ALSO BY ERIC LAX

Radiation: What It Is, What You Need to Know

(with Robert Peter Gale, M.D.)

Faith, Interrupted

Conversations with Woody Allen

The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat

Bogart

(with A. M. Sperber)

Newman: A Celebration

Woody Allen, A Biography

Life and Death on 10 West

On Being Funny

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2017 by Eric Lax

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lax, Eric, author.

Title: Start to finish : Woody Allen and the art of moviemaking / by Eric Lax.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017002887 | ISBN 9780385352499 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385352505 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Allen, Woody, 1935 Criticism and interpretation.

Classification: LCC PN 1998.3. A 45 L 39 2017 | DDC 791.4302/33092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017002887

Ebook ISBN9780385352505

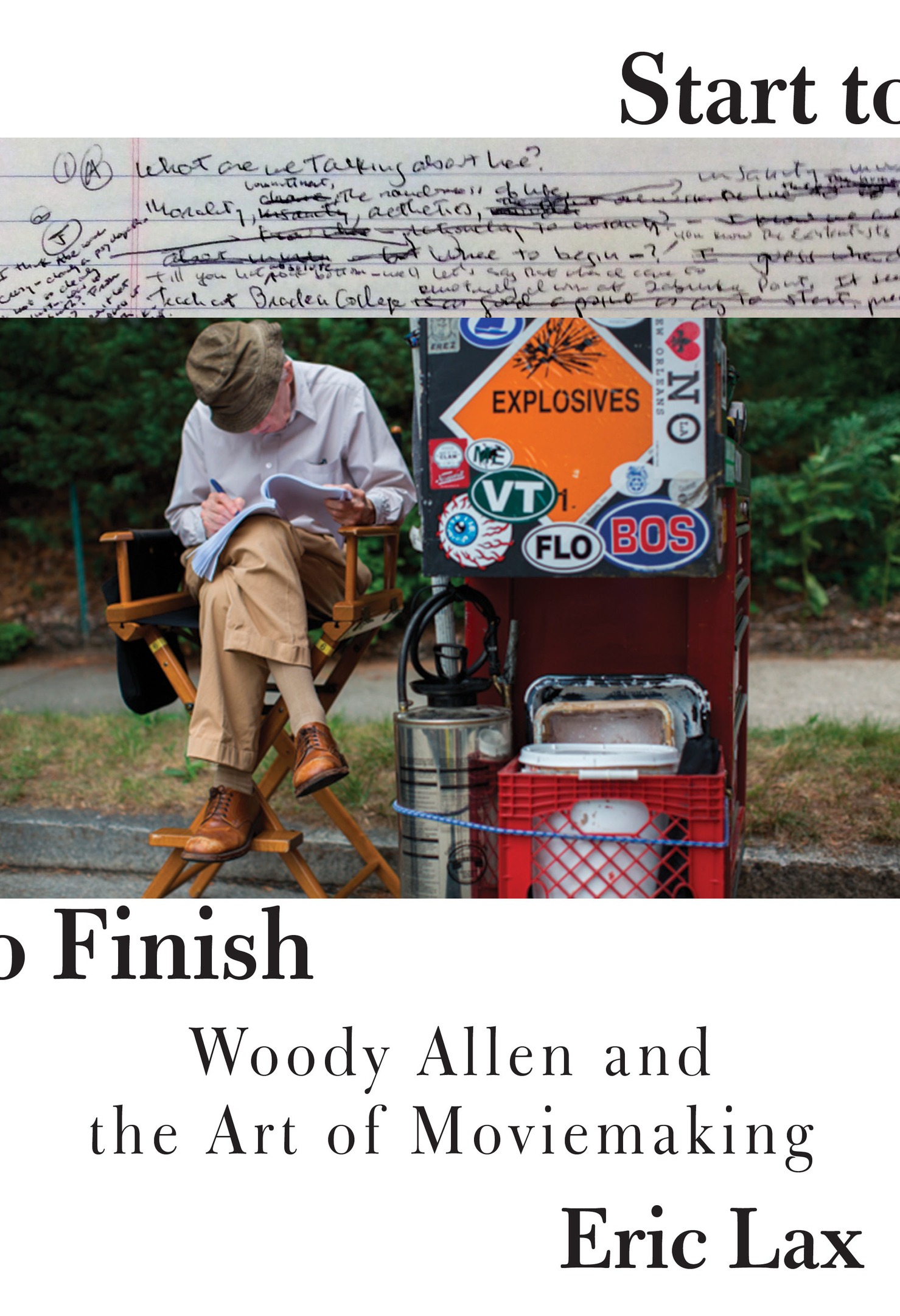

Cover photograph by Sabrina Lantos, copyright 2015 by Gravier Productions, Inc.

Cover design by Chip Kidd

v4.1

ep

Contents

For David Wolf and William Tyrer

Im offering up story all the time. That to me is what the movies are.

WOODY ALLEN

INTRODUCTION

W oody Allen has so far written and directed forty-seven theatrical films and acted in twenty-seven of them, an average of one a year since 1969, a continuous body of work unmatched in modern cinema. This does not include five films he wrote but did not direct; three he acted in but did not write or direct; one he wrote and acted in but did not direct; and the television movies and shows he has written and directed. Nor does it include Whats Up, Tiger Lily? (1966), in which his dubbed dialogue turns the Japanese adventure film International Secret Police: Key of Keys into the hunt for a top-secret egg salad recipe. Why he works at such a pace is individual to him; how he works and what he has learned from others is, I believe, instructive for anyone who cares about moviemaking.

The idea, the script, the money, the casting, the cinematographer, the locations, the production design, the costumes, the shooting, the editing, the music, the color correction, the mix: the movie. They come in many formsstudio pictures, indies made on shoestring budgets, niche films made for more, action franchises costing hundreds of millions. Star Wars or Stardust Memories,Harry Potter and the Sorcerers Stone or Deconstructing Harry, no matter the film or its maker, each required vision, determination, and organization to get made. Every filmmaker relies on a vital array of assisting talents. Part of Woodys uniqueness is the outstanding artistic contributors he has attracted and continues to attract to bring his vision to cinematic life. Along with a galaxy of great actors including Cate Blanchett, Michael Caine, Leonardo DiCaprio, Mia Farrow, Gene Hackman, Anthony Hopkins, Scarlett Johansson, Diane Keaton, Geraldine Page, Emma Stone, Charlize Theron, Max von Sydow, Dianne Wiest, and Kate Winslet, to name but a few, he has used the eyes of many of the worlds finest cinematographers, notably Gordon Willis, Sven Nykvist, Carlo Di Palma, Vilmos Zsigmond, Darius Khondji, and Vittorio Storaro. Santo Loquasto has provided brilliant production design for half his films, Juliet Taylor has overseen casting for nearly all of them, Helen Robin has kept production rolling for decades, Alisa Lepselter has edited the past nearly twenty films, and the other members of his crews are equally expert in their fields. He could not make his pictures without their valued contributions, but in the end, of course, each film is really his. He has had full control of every aspect of every one, beginning with Take the Money and Run (1969)even though he has writer/director/actor credits on Whats Up, Tiger Lily?, he considers Take the Money and Run his first fully theatrical movie. Unlike with almost every other director, the financing of his movies does not depend on their box-office appeal or the cast he selects. His ideas go from his head to the screen with no impediment between, his scripts unseen by his financiers and distributors. Shooting is over when he is done, regardless if that means exceeding the allotted days in the budget and giving back the cost from his fees. He is present for and decides the editing of every frame, chooses the music, oversees the color correction and the sound mix, and approves the ads that appear in New York (because those are the ones he sees).

Over the years there have been changes in how he makes a movie but few in how he writes one. Both because he has become more proficient and for budget constraints, he reshoots scenes far less often. Filming is fasterusually between thirty and thirty-five days instead of the eighty or more he sometimes needed in the past. He has become comfortable watching a scene unfold on a video monitor rather than observing it from beside the camera. He has taken to editing digitally and, as of 2015, to a digital camera in place of reels of film. His vision and his dedication, however, are unchanged. Now past eighty years of age, there has been no loss of drive or output by this deeply nuanced and singular artist.

By good fortune rather than design, I have been talking with him about his movies and moviemaking since 1971. In the decades since, I have watched him make more than a half-dozen films from the first day to the last and parts of more than twenty others.

His pictures and other projects flow so seamlessly from one to the next that they sometimes overlap. While this book has as its spine the making of Irrational Man, in the eighteen months that bookended it he also made Magic in the Moonlight, helped transform Bullets over Broadway into a Broadway musical, wrote Caf Society, and created Crisis in Six Scenes, a six-part series for Amazon that he later acted in and directed. We were in conversation throughout, talking in his home, in his screening room, on walks along Manhattans streets. I was with him all through the making of Irrational Man. He gave me access without restriction as he scouted locations, decided on costumes, and considered his casting. I sat by him as he worked and we talked between shots about what he was doing, was with him in the editing room for both Magic in the Moonlight and Irrational Man, and watched as he screened several versions of each. I was present for all I describe here, taking notes as he worked and of what he and others said. More than thirty hours of longer, more formal interviews were recorded. Unless otherwise noted, his quotes as he worked on other films during the past forty-six years are from our conversations at the time.

No two filmmakers work in an identical way; there is not a template that even slavishly adhered to guarantees a compelling movie. Craft is crucial but art is elusive. Copy every move of Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, Welles, Godard, Antonioni, Hitchcock, or Scorsese, and you might create a facsimile but not their work of genius. Yet brilliance often sparks innovation, and new art can emerge from observing how a master filmmaker proceeds.