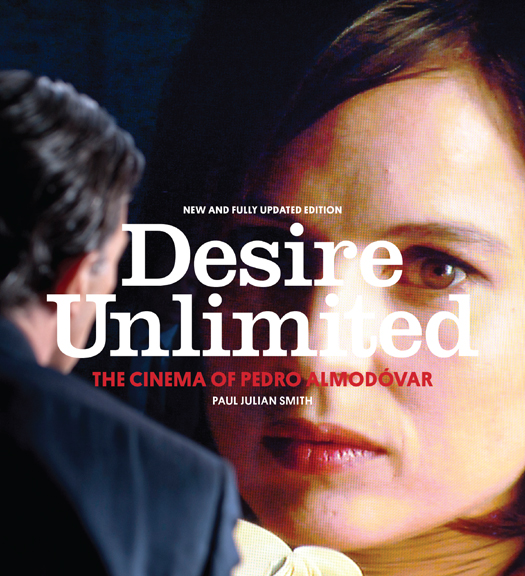

This third edition first published by Verso 2014

First published by Verso 1994

Second edition published by Verso 2000

Paul Julian Smith 1994, 2000, 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-177-0

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-222-7 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-531-0 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

This third edition is dedicated to my students

and colleagues at the Graduate Center, CUNY

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

As I wrote the preface to the second edition of this book in November 1999, Almodvar was coming off his greatest success to date. Todo sobre mi madre (All About My Mother) was still playing in cinemas around the world and would go on to win its director the prizes that had hitherto eluded him (an Oscar for Best Foreign Film and Goya for Best Feature) and to attract a domestic audience in Spain of an astonishing two and a half million.

It is once more a great pleasure to note that, apparently unintimidated by the high bar he had set himself, Almodvar has gone on in the decade that followed to produce five new features that are ambitious and varied, both adding to a coherent and recognizable oeuvre and bringing distinct and distinctive innovations to that ever growing body of work. Thus Hable con ella (Talk to Her, 2002), a sober hospital-set story, boasted a daringly complex plot tracking four main characters, which resolved only slowly into an intimate connection between them. Rightly it won Almodvar another Oscar, this time for Best Original Screenplay, a unique achievement for a foreign-language film. This must have been a special pleasure for the director, given that traditionalist Spanish critics had sometimes criticized him precisely for weaknesses in plotting.

La mala educacin (Bad Education, 2004), a pitch-black drama on child abuse by priests, was Almodvars first feature to be based wholly in the past, albeit skipping backwards and forwards between three periods: the late Francoist dictatorship, the Transition to democracy, and the movida period of cultural effervescence with which Almodvar has remained closely connected since his debut Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980). Almodvars first feature in almost twenty years to focus on gay men (the previous one had been La ley deldeseo [The Law of Desire, 1987]), it was also praised by J. Hoberman, the distinguished New York critic, as his best film in two decades.

Volver seemed at first sight, and as its title indicates, to be a return to the past, boasting as it does a new and moving collaboration with Carmen Maura, the unforgettable star of Qu he hecho yo para merecer esto? (What Have I Done to Deserve This?, 1984) and Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, 1988). Yet if its rural setting also seemed to suggest a regression for Almodvar (who was famously born and raised in the agricultural region of La Mancha), it featured for the first time a supernatural plotline, with Mauras ghostly mother returning to haunt the traumatized daughter played by Penlope Cruz. Volvers very accessible pleasures (notably Cruzs transformation into a bona fide movie star whose look was inspired by Sophia Loren and a satisfying reconciliation between the two estranged main characters) attracted the largest domestic audience of Almodvars late period, almost two million.

Los abrazos rotos (Broken Embraces, 2009) was made of sterner stuff and permitted no final reunion between its film-director protagonist and a tragically lost lover, played by Cruz once more. A newly chilly tone reflected on the paradoxes of filmmaking (whose miraculously preserved subjects are compared to the lava victims of Pompeii, immortalized at the moment of death) and the intermittences of the heart (which seems in Almodvar ever fated to be frustrated). Seeking new territories and locations, Almodvar shot much of Los abrazos rotos amongst the ominously black sand and rock of the Canaries.

Finally, La piel que habito (The Skin I Live In, 2011) was Almodvars first film to be presented as a horror movie. Based, unusually, on a source novel, whose shocking plot twist is faithfully preserved, La piel serves still as a kind of back catalogue or anthology of the eighteen features to date, including as it does a troubling rape scene reminiscent of Kika (1993) and the clinical setting that has featured in every film since La flor de mi secreto (The Flower of My Secret, 1995). It also marked a reunion with Antonio Banderas (as Volver did with Carmen Maura), who had not worked with Almodvar since the similarly themed tame! (Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, 1990). In June 2012 La piel won Agustn Almodvar, Pedros faithful producer brother, a prize from FAPAE, the Spanish producers association, for the highest-profile international release of the previous year: the film had been sold to forty-two territories and been seen to that date by 4.2 million people around the world.

Beyond the striking diversity and originality of this recent corpus, there is a significant thematic continuity here: a continuing reflection on creativity and the artistic process. Thus, most evidently, the main characters of La mala educacin and Los abrazos rotos are film directors. But Hable con ella boasts lengthy extracts of performances by Pina Bauschs company, proposing dance as an analogue for the moving bodies of cinema; and Volver features a climactic sequence in which Cruz lip-synchs a flamenco version of the classic Argentine tango which gives the film its name, suggesting a musical paradigm for the feature as a whole. More grimly, the surgeon of La piel que habito pieces together fragments of artificial skin for his surgical victim, a disturbing analogue for the suturing of celluloid in cinema.

While such sophisticated self-consciousness could be seen as part of the transition from a frivolous rose to a more mature blue period, which, as I suggested in my second edition, is thought by some critics to have begun with La flor, it has not precluded the continuing presence of elements of the crazy comedy for which Almodvar first won fame. Thus there is the sly verbal humour of Chus Lampreaves caretaker in Hable con ella, when she acknowledges that the imprisoned Benigno is innocent, but still asks, Innocent of what? Or again, Carmen Mauras ghostly mother in Volver, often so moving, is not averse at certain points to farting or hiding under the bed in classic farce style. If (as I argued in the first edition) Almodvars early films are not lacking in seriousness (seeking truth in travesty), then his later works are hardly devoid of humour. Indeed at the time of writing, Almodvar has just begun to shoot a new feature,