The Girl from Station X

To my mothers four grandchildren

I n the early 1990s, my mother, Anne, began to show the symptoms of Alzheimers, painful for any family. There were other problems. Despite her background of social and financial privilege, my mother had led a life marked by loss, including the premature death of her father and little brother, and the early deaths of two of her four children. She had also been widowed at sixty. For a long time, she had been dependent on alcohol so much so that it was not always easy to differentiate between the deterioration caused by her Alzheimers and the accidents and confusion caused by her drinking. She had also, for many years, been dependent on others and her lack of resilience was a cause of emotional distance between us this came to a head in 1991 when, with two small children and just separated from my husband, I was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Even before she started losing her mind, I was used to seeing my mother as vulnerable and needy and, indeed, had lost sight of her having been any other way. Sometimes I felt I hated her for the disruption she caused. But I also knew her story was not as simple; she had not always been like this.

In the mid-1990s, there was an unexpected development. Her house in Sussex, where I mainly grew up, was sold and she was moved to somewhere smaller. She was a hoarder and it took ages to sort out her belongings. But in her attic in what subsequently felt like a miracle to me a whole box of her diaries was discovered. They began in the 1930s when she was fifteen and continued into the early 1950s. I became gripped by these closely filled-in exercise books, with details of her upbringing, her family, the upheavals and adventures of the Second World War, her romances, the early part of her life as a wife and mother and her enthusiastic travels. But most of all, they told me about my mothers feelings the part of her that had, for so long, remained obscure to me.

I too am a committed diarist, and I felt that she was reaching out to me through her diaries. As I read on, and thought about her writing more and more deeply including attending sessions with a therapist who, when I read out to her passages from the diaries, sensitively cast light on some of my mothers behaviour I began to build up a different picture of her. I talked to my mothers oldest and most loyal friends, and tried to get their slants on her; and discussed her with my children, who each saw her in a different way from me, and from each other.

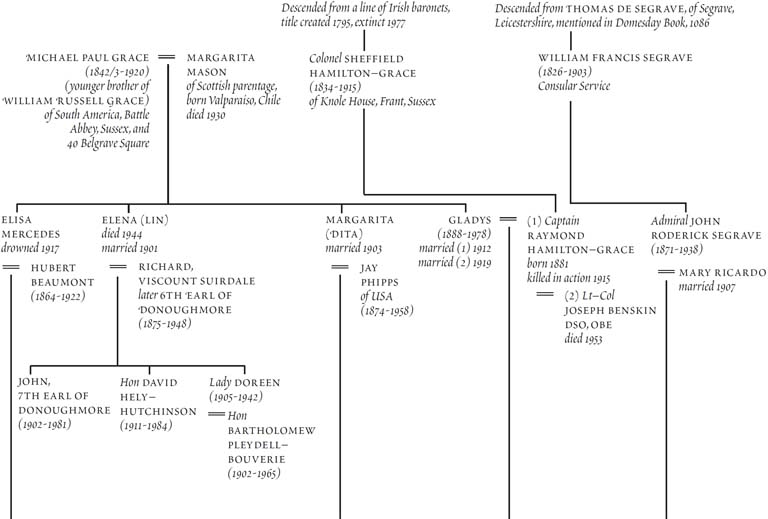

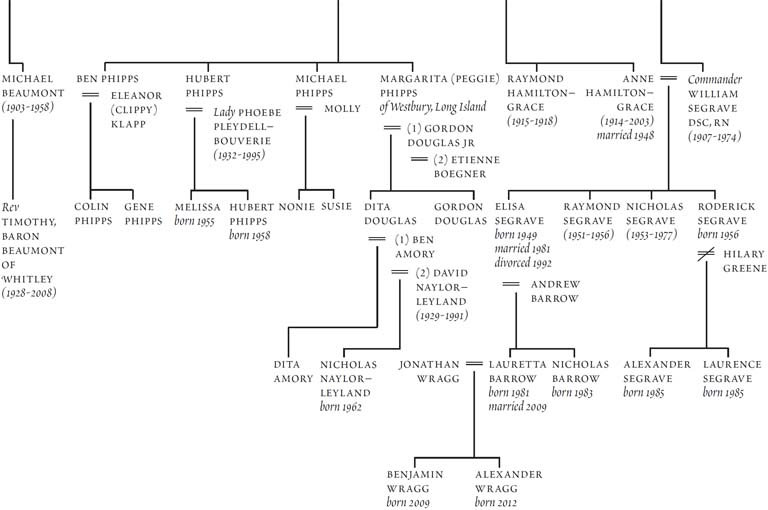

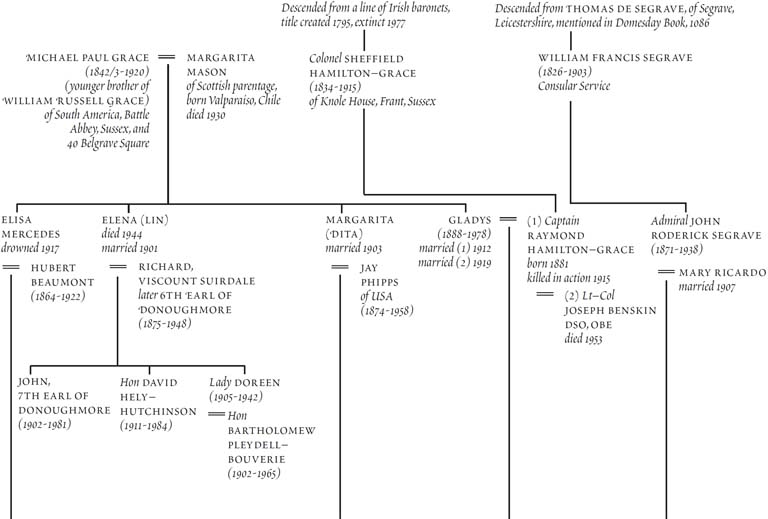

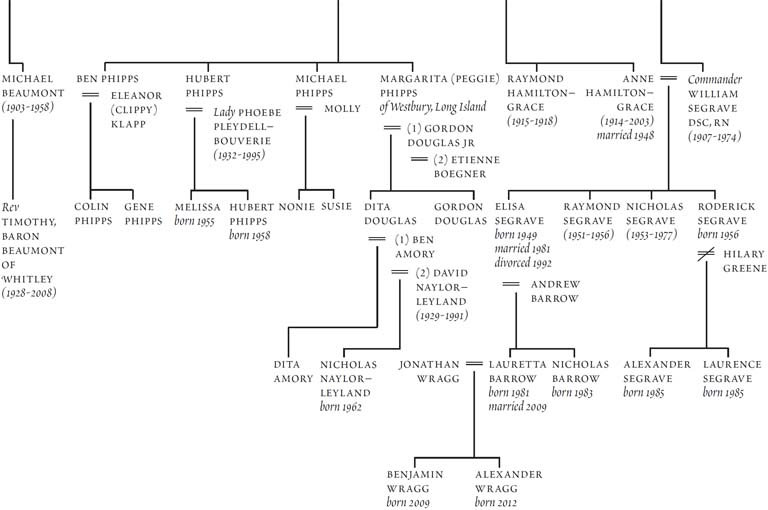

Many facts about her life, of course, I already knew. She was born on 1 July 1914, the daughter of a cavalry officer of Irish origin and of an heiress whose Irish father had made a fortune in South America through guano and shipping; and the early diaries show the world of an upper-class young woman with all its pleasures and luxuries, from finishing schools to tennis parties and balls. I knew also that she had worked in intelligence during the war, having enlisted early in the Womens Auxiliary Air Force. But I had no idea of the roles that she had played during her various posts, which included spells at Bletchley Park, Bomber Command and in post-war Germany, nor of the ability and commitment that she displayed throughout much of the war. Nor was I prepared to read in such depth about the intense emotional attachments that she formed unsurprisingly, of course, given the upheavals of the times.

I decided to write about my mother at first, as an attempt to understand her further. This book is based around extracts from her diaries that, I hope, capture both her and a profoundly unsettled period in British history when a country at war also underwent rapid social change. But I have also tried to convey the singular and often moving experience of gradually uncovering a woman whom I never expected to know so well.

I have changed a very few names for reasons of privacy. My brother Roddy is hardly mentioned, as he has his own story to tell. He was given the opportunity to see the advance text of the book. However, its story and its perspective are mine.

I am very reserved and never show my feelings so that very few people know what I am like inside... I long for romance, I should like to be truly in love with a man and have one in love with me, the real true love, nothing else would do. Im afraid I shall never have the pleasure of marrying anyone as I dont like men.

Diary of Anne aged sixteen, 16 October 1930, Rome.

Chapter 1

I n my mothers garden is a mulberry tree. My mother walks towards me, her hands, drenched with mulberry juice, reaching at my throat. Shes going to strangle me... Elisa, Im getting up at you!

My mother shows me a newspaper. A girl called Elisa, nine like me, was murdered. Her body was found in a cornfield. There was blood on her sock.

My mother sits on my bed at night and talks in an odd, slurry way. I call it preaching she isnt really talking to me but at me. She calls me lovey, but although I often long for her to hug me, this way of talking makes me want to hide under the bedclothes. She sits very close and turns her right hand awkwardly this way and that, a habit that my father imitates when she gets like this, as he does when she declares: Im Irish! Her fingertips are orange, from cigarettes, and a sour smell comes off her.

Often she does not come to say good night to me, so I go up to bed alone to my room at the top of the house. Later I creep down both staircases to listen for my parents; I hear my fathers voice telling her: Go to bed! For Gods sake, go to bed!

I feel the whole house rocking beneath me.

I imagine that I see my mother mounting the last few steps to my landing in her white dressing gown, her eyes screwed up with rage or is it madness?

I remember a beach in Spain, I must be two or three. My mother wades into the sea, leaving me alone on the sand. I cannot see her out there in the waves. Will she ever come back to me?

Spain is where I sometimes have my mother to myself. She is taking me to a childrens party. It starts at my usual bedtime; the family is not English like we are. I go alone with my mother, clinging to her skirts as I remember so often doing then. The party is in a flat and we have to go up in a lift. Getting out, I trip, and start bawling. Inside, the other children are dancing in a circle. I am the youngest. Some of them come towards me and stretch out their hands, inviting me to dance. But I refuse to leave my mother and she is happy to have me with her. Later there is a film show. I am induced to sit on a little chair in a row with the other children. As soon as the lights go out, I yell. Very quickly, I am reunited with my mother. I spend the rest of the evening holding on to her.

I am the firstborn, I am my parents darling. My father calls me Button Nose. He holds me high on his shoulders and pushes me very fast in my pram up and down Madrids wide avenue, the Castellana. My father, who works in the Embassy, is proud of me and of my first sentences: Button Nose has buns for tea and I can do it!

In the summer, my mother takes me and my younger brother Raymond born in May 1951 to the seaside in the north of Spain. At the entrance to the beach sits a poor woman, selling apples. My mother buys her apples each day. Her children ten or more of them have no toys. Sometimes they steal our buckets and spades and the little boats we bring to the beach.

Next page