Table of Contents

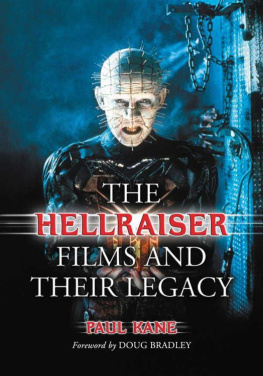

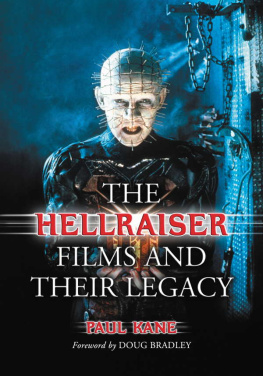

The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy

Paul Kane

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

All the photographs and images used in this book are from private collections and picture libraries and are used solely for the advertising, promotion, publicity and review of the specific motion pictures they illustrate. They have not been reproduced for advertising or poster purposes, nor to create the appearance of a specially licensed or authorized publication. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for the use of their material. All rights reserved. While every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge all creators and copyright holders, the author apologizes for any errors or omissions and, if informed, will be glad to make corrections in any subsequent editions.

Clive Barker, Gary J. Tunnicliffe, Doug Bradley, Randy Falk (NECA), Stephen Lane (The Prop Store of London), Les Edwards, Phil and Sarah Stokes (Revelations), Marc Calma and Kacey Rodriguez, David A. Magitis, Eric Gross, Shelly Berggren, David Robinson, Eric Horton, Mark Thompson (Checker Books), Gabrielle White (Random House), Dan Cope, Nathan Green, David Stoner (Silva Screen), Rita Eisenstein (Starlog Group), Ian Frost and Dan Forbes.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kane, Paul, 1973

The Hellraiser films and their legacy / Paul Kane ; foreword by Doug Bradley.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-2752-9

(illustrated case : 50# alkaline paper)

1. Hellraiser filmsHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1995.9.H42K36 2006

791.43'67dc22 2006029845

British Library cataloguing data are available

2006 Paul Kane. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

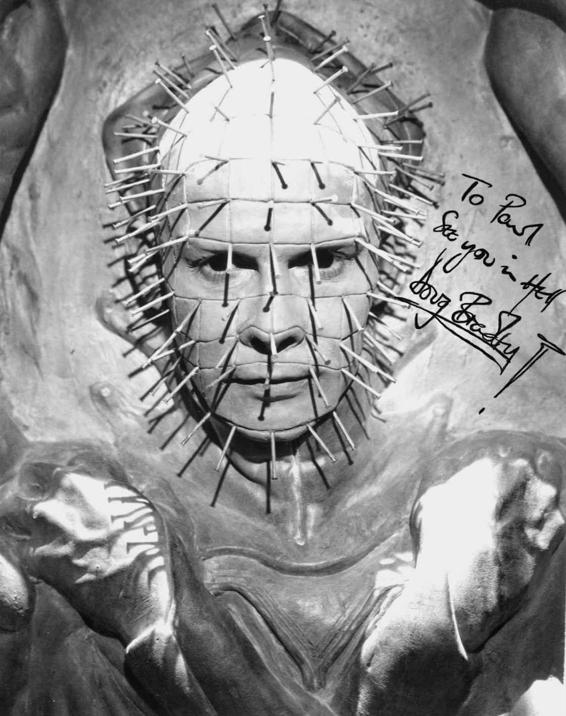

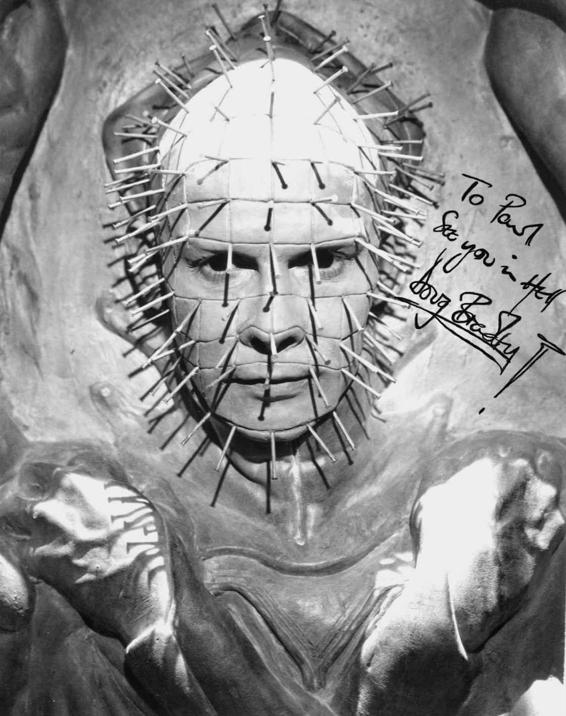

On the cover: Doug Bradley as the Lead Cenobite (Pinhead) in Hellraiser (New World Pictures/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Eric Popplewell and Shelley Baker:

tutors and friends.

You pulled back the magicians curtain

and allowed me to look behind.

With huge respect and thanks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book couldnt have been written without the help and support of so many people: My mum and dad, and the rest of my family, Clive Barker, Kurt Adam, Doug Bradley, Stephen Jones, Michael Marshall Smith, Kim Newman, Peter Atkins, Gary J. Tunnicliffe, David Robinson, Randy Falk, Les & Val Edwards, Frazer Lee, Shelly Berggren, John B. Ford, Simon Clark, Russell Blackwood, Shannon Larratt, Alec Worley, Joseph ORegan, Bob Keen, Mark Thompson, Eric Gross, Yoram Allon, Max Lichtor, Allan Bryce, Constance Taylor, Nathan Green, Dan Cope, Peter E. Keighrey, Rita Eisenstein, Ken Patterson, Eric Horton, Christopher Fowler, Martin Roberts and Helen Hopley, Marc Calma, Lee Glasby and Claire Wood-Glasby, David Stoner, Peggy J. Shumate, Gabrielle White, Kevin Knott, Judith A. and Scott Richard, Ken Snyder, Phil and Sarah Stokes, David Bamford, Dan Forbes, Caroline Noonan at HarperCollins UK, Peter London at HarperCollins US, Ian Frost, Neil Gaiman, Ed Martinez, Tim Lawes, Stephen Lane, David A. Magitis, and, of course, Marie ORegan, who has been my anchor while writing this book and who persuaded me to do it in the first place. A big thank you to everyone.

FOREWORD

by Doug Bradley

It is, as I write this, exactly nineteen years to the month since the cameras were rolling at Cricklewood Production Village in North London on a largely unheralded, British-made, American-produced horror film whose darkly enigmatic subject matter provides the inspiration for this book. In the intervening time, I have been pretty thoroughly cross-examined about that same subject matterin print, on radio and TV, in person at conventions and, latterly, increasingly via emailand in particular, of course, about the role of those mysterious leather-clad theologians of the Order of The Gash and their unceasing explorations in the higher reaches of pleasure.

In a question and answer session more than ten years ago, I recall being asked, Do you think the ending of Hellbound suggests that there is no possibility of Heaven, only the certainty of Hell? I didnt have an answer then, and Im not sure I do now. More than likely I turned the proposition back on the questioner to buy thinking time: Wow, thats a great question. Im not sure. What do you think? Or I may have fled to The Last Resort, what might be called, with thanks to the United States Constitution, the Actors Fifth. Hey, come on, guys. Its just a movie, you know.

More recently, Ive found myself approached on film sets with the query, What do you think, Doug? Are we allowed to do this? What do you mean, allowed to do it? Well, is it right? Does it fit the mythology? In those situations, I feel like some kind of representative for the Union of Cenobites and Assorted Soul Tearers. Hold on, Ill just consult my manual. Now look: page 42, clause 3, paragraph E, section (i) clearly states.... In fact, my answer tends to be: if it feels right, do it. Its more a question of ideas being good or bad, exciting or dull, original or hackneyed, rather than right or wrong. Besides, if something is going to have the temerity to claim the name of mythology for itself, it cannot be finished or immutable: it must be fluid, constantly changing and modifying, and have the ability to be one thing today and something quite different tomorrow.

I have good reason for taking this approach. Towards the end of filming Hell on Earth I sat in the bar of the Howard Johnson hotel in High Point, North Carolina, listening to a fellow cast member outline his idea for the fourth film. I dont remember the details, but it somehow involved the Lament Configuration and, by extension, Pinhead being fired into outer space to rid the earth of its power. It would somehow find its way onto a space station and.... Well, I think I nodded politely while feeling that he should possibly spend less time in the bar. Pinhead in space? Dont be ridiculous. And look what happened next. I dont think , by the way, that I ever recounted that story to Clive Barker.

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth still (photograph credit Keith Payne).

I think I know Clive well enough to assert that if you give him a rule book, his first instinct will be to torch it: tell him what he cant do and hell gleefully roll up his sleeves and dive right in. Catch him in a mischievous mood, and hell be the first to say, Look, this is an entertainment I dreamed up to enliven a drab Tuesday afternoon in February. Its not that big of a deal. Or, as he once said to an audience when sharing a stage with me at a Fangoria convention, Its just a guy with a bunch of nails banged into his head. Get over it.

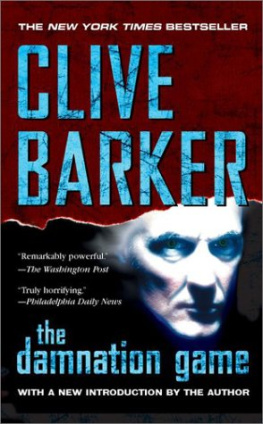

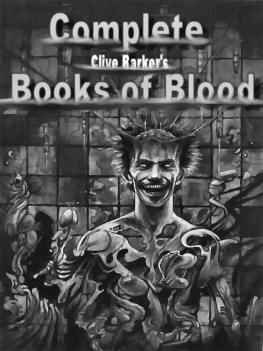

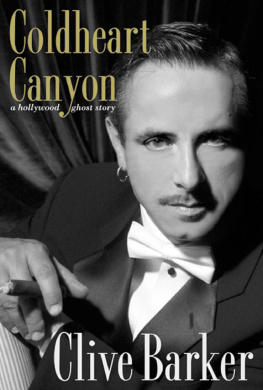

But this is Clive Barker, so its not quite that easy, is it? As with all his work, the ideas in his divertissement of a dysfunctional family and the nasty secret in its attic, his sonata for puzzle box, hooks and chains, linger in the mind long after the film has finished: fascinating and frightening, delighting and disturbing. And it has continued to do that for millions of people around the planet across nearly two decades, eight (to date) films and numerous comic strips, graphic novels and who knows what other manifestations.

Next page