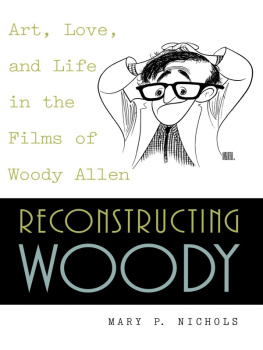

Marion Meade - Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography

Here you can read online Marion Meade - Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

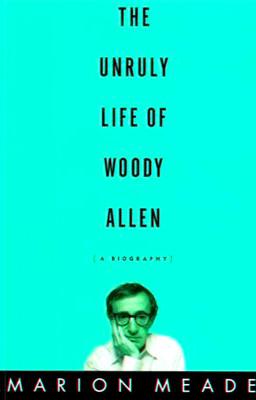

- Book:Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Unruly Life of Woody Allen

Marion Meade

For Katharine Rose Sprague

PROLOGUE

Grapes of Wrath

J ANUARY 13,1992

It was crazy weather for January. A sudden balmy spell swept a froth of showers and the fresh breezes of April into the city in the dead of winter. On Fifth Avenue, tangled morning traffic inched south toward the crosstown intersection at Seventy-second Street. Under a mottled gray sky, packs of MTA buses, white-and-blue, bunched in twos and threes, crept like a rare breed of tiger down the puddled asphalt of the Upper East Side, swerving royally past fortresses guarded by chandeliered lobbies and spiked gates (where you could buy a full-floor cooperative of eighteen rooms for $14 million); double-parked limousines studded with diplomatic license plates; and imperial-guard doormen all armed with glistening black umbrellas and silver whistles. On the side of every building was clearly posted the constitutional law of the land: ALL DELIVERIES MUST GO THROUGH SERVICE ENTRANCE.

Number 930 Fifth Avenue is a creamy-colored chunk of limestone and brick, its shiny steel-trimmed Art Deco canopy not facing Central Park but located around the corner on narrow East Seventy-fourth Street. The buildings shareholders live in big apartments with servants' quarters behind the kitchen and wood-burning fireplaces. More often than not, they own country houses. While 930 does not happen to be among the Avenues elite Social Register addressesthose dozen or so buildings considered white-gloveit is definitely blue-chip, and folks feel particular about their neighbors. They are partial to prospective buyers who maintain a modest profile, which is why entertainers with squealing fans never manage to make it past the co-op board.

Their most famous tenant is a man living in the duplex penthouse, whose double terraces afford a sweeping view of the parkthe Bethesda Fountain, the lake, and Strawberry Fields to the west. (The penthouse had been written up in Architectural Digest.) He had purchased the eight-room apartment twenty-two years earlier, just as he was achieving fame and fortune in films, after being hailed by one and all as a brilliant young stand-up comedian, the comics comic, and he had lived there in comfort for most of his adult life. In December he turned fifty-six. He still weighed 128 pounds, but his boyish physique had begun to show signs of wear, and he looked like a smaller, frailer version of himself. Even though he scorned face-lifts, as well as nip-and-tucks, his raggedy reddish hair was stabilized with transplants and dye and combed forward to make himself look youthful. He continued to sport the uniform of a sixties college student: cotton sport shirts, cashmere sweaters, khakis, and tweed jackets. To those who crossed his path in the lobby, he seemed uncommonly reserved. Some of his neighbors judged him a sweetheart who could always be counted on for generous donations to the block association. But to others he was a bit of a sourpuss.

The trouble was that he did not, on the whole, enjoy people very much. There were plenty of things he did appreciatethe New York Knicks, Groucho's gags, Mahler's Fourth Symphonybut he had never felt at ease around people (with some exceptions) or pets and animals (no exceptions). Riding the elevator up to his penthouse, he was known to face the wall like Greta Garbo or stick his nose in a paper to avoid conversation.

On this second Monday of January, after sleeping his usual seven hours, he woke up in his king-size, four-poster, canopy bed with a blue-calico spread. Outside his window, the skies were overcast and it was sprinkling. When the weather was gray and drizzly, he felt reassured that life would go on forever. Sunny days made him want to hide under the covers and think of dying.

A creature of habit, he seldom varied his early-morning routine of treadmill and shower, followed by having his regular breakfast of prune juice and Cheerios with raisins and sliced bananas as he read the New York Times. An article reported that he had attended a cocktail party on Friday night, after a private screening of a picture produced by his best friend, and that he sipped a lovely Pavilion Blanc du Chateau Margaux 1986. After finishing the Times, he practiced his clarinet for an hour and then departed for his editing office. Ordinarily, he breezed around the city in his black Mercedes sedan, or a rattling old station wagon, with his driver Don Harris behind the wheel. However, he preferred walking the thirteen blocks to his office at 575 Park Avenue, usually following the same route. At the intersection of Seventy-fourth Street and Madison Avenue, he headed south past Clyde Chemists, which delivers prescriptions to the luxury buildings on Fifth Avenue; past Ralph Laurens flagship store where he had shot scenes for Alice, notably the one in which an invisible Joe Mantegna sneaks into a changing booth with supermodel Elle Macpherson; past the plush Polo restaurant in the Westbury Hotela block of cherry-red awnings, where you could spend sixteen dollars on a half portion of fettuccine with fresh crepes, Swiss chard, and mushroom cream; and finally into the valley of the couture ghettothe houses of Gianni Versace, Giorgio Armani, Valentinobefore turning east to Park Avenue.

This morning, he was working on a new picture with his editor, Sandy Morse, who had been with him for fourteen movies. At present, the movie's working tide was "Woody Allen Fall Project '91," but eventually it would be called Husbands and Wives. Over the years constant experimentation had enabled him to devise an efficient method of working. He shot scenes in one or two setups; dispensed with close-ups and worked only in master shots; eliminated actors' rehearsals and allowed them to change dialogue; and seldom offered directionall shortcuts allowing him to finish a picture before he got sick to death of it. This time, the use of handheld-camera techniques and long takes running up to nine minutes permitted an even hastier shoot than usual. It was crude, off-the-cuff filmmaking that, in the hands of a less-confident artist, could have spelled amateur, but for him it meant principal photography could be completed ahead of schedule. With every picture, he started out with a strong idea. Unfortunately, however hard he tried, the original idea, gradually diluted along the way, never made it to the screen exactly as planned. Personally, he often said, he didn't care one way or the other what people thought of his films, just as he never saw his pictures after release and never read reviews. More and more, as he grew older, he thought of his work as self-therapy, a means, he said, of keeping busy "so I don't get depressed." But even before the reshoots, he felt good about "Woody Allen Fall Project '91," which was coming in under budget. Already in the pipeline was his next projecthis twenty-third filma murder mystery in which he would play an amateur detective. Shooting would begin in September.

Midway through the day, an assistant ordered takeout for him. It was his regular lunch, the same type of sandwich that he had eaten for the last forty-five yearstuna salad (or occasionally turkey for a change), no lettuce, no tomato, on healthful white bread, followed by a Nesde* Crunch bar or chocolate cake and coffee. On a typical winter evening, after leaving his office, he could be found at Madison Square Garden, watching the New York Knicks from his courtside seats behind the scorer's table. On Monday nights, he would head to his weekly concert at Michael's Pub on East Fifty-fifth Street, where he had been playing New Orleans jazz for more than two decades. Afterward, he would go home, get a bite to eat, usually chocolate-chip cookies washed down with two glasses of milk, and go to bed.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography»

Look at similar books to Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.