Table of Contents

Lifeblood

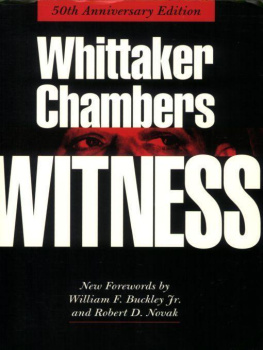

In 2006, Wall Street wizard and philanthropist Ray Chambers flicked through some holiday snapshots taken by his friend, development economist Jeffrey Sachs, and remarked on the placid beauty of a group of sleeping Malawian children.

Theyre not sleeping, Sachs told Chambers.

Theyre in malarious comas. A few days later, they were all dead.

So begins Chamberss race to eradicate a disease that has haunted humankind since Hippocrates, still infects half a billion people a year, and kills a million of them. The campaign draws in presidents, celebrities, scientists, and billions of dollars and becomes a stunning success, saving millions of lives and propelling Africa toward prosperity. By drawing heavily on business, Chambers also reinvents foreign aid, showing how helping can be both efficient and in all our interests.

As he follows two years of the campaign, awardwinning journalist Alex Perry takes the reader across the globe, from a terrifying visit to the most malarious town on earth to the White House, from the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo to soccers World Cup. In Lifeblood, Perry weaves together science and history with on-the-ground reporting and a searing expos of aid as he documents Chamberss frenetic campaign. The result is an incisive and often surprising portrait of modern Africa, a story of revolution in aid and development, and a thrilling and all-too-rare tale of humanitarian triumph, with profound implications for how to build a better world.

For Tess

They sprayed and sprayed till their eyes got sore

Then they refilled their machines and sprayed some more.

They worked most of the whole night through.

Killing mosquitoes for me and for you.

Their labors resulted in great success.

Of every one hundred mosquitoes, there were ninety-nine less.

But they were mocked and they were scorned,

Their heads with criticism were adorned.

What could be the problem then?

That such reward befell these men?

This answer is simple as numbers can be.

And the calculations reveal for all to see.

That if ninety-nine percent of one billion are slain.

Ten million of the devils still remain.

Matt Yates

President, American Mosquito Control Association

Malaria-free countries and malaria-endemic countries in phase of control*, pre-elimination, elimination and prevention of reintroduction, end 2008

Preface

Does aid work? As a journalist working in the developing worldfor three years in the Far East, five years in India, and now four more in AfricaI spend a lot of time trying to answer that question, and many hours sifting press releases from aid groups claiming heroic progress. I first heard about the malaria campaign in the usual way: an April 2009 email from a London PR executive, Rebecca Ladbury, asking whether I would be interested in writing about the launch of a new charity, Malaria No More UK. Ladbury explained the group had been jointly founded by Wall Street pioneer Ray Chambers, now UN Special Envoy for Malaria and Peter Chernin, then president of News Corporation. Chambers and Chernin had decided to apply their private sector expertise and considerable networks to tackle the worlds biggest solvable health crisis. After founding Malaria No More in the United States in 2006, they were broadening their scope, launching a British branch at a conference, held at Wilton Park in southern England, on malaria and efforts to fight it. The event was bringing together experts on the disease from all over the world.

The phrase solvable health crisis stood out. That meant, presumably, that Chambers and Chernin aimed to end malaria. Sure enough, the email went on to say that the two were part of a campaign that wanted to end malaria deaths in our lifetime. I called Ladbury.

Let me make sure Ive got this right, I said. Your clients are trying to kill malaria?

Right, said Ladbury.

That would save millions of lives, I said. It would be about the single biggest boost to health and development the world has ever seen. It would be astounding.

Right, repeated Ladbury, a little impatiently. Do you want me to set up some interviews?

I did. The ambition was breathtaking. Malaria was one of the worlds biggest diseases. It affected half the planet and killed a million people a year. But over the next three days, as Ladbury dragged ever more delegates to the telephone at Wilton Park to speak to me, I realized it wasnt just the campaigns aspiration that set it apart. There were religious leaders at Wilton Park. African health ministers. A smattering of celebrities. Business in particular appeared to be playing a central role: many of the people I was speaking to were senior managers at the worlds biggest corporations and talked about running their campaign as though it were a business.

When eventually I spoke to Chambers, he described fighting malaria in terms of efficiency, investment, and returns. His focus was to be as aggressive as possible to bring deaths as close to zero as possible. This was as much about economic cost as humanitarian cost, he added. Malaria costs Africa $30$40 billion each year, he said. Fixing it is in everyones interest. The key to that, he added, was a universal, global distribution of bed nets treated with insecticide. When the mosquito lands on the net, she dies. In areas where we have completed net distributions, deaths go down to zero. We can prevent this disease. This is the greatest opportunity any of us will have in our lifetimes. Its outstanding. And its doable.

Aid types normally didnt use words like aggressive or opportunity or even, much, doable. Malaria was traditionally viewed as a humanitarian concern. Chambers saw it equally as an economic one. My curiosity was piqued. And in the months that followed, I set out to track the campaign. I wanted to plot not only its progress but also its innovations. At first, I was simply pursuing a journalists hunch that this was a big story. Later, I was able to say why: it opened the door to a new way of aid.

Aid and development are increasingly mired in scandals over inefficiency and corruption, fueling a debate about whether such external assistance does any good at all. The malaria campaign was different in its fresh thinking, particularly the way in which it drew heavily from business. Its results were unusual too: Chambers said malaria was down by two-thirds in Zambia, by 60 percent in Rwanda, by half in Ethiopia, and by close to 100 percent on the Tanzanian island of Zanzibar. And as the months and years passed, during which I watched Chambers go to work in funding forums and aid conferences, and African hospitals and villages, I realized his campaign offered something extraordinary to the aid world: reinvention, even salvation.

There are thousands of people trying to defeat malaria, and it would take a very long book to mention them all. I am also aware that others involved in the work may feel, quite reasonably, that by focusing on Chambers and the group around him, I am denying them their due credit in the pages that follow. So let me be clear: this is not an attempt to document the entirety of the global campaign to kill malaria. Rather, this book tells the story of a small group of people who found themselves at the center of that campaign, whose new ideas and energy were crucial to its remarkable success, and who, I believe, have much to teach us about effective aid. By singling out Chambers and his team, however, I have no wish to downplay the role of others, and any offense is unintentional.