Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Susie, Lily, Eleanor, and Lottie XXXX

CONTENTS

What do you call that noise that you put on? This is pop.

THIS IS POP, ANDY PARTRIDGE

INTRODUCTION

If the will of every man were free, that is, if every man could act as he pleased, all history would be a series of disconnected accidents.

LEO TOLSTOY, WAR AND PEACE

54321, counted down the introduction to Manfred Manns 1964 top-five hit, signalling the start of Ready Steady Go! I was a teenager when I first watched a Channel 4 rerun of the show, and as the declaration THE WEEKEND STARTS HERE filled the screen in bold letters, I was transported back to the heyday of classic British songwritingthe time of The Beatles, The Who and The Kinks. The songs put to shame many of the superficial records of the Eighties and invited me to explore a popular music beyond the immediate present.

Having spent a lifetime listening to records and making my own music, I have always been intrigued by the creative process behind popular songs. I was instinctively drawn by the small mysterious piece of information that sat beneath each songs title: the name of the songwriter. I was fascinated to imagine Lennon and McCartney, Pete Townshend or Raymond Douglas Davies plucking words and melody out of the ether, and hunted for information about composition in biographies and magazines. Disappointingly the focus was invariably on the musicians lifestyle. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Paul Zollo wrote a book called Songwriters On Songwriting . It was a collection of interviews with many of North Americas most celebrated writers talking about their craft. It is a compelling and absorbing read. Sometime in the late 1990s I found myself in Borders bookshop on Charing Cross Road asking for the British equivalent. To my amazement, it did not exist. A seed was planted and ten years later I made up my mind to fill the gap.

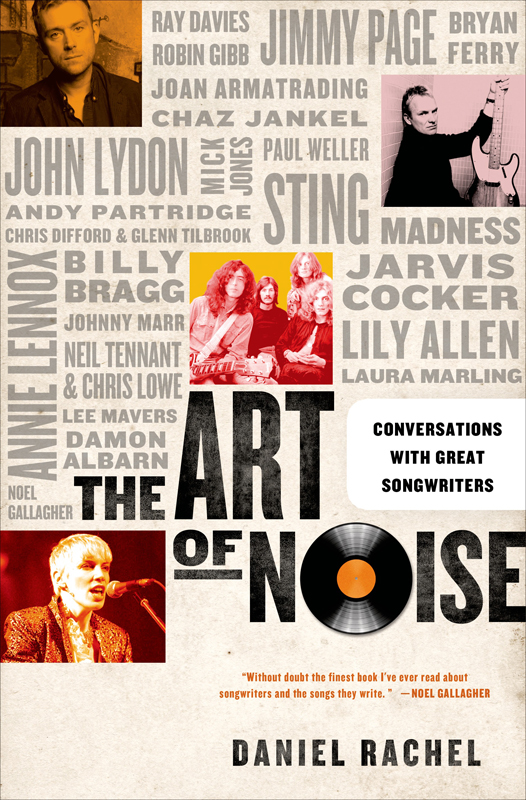

To a songwriter, the question of what comes first, the words or the music, is a tired clich. Writing a song is a highly personal process. If successful, the result is shared with an audience of thousands if not millions, something that requires composers to let go of their precious creations. When I talked with the twenty-seven songwriters in this book I had all my questions laid out in front of me divided into neat themes: Words; Melody; Routine; Audience/Performance; Musicality; Building a Song. I was fascinated by how differently each songwriter responded, and keen to follow up the unexpected insights they offered. Common themes began to emerge, as well as the idiosyncrasies of individual methods. They should be easy to find, whether you choose to read this book sequentially or just dip and skip. The most frequent phrase to appear is There is no one way to write. It is no surprise. The book is a celebration of imagination, and its insights are gained not only from the artists precise analysis of their own methods but also from their self-protective deflections.

In all but two of the conversations (Pet Shop Boys and Annie Lennox) my questions were not submitted ahead of talking with the artist. As a result, what you will read here is the transcription of songwriters words as they collect their thoughts and search for the exact phrases to capture their meaning. It is likely that only a few of the musicians will remember what they said to me until they read this book (although Bryan Ferry, Mick Jones, Madness, Annie Lennox, Pet Shop Boys, Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher all approved their chapters ahead of publication), but the threads of their thoughts reflect their deepest beliefs and working practices. A few stories may seem to be more rehearsed anecdotes from rock n roll mythology, but whilst they may be known by one set of fans, they may be entirely new to the next. The artists are presented chronologically, loosely based upon the timing of their initial impact in musical history. This arrangement reflects developments in politics, social change and recording technology, all of which affect writing, from the language of the lyrics to the equipment of the recording studios and the devices songwriters employ to remember ideas.

I began writing the book by making a list of classic British rock and pop songwriters. Forty or fifty names immediately came to mind, but if the project was to cover fifty years, it felt right to condense the list to twenty-five artists. Since I was taking John Lennon and Paul McCartneys composition and recording of Love Me Do in 1962 as the starting point of modern British music, I decided that the songwriters also needed to be performers. I also tried to give each of the decades from the Sixties to the present day roughly equal representation. By now the list of artists was slimming down to a more manageable thirty names. I discussed my ambition with Richard Thomas, a man renowned for his encyclopaedic knowledge of music and connected to both the rock and pop and the literary worlds. His response was encouraging but also realistic. Musing on why no one had ever attempted this before, he perhaps answered his own question by predicting that only a third of the list would agree to participate and that the project would take at least five years to complete. I then picked up the phone, searched the Internet for contact numbers and names, and began to send out invitations.

People say No because they have not been persuaded to say Yesthis was my maxim throughout the process. I have pestered, annoyed and cajoled in the pursuit of my ambition. I was convinced that the book belonged on the shelves of every music lover, musician, writer and social historian. I clung doggedly to this belief despite repeated rejections from within both the publishing and the music industries. Whilst this is not a definitive work by any stretch of the imagination, I would argue that the artists involved have all contributed uniquely to the progression of classic British songwriting. But what is meant by that term, classic?

A song can get us from A to B as simply and effectively and with the same familiarity as a daily journey to work or a walk to the local pub. But some songwriters choose to take the scenic route. Its still the same starting and finishing point, but our minds have been opened along the way and our senses excited. Along with depth, originality and imagination, great music that makes a lasting impression has an honest craftsmanship running through it. Over time, and often with renewed appreciation, we bestow the word classic upon it.

Equally tricky to pinpoint is the unique character of British music. When we identify music in this way, we are making an association with the spoken voice of our language: dialect, slang, places and names. We recognize our accents and phrases, common codes of speech and our stresses of expression, but at the same time much of our islands musical heritage is imported. It would be a bold musician indeed who would lay claim to British modern instrumental originality. In the wake of The Beatles, Sixties songwriters drew from American R&B, Fifties rock n roll and pre-war genres. Even punk, despite all its posturing and claims to raw self-expression, found its roots in the same music as its predecessors. The beat was simplified and the rhythm straightened, but the style and structures were still essentially American. Reflecting the classical compositions of Walter Carlos ( Switched-On Bach and A Clockwork Orange/Music From The Soundtrack ), electronica, which found favour with so many artists in the Eighties, was born out of a European phenomenon, particularly the Seventies German movement that produced Faust, Can, Neu! and Kraftwerk. Musicians learn through imitation. Their originality is in the revoicing of an influence with creative imagination.