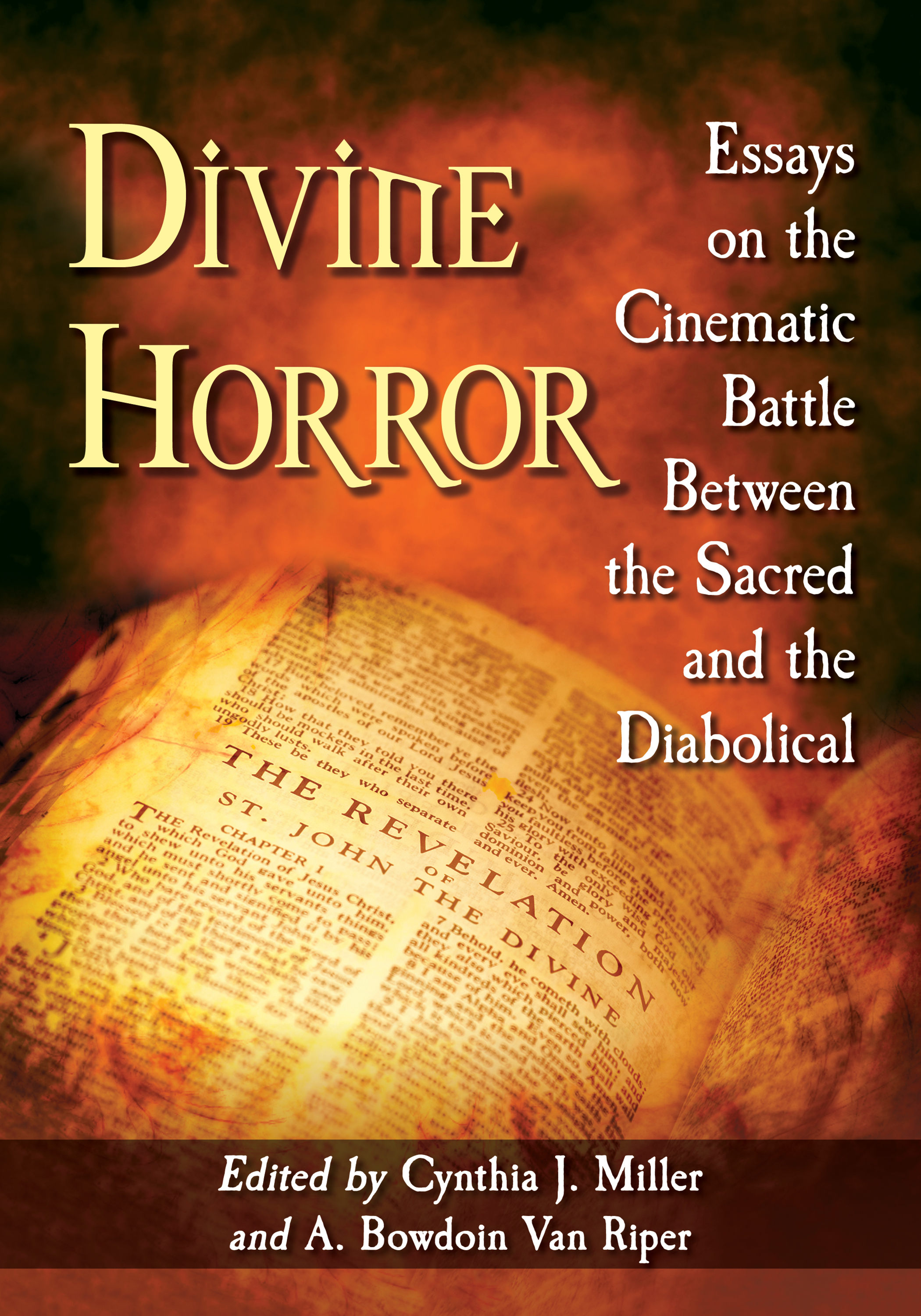

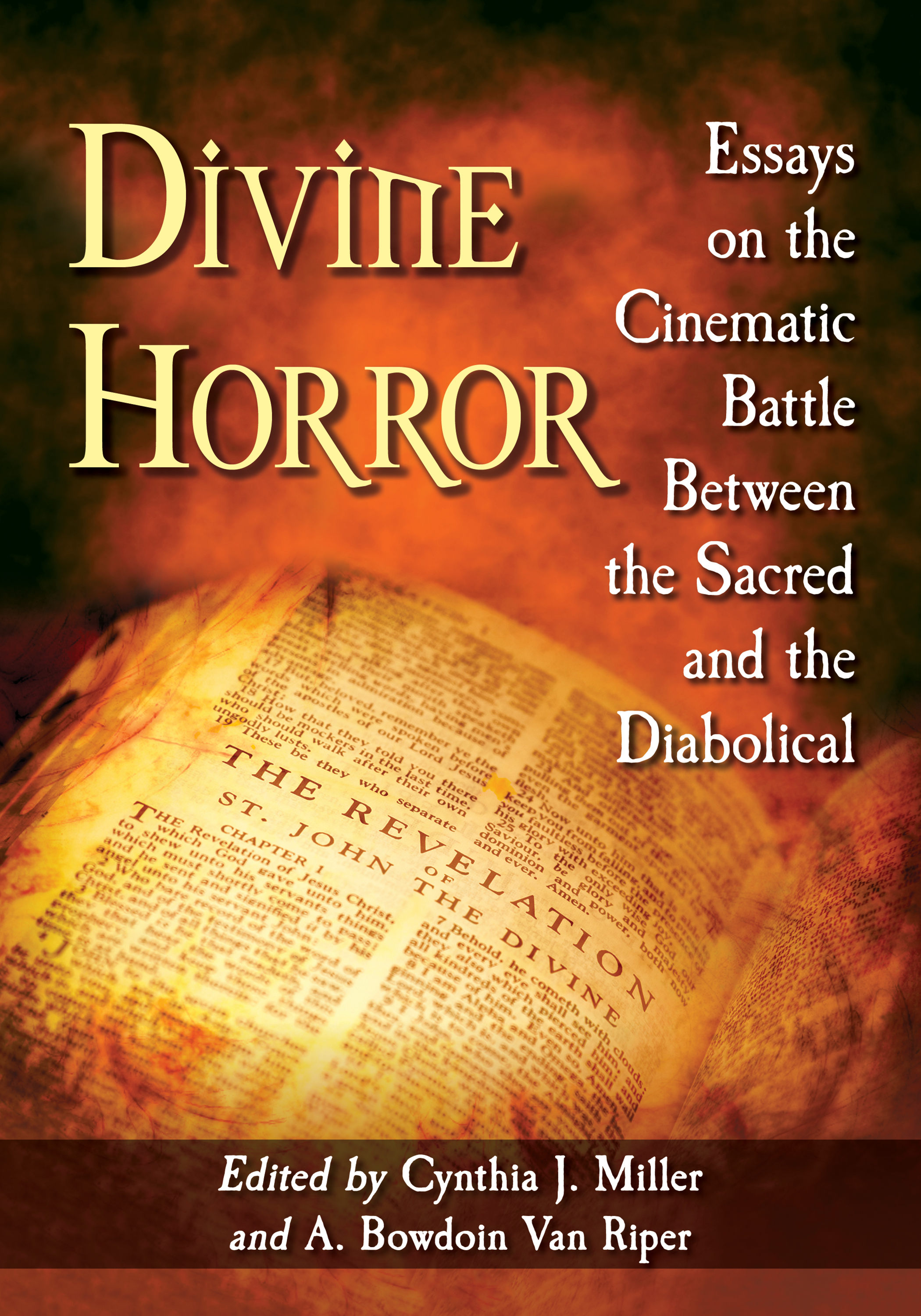

Divine Horror

Essays on the Cinematic Battle Between the Sacred and the Diabolical

Edited by CYNTHIA J. MILLER and A. BOWDOIN VAN RIPER

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2984-1

2017 Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover images 2017 iStock/Thinkstock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For those who fear the hounds of hell,

whose earnest prayers keep evil at bay;

And those who dance beneath the moon,

then vanish at the break of day

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful that this volume has come into being at the hands of so many thoughtful and talented scholars, and we would like to thank each of them for their contribution. Thanks also go to Cynthias Making Monsters students for their inspired invocations of gods, demons, witches, and even Satan himself as the sources of failed alarms, crashed computers, and erased film footagecausing her to believe that, indeed, supernatural forces are at work in the world.

Introduction

CYNTHIA J. MILLER and A. BOWDOIN VAN RIPER

I will send my terror in front of youExodus 23:27

Terror fear dread. All have been cited as primordial elements of the divine-human experience since the beginnings of civilization. It has been suggested, in fact, that religion finds its genesis in fear: It is this feeling which, emerging in the mind of primeval man, forms the starting point for the entire religious development in history. Deamons and gods alike spring from this root, and all the product of mythological apperception or fantasy are nothing but different modes in which it has been objectified. This attraction is so potent, in fact, that its resonance is capable of endowing secular objects, symbols, and narratives with a similar visceral force.

Interwoven with this sacred terror is a fear of supernatural evil. New Testament scriptures warn of demonic spirits that perform signsthat deceive, plague, and possess.

Thus, even while we are alive, our traditions tell us, we have much to fear in both the power of the light and the menace of the darkness. From this deeply felt, partially shared, often conflicted religious heritage derive tales of Divine Horror, giving voice to fears and fantasiesboth sacred and secularof the monstrous and marvelous, the seen and the unseen. As Douglas Cowan relates, what we fear, how we fear, and the ways in which we react to fear are profoundly shaped by the cultures in which we live. The narratives we employ to express these fears change and evolve as well, bearingsometimes boldly, sometimes subtlythe stamp of the time and place in which they were created.

Motion pictures have added multiple dimensions to these tales, allowing (perhaps compelling?) us to see what we could once only imagine. Likewise, contemporary cinematic horror, with its reliance on visceral reactions and psychological unease, has provided a fruitful home for stories of supernatural dread and menace, along with an audience that shares a common visual lexicon for things fearful. The result has been half a century of speculative fantasies about Heaven and Hell, God and Satan, blessings and possessionfilms that address the social, political, and existential hopes and fears that have brought these tales into being. A selection of these films, produced in the decades between Rosemarys Baby (1968) and the present day, are the subject of this book.

Gods and Monsters

Belief in the presence of divinity and evil in the world is as old as humankind. Myths and lore of ancient civilizations, along with the sacred texts of major world religions, chronicle the acts of gods and demons, in various forms and guises, as vehicles for both inspiration and social control. Whether toying with humans for amusement, manipulating them in the service of greater goals, or testing their devotion and obedience, tales of active supernatural intervention in the human realm abound.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, early scriptures are shot through with vivid images of a mighty, just, but wrathful God whose angelsdeliverers of both destruction and restorationappear in flames, smite firstborn children, and rescue the pious. Tests and trials abound: Lots wife disobeys the Lord and is transformed into a pillar of salt; Abraham is commanded to murder his son as a display of devotion. Allusions to an ever-present evil drawn from the old lore of the Canaanites persist, but are put to rest through more analytical readings of the works and will of the Almighty.

Over time, however, the sacred history of humankind has come to be popularly understood not as a struggle between divine good and human evil, but as a cosmic battle for the souls of humankind, with Satan as the supernatural embodiment of malevolence and sinthe Adversary. Beginning with the notion of Original Sin, in which the Devil is portrayed as a serpentine presence that brings temptation and corruption into the world, human history has been shaped by the belief that both God and Satan have the ability to manifest their power and will on Earth, parting the veil between our reality and the supernatural realms of heaven and hell.

Key to this shift is the New Testament figure of the Christthe Son of Godwhose life on Earth in human form (born to a virgin untainted by original sin, thanks to her immaculate conception) erases, perhaps forever, the boundaries between the supernatural and the mundane. Christ is credited with routinely performing miraclesrestoring sight, healing sickness, bringing the dead back to lifeand ultimately, emerging from his tomb to walk among men and ascend into Heaven. With the introduction of the Christ came manifestations of the Devil in scriptures and other sacred texts. The Devil figures prominently in the New Testament, actively working against divine intervention in the affairs of the world and the fate of humankind. Demons, Satan, Beelzebub all are acknowledged in the synoptic gospels, as are numerous instances of demonic possession, serving as illustrations of the divine power of the Christ when they are cast out of their unwilling hosts and vanquished from the Earth.

The agency of the Christ in the world after his ascension is affirmed and maintained through sign and symbol, as homes, hospitals, and sacred spaces display likenesses of his tortured, bloodied, and crucified body. Likewise, through the Eucharistthe ritual of Holy Communionduring which the substance of the elements are converted into His body and blood. As Cardinal John OConnor instructed, To receive Holy Communion in the Catholic Church means that one believes one is receiving, not a symbol of Christ, but Christ Jesus himself.

As presence came to be seen as evidence of superstition, of magical thinking, of the infantile and irrational, the primitive and the savage, in the modern era, however, the unseeing of gods was required. Statues of Mary wept blood, stigmata afflicted the righteous, and the countenance of the Christ appeared on walls and in objects as if by magic.

Next page