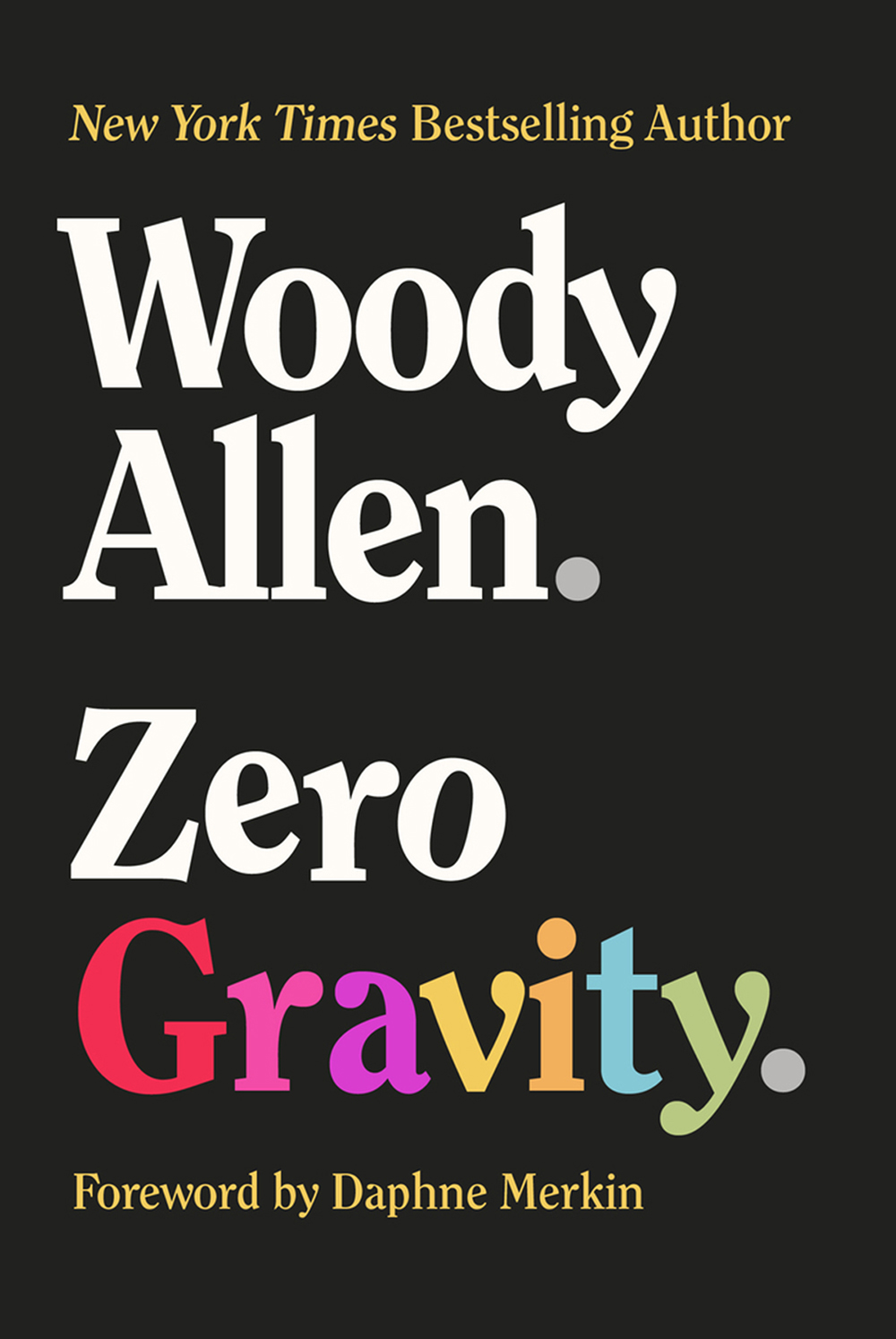

Copyright 2022 by Woody Allen

Foreword copyright 2022 by Daphne Merkin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First Edition

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022933864

Cover design by Brian Peterson

ISBN: 978-1-956763-29-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-956763-34-8

Printed in the United States of America

To Manzie and Bechet, our two lovely daughters who have grown up before our eyes and used our credit cards behind our backs.

And of course Soon-Yiif Bram Stoker had known you hed have had his sequel.

Contents

Foreword

by Daphne Merkin

ITS NO EASY matter being funny. As anyone knows whos stood around a cocktail party listening to someones lame jokes and having to laugh pallidly but politely in response, the wish to be funny looms large but is rarely granted. Being funny on the page, where timing and gestures and facial expressions cant be leaned on to punctuate or add emphasis to a quip, may be even more difficult. Once, in a time that seems far away, the art of being funny, of writing the sort of comic pieces that The New Yorker referred to as casuals, was practiced by such fleet-fingered greats as Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, George S. Kaufman, and S. J. Perelman. These days being funny, especially in print, seems, for the most part, to be a sweatier, more labored enterpriseproducing smiles of recognition, perhaps, but hardly chuckles or outright yelps of laughter.

And then theres Woody Allen. Many of his witticisms, whether from his essays or films, are embedded in our culture: If it turns out that there is a God the worst thing you can say about him is that hes basically an underachiever [ Love and Death ]. Others are less familiar but equally memorable, their effect based on an unexpected linkage of high-brow allusions and low-brow humor: I worked with Freud in Vienna. We broke over the concept of penis envy. Freud felt that it should be limited to women [ Zelig ]. One of my favorite lines is a send-up of the kind of portentous memoirist who assumes everyone is interested in his revelations and thus irritatingly tries to cover his tracks. The line comes from Selections from the Allen Notebooks, the first piece in Without Feathers , his second collection, published in 1975. (The first was Getting Even , published in 1971.) Should I marry W.? Not if she wont tell me the other letters in her name. A third collection, Side Effects , was published in 1980, and a fourth, Mere Anarchy , appeared in 2007.

There is also the fun made of Emily Dickinsons genteel observation, which functions as the epigraph of Without Feathers (Hope is the thing with feathers), which Allen painstakingly and hilariously corrects: How wrong Emily Dickinson was. Hope is not the thing with feathers. The thing with feathers has turned out to be my nephew. I must take him to a specialist in Zurich. Not to overlook the opening of Examining Psychic Phenomena: There is no question that there is an unseen world. The problem is, how far is it from midtown and how late is it open? Perhaps the most priceless piece in the book is The Whore of Mensa, about an eighteen-year-old Vassar student who doubles as a call girl. The madam she works for has a masters in comparative literature, and the eighteen-year-olds specialty is engaging clients in intellectual discourse. She can rattle on about Moby Dick (Symbolisms extra) and the lack of the substructure of pessimism in Paradise Lost . The piece is nothing short of ingeniousand side-splitting.

But one could go on and on. Without Feathers was published, hard as it is to believe, nearly half a century ago and spent four months on the New York Times bestseller list. It cemented Allens reputation as a cerebral jokester, an extension of the hapless, meek persona in his films but with an almost imperceptible shift away from his self-effacing nebbish yness to a figure with slightly (just slightly) more authority to comment on the preposterous world around him. There remained the characteristic undertone of melancholiawhat Allen himself has referred to as anhedonia (the inability to enjoy things)and the urban point of view, as well as the pessimistic outlook that partakes of the absurd and colors everything he lays eyes on, from love, sex, and death to the monuments of culture. In a section called Prognostication, again in Examining Psychic Phenomena, he quotes the ostensibly wise sayings of a sixteenth-century count called Aristonidis. I see a great person, this sage declaims, who one day will invent for mankind a garment to be worn over his trousers for protection while cooking. It will be called an abron or aprone. {Aristonidis meant the apron, of course.)

If comedians, as well as thirteen-year-old Asian pianists, can be said to be prodigies, then Allen certainly qualifies as one. He began selling jokes at fifteen and was bounced out of NYU because he played hooky a lot and didnt work or pay attention. A scant few years later, Allen was writing scripts for Sid Caesar specials, producing jokes at a rapid-fire pace. He worked with Mel Brooks, Larry Gelbart, Carl Reiner, and Neil Simon and could sit at his typewriter, as legend had it, for fifteen hours at a time, punching out wisecracks and witticisms. (No writers block here.) He went on during the sixties to perform as a standup comedian around Greenwich Village, at The Bitter End and Cafe Au Go Go. He also was writing and directing slapstick comedies, such as Take the Money and Run (1969), Bananas (1971), Sleeper (1973), and Love and Death (1975). I can still remember watching Take the Money and Run as a resistant, try-and-make-me-laugh adolescent and breaking into loud giggles when Allen, playing a foiled bank robber, holds up a sign saying, I have a gub.

And now, ladies and gentlemen and non-binary members of the reading public, your patience has been rewarded. The sad-eyed auteur has returned more than fifteen years since his last collection with a new volume called Zero Gravity . Some of the pieces have appeared in The New Yorker , and others have been written expressly for this volume. The latter include a poignant, fifty-page short story called Growing Up in Manhattan, which is quintessentially Allenesque in its mixture of romantic wistfulness and a raised-eyebrow air of disbelief at yet another contradiction in a world especially designed for him never to figure out.

Allens stand-in is twenty-two-year-old Jerry Sachs, who has grown up in Flatbush in a red-brick apartment building named after a patriot. The Ethan Allen. He thought a better name for the place given its grimy exterior, drab lobby, and drunken super, would be the Benedict Arnold. Sachs works in the mailroom of a theatrical agency, despite the wish of his mother, a perpetually charmless woman, that he become a pharmacist. The most revered member of his family is a cousin who enunciated like Abba Eban. Sachs lives in a crammed single-room walk-up on Thompson Street and annoys his wife Gladys (a perfect name for a first wife), who works at a real-estate office and attends City College at night to become a teacher, with his smorgasbord of psychosomatic complaints. He is enamored of Manhattan at its most glamorous, during the days of El Morocco and Ginos, when beautiful people exchanged bright dialogue and sipped cocktails on a Cedric Gibbons set.

Next page