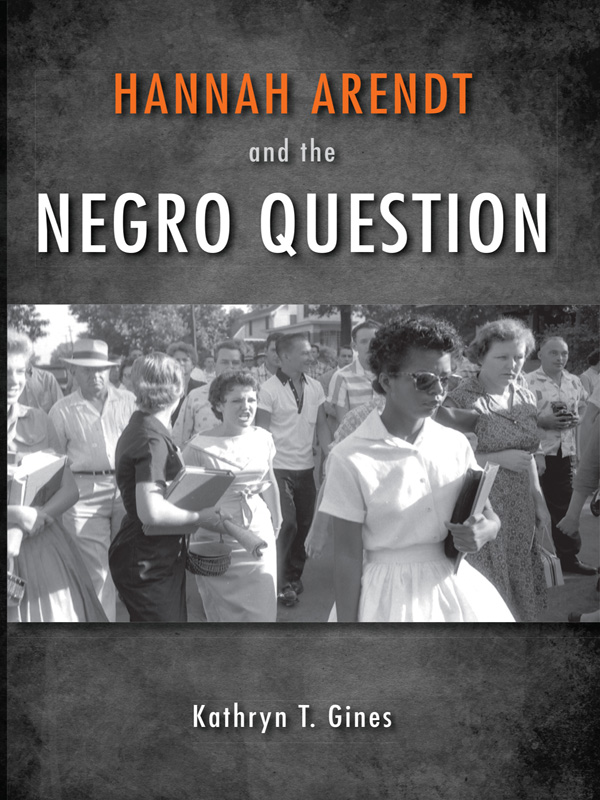

HANNAH ARENDT

AND THE NEGRO QUESTION

HANNAH ARENDT

AND THE NEGRO QUESTION

Kathryn T. Gines

Indiana University Press

Bloomington and Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone 800-842-6796

Fax 812-855-7931

2014 by Kathryn T. Gines

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-01167-1 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-01171-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-01175-6 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 19 18 17 16 15 14

To my mother, Kathleen Smallwood Johnson, whom I watched go to law school while caring for six children and four adults. You taught me about the implications of Supreme Court decisions and their impact on constructions of race and systems of racism.

To my partner, Jason, and our children, Jason II, Kyra, Jaden, and Kalia, for your patience and support through it all.

And to my dearest sisters in writing for our weekly writing retreats and for the precious gifts of encouragement and enthusiasm.

What is important for me is to understand. For me, writing is a matter of seeking this understanding, part of the process of understanding. Men always want to be terribly influential, but I see that as somewhat external. I want to understand. And if others understandin the sense that I have understoodthat gives me a sense of satisfaction, like feeling at home.

Hannah Arendt,

interview with Gnter Gaus (October 28, 1964)

The very process of opinion formation is determined by those in whose places somebody thinks and uses his own mind, and the only condition for this exertion of the imagination is disinterestedness, the liberation from ones own private interests. I remain in this world of universal interdependence, where I can make myself the representative of everybody else.

Hannah Arendt,

Between Past and Future

Contents

Preface

P HILOSOPHER AND POLITICAL theorist Hannah Arendt is among the most insightful and influential intellectuals of the second half of the twentieth century, and her work remains relevant to the global political landscape of the twenty-first century. The ongoing publication and multiple reprints of Arendts books attest to the continued importance of her scholarship. Her correspondence with teachers, mentors, and friends has also been collected and published, attracting additional attention. As Arendts classic writings along with earlier scholarship and personal letters have become increasingly more accessible, her works are being reread and reinterpreted in light of her Jewish identity and what have been described as her Jewish writings. Furthermore, in spite of her distance from feminism, significant feminist interpretations, appropriations, and critiques of Arendt have also brought new perspectives to her work.

One of Arendts great contributions to philosophical and political thought is her mastery of distinction making. She takes familiar philosophical and political terms (like public/political, private, and social; race thinking and racism; imperialism and colonialism; antisemitism and Jew hatredall relevant concepts for my project here) and locates them in an unfamiliar historical framework that encourages a different understanding of the concepts in question. Even if the reader ultimately disagrees with or rejects the distinctions drawn by Arendt, as I often do, she still has the opportunity to think with Arendt about these terms and their connections to one another in provocative ways that result in more acuityas for example when Arendt shows the relationship between imperialism and totalitarianism. Unfortunately, in spite of her insight and influence, Arendts writings about anti-Black racial oppression (or the Negro question) in particular often reflect poor judgment and profound misunderstandings. In her sincere attempts to critique, confront, and even save the Western philosophical tradition, she too becomes entangled within it. In that regard, Hannah Arendt might be seen as a case study for the limitations of the Western philosophical tradition.

I was introduced to Arendts scholarship when I read The Human Condition in a graduate course titled Democracy and Difference. After that, I went on to read and analyze numerous essays, from What Is Authority? to Reflections on Little Rock, and several of Arendts books, from The Origins of Totalitarianism to On Violence. Although I respect Arendts brilliant writing style, her insight, her influence, and her mastery of distinction making, I do not see myself and my experiences as a Black woman adequately represented in her writings about the political in general, or anti-Black racial oppression in particular. Consider the following examples.

In The Human Condition, Arendt distinguishes between the public and the private realms, stressing that excellence achieved in the public sphere surpasses any achievement possible in private. In reading this, I think about all the forms of excellence that are excluded from this model of measuring achievement. Perhaps this model is not problematic for a white, property-owning male whose women, children, and slaves in the private sphere create the conditions for the possibility of him entering the public sphere (as was the case in the model Arendt describes). However this model, which renders invisible that which is done in private space and celebrates that which is done in public space, poses numerous problems for women and people of color, especially those who are activists and intellectuals. When reading Reflections on Little Rock, I am shocked, not by Arendts prioritization of the marriage issue, but rather by her casual relegation of racial discrimination in public education, housing, and employment to social issues. My shock is exacerbated by her suggestion that Black parents who allowed their children to integrate schools were merely seeking upward social mobility. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, I am initially impressed at the connections Arendt makes between racism, imperialism, and totalitarianism, only to become outraged at her condescending and stereotypical characterizations of people of African descent. The frustration continues with her very generous recounting of the conditions under which American slavery is preserved with the founding of freedom in On Revolution, and then her less open-minded reading of Black student protesters and of Frantz Fanon in On Violence.

Although there is no shortage of feminist critiques of Hannah Arendt, I have searched in vain for a comprehensive racial critique of Arendts major writings since I took that graduate course many years ago. Essays have been published on Arendts controversial Reflections on Little Rock and her portrayals of Africans and African Americans in her other writings. Yet there is still no sustained analysis of Arendts treatment of the Black experience in the United States and elsewhere. Toni Morrison has noted, If theres a book you really want to read, but it hasnt been written yet, then you must write it. To this Alice Walker adds, I write not only what I want to readunderstanding fully and indelibly that if I dont do it no one else is so vitally interested, or capable of doing it to my satisfactionI write the things that I should have been able to read. Until now, no book has focused primarily or exclusively on Hannah Arendt and the Negro question in the specific contexts of anti-Black racism and civil rights in the United States; the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions and institutionalized slavery; French and British imperialism and colonialism; and racial violence. Following the advice of Morrison and Walker, this is the book about Hannah Arendt that I wanted to read and should have been able to read.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.