I NTRODUCTION

The system is supposed to have some finality. Its time for that finality.

-Ben Nelson

Governor of Nebraska

July 1, 1996

With those words the fate of John Joubert was sealed. Thirteen years after terrorizing the Midwest, he would pay for his crimes in the electric chair.

The wait for justice had been much too long for the good people of Nebraska. They had wanted the serial child killer exterminated quickly, like a dreaded insect that might threaten future crops. Instead his appeals dragged on and on, until patience finally wore thin and the final decision was handed down by the US Supreme Court. There would be no more stays or delays. To make its point, the court even dismissed Jouberts state-appointed attorney.

As Jouberts time ran out, I made one last trip to Omaha. I had been invited back by KMTV-3, where I had worked and covered the Joubert case, to do commentary about his execution. There was also a chance I would interview Joubert one last time.

We were only hours away from the scheduled execution as I made the two-hour flight from Atlanta to Omaha. I raced from the airport, looking out the windows of my rental car at the fertile fields that passed with a greenish blur. I wondered whether things would go back to normal once Joubert was executed, or whether innocence had come and gone with the US airmans brutal harvest of 1983?

I had struggled for days with what to say if I did get to meet with Joubert. What do you ask a man who is about to be executed and, by all rights, deserves to die? We had not parted on the best of terms. Was he still angry at the words printed in earlier editions of this book? Did he hold me responsible for his conviction in Maine?

After arriving at the TV station, I was ushered into an edit room to look at the videotape of the recent Joubert interview with anchorwoman Trina Creighton.

Joubert had changed dramatically since the last time I saw him. His once boyish, fleshy face had been transformed into a hardened likeness only prison can manufacture. Joubert seemed gaunt and weary, his moppish hair now thinning. A patchy beard gave him a sinister air. Finally, John Joubert looked the part of the savage killer he really was.

He greeted Trina awkwardly. As she moved to adjust his microphone, Joubert winced and withdrew. Again I was surprised at how sheepish the infamous killer appeared in person.

My thoughts faded to my first meeting with Joubert. I was a young investigative reporter fascinated with the case. He was the youngest man on death row.

For more than two years, I had fought for permission to interview him, keeping in touch with his attorney, waiting for this court decision then that one. Finally, afraid that he might be executed before I got a chance to talk to him, I wrote the following letter:

30 Jan., 1987

Dear John,

For the past two and a half years I have followed every step in your case. If he hasnt told you, I have also been in constant contact with your attorney, Owen Giles.

I would very much like to talk to you about the case, life on death row, and the future. Owen has been opposed to such an interview, fearing it might jeopardize your case. I now think were past the point of damage and I have decided to contact you myself. I have talked with Supreme Court Chief Justice Norm Krivosha, who says anything you say now would not affect his handling of your appeal. The way the case was tried is in questionnot the facts.

I feel you have quite a story to tell and must have a lot bottled up inside you. Rest assured, I would be fair in giving you a chance to talk.

Im enclosing a pre-postaged envelope and paper. At least write back. I will come to Lincoln without a crew to talk with you in person if youre interested. Well set the ground rules for the interview. In my opinion, you have nothing to lose, but could gain a little understanding from people, who wonder who John Joubert really is.

Robert Hunt (a former death row inmate) gave me his only interviewbecause, he said, he trusted me.

You can too.

Sincerely,

Mark Pettit, Anchor/Reporter

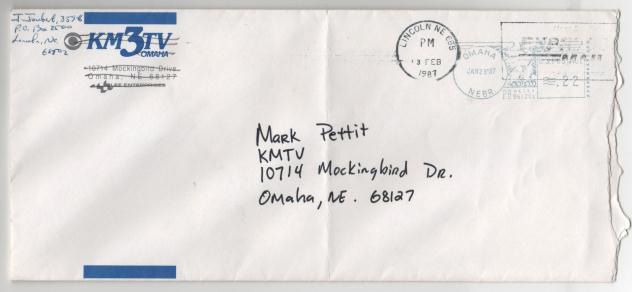

Frankly, I did not expect a response. But two weeks later the envelope came back. The station logo in the top left-hand corner had been scratched out and another return address printed neatly above it.

As I pulled the letter from my mail slot, I had a gut feeling that my request for an interview would be denied, but I was glad that hed written back. I walked into an editing room, sat down, and began to read, fascinated by the level of intelligence with which the letter had been written:

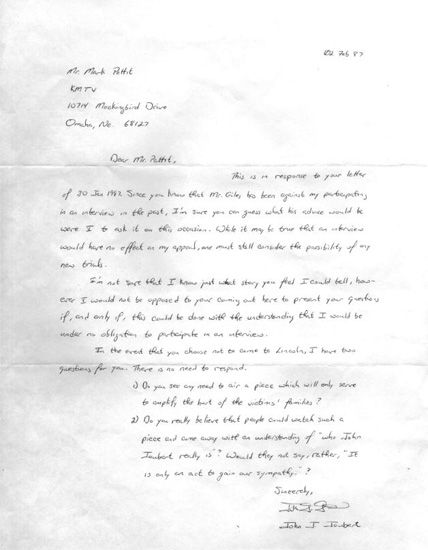

(TEXT OF LETTER)

02 Feb., 1987

Dear Mr. Pettit,

This is in response to your letter of 30 Jan., 1987. Since you know that Mr. Giles has been against my participating in an interview in the past, Im sure you can guess what his advice would be were I to ask it on this occasion. While it may be true that an interview would have no affect on my appeal, one must still consider the possibility of any new trials.

Im not sure that I know just what story you feel I could tell, however I would not be opposed to your coming out here to present your questions if, and only if, this could be done with the understanding that I would be under no obligation to participate in an interview.

In the event that you choose not to come to Lincoln, I have two questions for you. There is no need to respond.

1) Do you see any need to air a piece which will only serve to amplify the hurt of the victims families?

2) Do you really believe that people could watch such a piece and come away with an understanding of who John Joubert really is? Would they not say, rather, It is only an act to gain our sympathy?

Sincerely,

John J. Joubert

Two days later I was waiting in a conference room at the Nebraska State Penitentiary for John Joubert to arrive. Id worried the night before about how to greet him. I despised his brutal crime and was very much aware of the communitys hostility toward him. Still, its hard to talk to a person who knows you hate him. So I decided, as Id said in my letter, neither to condemn nor condone; I would treat him like a human being. I would shake his hand.