Contents

Guide

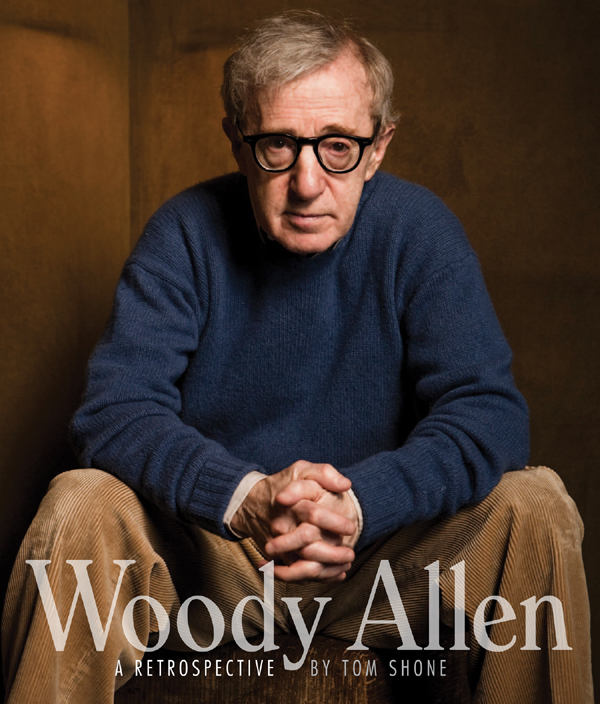

Woody Allen

A Retrospective

Tom Shone

INTRODUCTION

A creature of tidy habit and unerring routine, Woody Allen likes to rise every morning at 7 a.m. He practices his clarinet in his bedroom, putting on a Bunk Johnson record, say, and playing along with the band, before sitting down to write at his manual Olympia SM-3 typewriter, bought when he was sixteen and still working. Actually, his preferred writing position is not sitting but sprawling on the four-poster bed in his writing room, beneath a blue calico canopy, overseen on the bedside table by framed photographs of his idols Cole Porter, Sidney Bechet and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. If he is collaborating with another writer, he decamps to the living room. I would come over and for several hours a day we would work, recalled Douglas McGrath, his collaborator on Bullets Over Broadway. By four, our energies dipping, we slouched in our seats. It was with the sun setting that the outline of the West Side replaced my view of his eyes. I could tell what time it was by Woodys glasses.

Comedies usually take Allen about a month to write, dramas three months. Preproduction is similarly speedy, about two months, during which time his casting director, Juliet Taylor, will supply him with a long list of possible actors for each role. Casting calls are notoriously brief, with Allen usually trying to head the actors off at the threshold of the screening room before they can occupy a chair. You shouldnt be offended, Taylor will explain. He does this with everyone, And: This can be very brief. With pauses and a few cordial nods of the head, it can all be over in thirty seconds.

I did have the classic, three-minute conversation when he offered me the job, says Rachel McAdams, whom Allen cast in his 2011 film Midnight in Paris after seeing her in Wedding Crashers. He said, Well, if you dont want the job, well do something else some other time. I couldnt tell if he was offering me the job or giving me an out in case I didnt want it, which of course I did. I was very happy to be a part of his canon. Its funnyyou hear such ridiculous stories. He hates the color blue! Dont ever show up wearing blue! And I wear a very clearly blue shirt at one point. When the costume designer put it on me, I said, But he hates blue, what are you doing? Im just going to have to wear something else. Shes like, Well, this is a gray blue. And we debated over how blue the blue was and in the end Im sure he didnt notice that I was there that day.

A Woody Allen set is chaotic but quietso hushed, in fact, you would never guess that he was shooting a comedy. He doesnt yell Action! or Cut! himselfhis assistant director does it. Sometimes playing chess with the technicians between shots, Allen stands apart from his actors, watching, judging, mulling, and very occasionally making suggestions, mainly to encourage departures from the script. You know, I sit on the bed and write the dialogue, but the first thing Ill say to the actors is, Forget the script, Allen told me when I first interviewed him in the mid-1990s. He doesnt give a lot of direction, and he does give quite a lot of freedom, says McAdams. I kind of felt as if I was in the theater sometimes. He would set the stage, light this room quite beautifully and you could go anywhere in it, and pick up any prop; you could light a cigarette. He said, You know, if you think your character would do that, then give it a try.

Allen cuts within scenes as little as possible, preferring to construct them from longer master shots, sometimes handheld, sometimes not. Dont save your best stuff for the close-ups, Michael Caine advised actress Gena Rowlands after appearing in Hannah and Her Sisters. Hes not going to shoot any close-ups. Occasionally, he has replaced an actor when something is not working, as he did Michael Keaton in The Purple Rose of Cairo, but on the whole he is quicker to find fault with his script than with an actor, and always budgets for reshoots, sometimes of entirely new material: The second Thanksgiving dinner in Hannah and Her Sisters was just such a scene, written on the hoof when Allen realized he needed another dinner to balance the movie out. Filmmaking thus allows him much the same level of control as writing does, finding his way through to the finished work through successive drafts. He has the unusual luxury of second thoughts.

I like to have as much control as I can, he told me. Everybody has an instinct to control, because nobody wants to be at the mercy of life, of chance, of their boss, other people. And the trouble is that control slips away so quickly. The original deal that his agents Jack Rollins and Charles Joffe hammered out with United Artists all those years ago has needed some protectionin todays fractured cinematic landscape Allen has had to hustle, moving from Miramax to DreamWorks to Fox, like any other independent filmmakerbut the basics remain intact. He can make any film he wants to make, comic or serious, cast whoever he likes, reshoot what he wants to reshoot as long as he stays in the budget, control the ads, trailer, credits, musiceverything. Not since Charlie Chaplin has a comic artist been such a master of his own fate, although in truth it is Chaplin who does well out of the comparison. If Chaplin had survived the transition to sound, managed to evolve from comedian to dramatist, succeeded in replacing himself in his own films, putting them instead into orbit around a series of female characters whose voices he mastered with the same assurance as his own, expanded his filmmaking universe to feature ever more layered ensembles spanning a career that lasted fifty years as opposed to Chaplins twenty good years, then his achievement would merit comparison with Allens. Roll Chaplins oeuvre together with that of Preston Sturges, say, throw in the productivity of Ernst Lubitsch, plus the longevity of Billy Wilder, and you come close to Woody Allens achievement. From the vantage of this new century, he looks awfully close to being the most successful comic artist the medium has ever seen.

That assessment may come as a surprise to some, their view of him occluded by the clouds of media speculation surrounding his private life, while the quality of his films is subjected to the annual wine-tasting of criticsIs it a good Woody, or a bad Woody? being the first question asked of every new film. He has been pronounced the beneficiary of a comeback more times than seems logically possible. Allens very ubiquitya film a year for the best part of five decades, creating some forty-five films and countinghas conspired to keep his reputation hidden in plain sight, his sheer productivity a little exhausting to contemplate, his iconic status bringing its own form of invisibility. Hes just Woodythere, like a landmark building or tourist sight, but Allen is entirely absent, for example, from the pages of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskinds account of American cinemas last great golden age in the late 1960s and 1970s, when maverick directors like Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola, high on equal parts pot and French auteur theory, stormed the Hollywood citadel and produced one wild, ragged masterpiece after another, full of handheld camerawork, Godardian jump cuts, self-conscious narration and raw, improvised acting riffs that dared to question Americas headlong pursuit of the happy ending. But enough about