O UTCAST

(19011925)

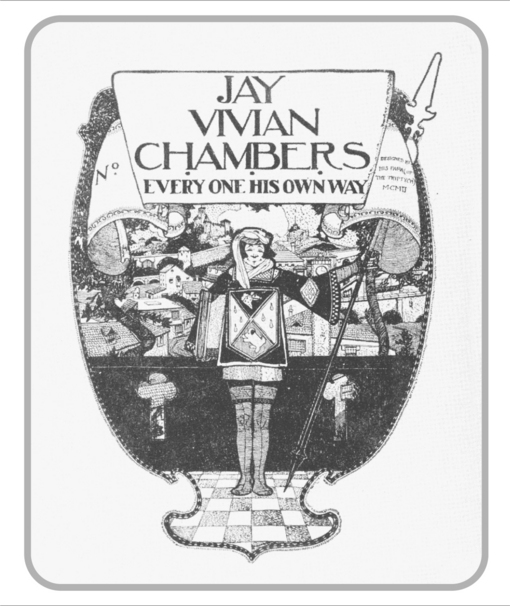

Bookplate designed for the infant Jay Vivian Chambers by his father, Jay, in 1902.

PRINT COLLECTION, MIRIAM AND IRA D. WALLACH DIVISION OF ARTS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS, THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASTOR, LEXON AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS

Vivian

Jay Vivian Chambers was born on April 1, 1901April Fools Day, as he liked to point out. He was named for his father, Jay Chambers, a graphic artist at the New York World. The boys middle name, chosen by his mother, Laha, dismayed her husband and also its bearer, called Vivian all through childhood. Jay, however, refused to utter the hated syllables and so inflicted on his son the nickname Beadle, evidently a comment on his demeanor, watchful, grave, and severe.

In 1903, after a second son, Richard, was born, Laha decided the young family should move from their apartment, near Prospect Park, Brooklyn, and resettle in the suburbs. She loathed New York City and missed the open spaces she had known in her own childhood, spent in Wisconsin.

Jay resisted the move. A city boy from Philadelphia, he enjoyed Brooklyn, its brownstones and tree-lined pavements. He liked too the easy access, by elevated subway, to his Manhattan office and the theaters and galleries he frequented. Also, he had recently lost his job at the World to a news camera, and although he soon found new employmentwith a design studio on Union Square that did book covers and magazine illustrationsthe venture was in its infancy and its prospects uncertain.

But Laha, insistent and strong-willed, prevailed over Jay, who was passive and retiring, and in 1904 the family moved to Lynbrook, a pretty coastal village on Long Islands South Shore, twenty miles east of Manhattan, with a population of less than two thousand. The year the Chamberses moved there, Lynbrook got its first water mains and its first brick building, M. L. Levinsons Hardware Store.

Lahas father, Charles Whittaker, a Scottish immigrant born in 1840, had immigrated to Milwaukee in 1845, with his parents and twelve siblings.

Even as he advanced his pedagogical career, Charles pursued other interests. He was the founding publisher of Milwaukees first city magazine and registered several patents.

She went instead on the stage, touring the Midwest and Far West with stock companies.

These distinctions meant little to Jay. He cared only for art. A product of the 1890s, the mauve decade, he quietly deplored middle-class standards of respectability. While Laha strove to establish the family in Lynbrook, Jay stood to the side, mocking. He regarded the suburbs and their inhabitants with droll disdain. He once bet a friend he could walk to Lynbrooks center, the Five Corners, clad only in his pajamas and not attract a single comment from his complacent neighbors. He won the bet. At home he raised the gaudy pennant of aestheticism. He wore a linen samurai robe, planted a large replica of the Venus de Milo on the living room floor, and mounted on its walls a permanent exhibition of his bookplates (prized by collectors) and whimsical Christmas cards (prized by his friends).

It amused Jay to adorn the house, but he steadfastly refused to fix it, despite its poor condition. The yellow exterior coat had been bleached of color by the salty ocean winds. The shutters, a sickly green, nagged at their rotted hinges. The interior was even worse. One day a portion of the dining room ceiling dropped. Laha covered the hole with cheesecloth. Vivian and Richard watched transfixed as mice nested in its bulges, their scampering feet leaving twinkling impressions. Another project was the wallpaper, aged and blistered. Jay would not replace it. Laha wrapped up her few valuables and took them to Manhattan pawnbrokers, returning with enough cash to hire a team of workmen. When the job was finished, Jay said nothing. Lahas sobs were dreadful to hear.

But she was not deterred. With or without Jays encouragement, she was determined to carry her mission forward, to conquer Lynbrook in the name of her sons, anchoring them in the community. She was

Yet the Chamberses never quite blended in. Neighbors found them clever and brilliant but faintly disreputable. The house, cluttered with Jays artwork and the mismatching antiques Laha rummaged up, had the appearance of a seedy museum. And its curators were themselves odd: the plump, aloof artist who rode the commuter train in virtual silence; the actressy wife with her stagey voice and florid gestures, her talk of important friends in the theater. Locally, they were referred to as the French Family.

Vivian early realized his family was peculiar. More painful still, he watched his parents marriage crumble. Laha craved affection from all those around her. Jay would notor could notgive it. The couple enacted rituals of devotion, but the children were not fooled. Each evening Laha ceremonially positioned Vivian and Richard in the front hallway so they could plant a kiss on their fathers cheek when he returned from work. Jay, stooping to receive his welcome, wore a farcical smile. At the dinner table, lavishly spread with high sauces and cheeses, lobsters, oysters and hot curries, Jay ate in greedy silence, speaking only to reprove his sons when an elbow sneaked indecorously onto the table. Supper concluded, Jay slipped upstairs to his room, donned his robe, and busied himself with his many hobbieshis bookplates, his elaborate puppet theater, the tiny matchbox houses he built, precise in every detail, and his vast collection of penny toys. His sons, forbidden to touch their fathers baubles, grew to loathe them. An artist must be pampered or he would not be an artist, says a character in one of Vivian Chamberss first short stories, written when he was seventeen.