Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

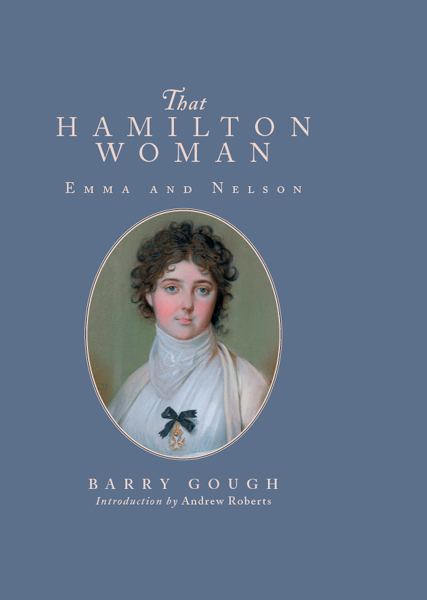

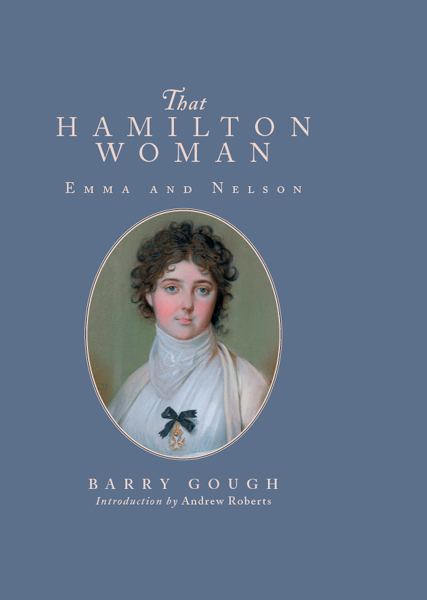

Front cover: Emma painted by J Schmidt, Nelsons favourite depiction of her. See .

Copyright Barry Gough 2016

That Hamilton Woman essay Estate of Arthur Marder 2016

Introduction copyright Andrew Roberts 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4738 7563 0 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 978 1 4738 7565 4 (EPUB)

ISBN 978 1 4738 7564 7 (KINDLE)

ISBN 978 1 4738 7566 1 (PDF)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Barry Gough to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by MATS Typesetting, Leigh-on-Sea

Printed and bound in Malta by Gutenberg Press Ltd

Contents

by Andrew Roberts

Dedication

For Lawrence Phillips

People will be very sorry they spoke so cruelly of me. One day they will see that they were abusing a tragic figure.

SUSAN SONTAG, writing of Emma. The Volcano Lover: A Romance (1992)

It is strange to observe how the unfortunate Emma mingles herself with the life of Nelson. The student cannot get away from her. She is as a strand in the rope of his career, and makes herself as much a portion of his later life as if she had been a ship or a battle.

W CLARK RUSSELL, Pictures from the Life of Nelson (1897)

List of Illustrations

Between pages 32 and 33

Between pages 48 and 49

Between pages 64 and 65

Between pages 80 and 81

Between pages 96 and 97

Introduction

T he 1941 classic movie That Hamilton Woman, starring Laurence Olivier as Horatio Nelson and Vivien Leigh as Emma Hamilton, was made in Hollywood by the great Hungarian-American film producer Alexander Korda. It was boycotted by the isolationist, anti-war America First Committee when it was released for its obvious propaganda overtones, such as the moment when, hearing of Napoleons peace offer, Olivier states: Gentlemen, you will never make peace with Napoleon Napoleon cannot be master of the world until he has smashed us up, and believe me, gentlemen, he means to be master of the world! You cannot make peace with dictators. You have to destroy them wipe them out! Small wonder that it was Sir Winston Churchills favourite film and that he was said to have watched it seventeen times.

Barry Gough has written an excellent overview of the story of the hero and heroine of That Hamilton Woman, whose relationship still today constitutes a love affair to stand beside those of Antony and Cleopatra, Romeo and Juliet, Napoleon and Josephine (the last of whom died only eight months before Emma Hamilton). It was an extraordinary tale. One moment Emma was the gorgeous, buxom, rouge-cheeked temptress of the Romney portrait at the Frick Gallery in New York, striking her Attitudes and fascinating a series of upper-class patrons who passed her on from one to the next. Then, after the briefest of interludes as Admiral Nelsons lover, she became a debt-ridden, obese alcoholic eking out her existence in the Calais stews. The tragedy is tangible.

I have an invitation to Nelsons funeral close to my desk, at which ceremony all the eight admirals who carried his coffin at St Pauls Cathedral in January 1806 were in floods of tears. Regency men didnt mind expressing their feelings in a way that their Victorian children and grandchildren felt they couldnt. Yet if Nelson had lived, and become the Duke of Trafalgar, this story would hardly be known today; Emma would have become just another podgy, early nineteenth-century duchess.

Emmas transformation from beloved beauty to destitute has-been was brilliantly told by the distinguished American naval historian Arthur Marder in one of the finest speeches he gave in a long and distinguished career of writing and lecturing, which is reproduced here in extenso. Marder rightly emphasises the sheer sex appeal of Lady Hamilton, an essential feature of her personality, but one that Victorian and later writers tended to underplay, out of prudery. One suspects that one of the reasons Regency Society rejected Emma Hamilton was because wives understandably refused to allow their husbands to go anywhere near such a sex-goddess. In recent years the historians Flora Fraser and Kate Williams have followed Marder in rectifying this lacuna in the historical record.

Where Barry Gough does naval historiography a great service in this book is to place Lady Hamiltons story in the wider context of the huge importance of women to the running of the Royal Navy in the age of fighting sail. In what seems at first sight very much an all-male Senior Service, it actually turns out that women were highly important to almost every aspect of the life of the British Fleet, in ways that will surprise readers. Goughs clear admiration for other Nelson historians Andrew Lambert, Roger Knight, John Sugden, Edgar Vincent and Colin White among them reminds us that since the Trafalgar bicentenary in 2005 we have been living through a veritable golden age in Nelsonian scholarship. This diligently researched, well written and richly illustrated book, and the superb exhibition at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich which it complements, are eloquent testament to the continuation of this wonderful renaissance.

PROF ANDREW ROBERTS

Visiting Professor, Department of War Studies,

Kings College, London

Preface & Acknowledgements

I n bringing Arthur Marders typescript into print after all these years the publishers have given honour to a great historian and a great subject. The occasion of the special National Maritime Museum exhibition on Emma, Lady Hamilton, on the date of this books publication, marks a true recognition of Emmas importance in history. That Hamilton Woman is the title of the 1941 film, and this too affords us the opportunity of looking at this famous love affair as it has been portrayed on screen. In the movie the son of Fanny Nelson, Josiah Nesbit, then a young naval lieutenant, derisively calls Emma that Hamilton woman. He was loyal to his mother but, having seen all the goings on at Naples, probably lusted after Emma. He was, in the authors opinion, the source of much of the bother. One further point may be made, and it is this: Women have been a central figure in Englands rich and remarkable naval history, and in the following text I have given attention to the theme of that yet to be written book the women behind the fleet. Navy wives, mistresses and sweethearts often wore more gold braid than their men, and in Emma, Nelson had his woman behind his fleet. The success at Trafalgar owes more to Emma than has ever been properly admitted, and the National Maritime Museums attention to this enduring theme is worthy recognition of the importance of that Hamilton woman, the smithys daughter who rose from obscurity to become lover, inspiration and partner of the greatest of Britains admirals.