A C ERTAIN C URVE OF H ORN

REVISED AND UPDATED E-BOOK EDITION

A C ERTAIN C URVE OF H ORN

T HE H UNDRED -Y EAR Q UEST FOR THE

G IANT S ABLE A NTELOPE OF A NGOLA

J OHN F REDERICK W ALKER

Copyright 2002, 2011 by John Frederick Walker

Epilogue 2004, 2011 by John Frederick Walker

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Walker, John Frederick.

A certain curve of horn : the hundred-year quest for the giant sable antelope of Angola / John Frederick Walker.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9442-8

1. Sable antelopeAngola. 2. Antelope huntingAfrica

History. 3. AngolaDescription and travel. I. Title.

QL 737.U53 W26 2002

599.645dc21 2002066576

DESIGN BY LAURA HAMMOND HOUGH

Grove Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

FOR E LIN AND G AVIN

C ONTENTS

W E CARRY WITH US THE WONDERS WE SEEK WITHOUT US :

THERE IS ALL A FRICA AND HER PRODIGIES IN US .

Sir Thomas Browne

P ROLOGUE

October 18, 1999, south of Luanda, Angola

I should step back from the crumbling edge of this sea-clawed cliffa sheared-off face of red sand that could give way and send me and my brief regrets to the rock-slapping waves below. But Im hoping to see something from this height. The afternoon sun, half-lidded by leaden cloud banks, is surprisingly strong and the broken light glinting on the gray ocean makes me squint. Then I see it, the sand-barred mouth of the Cuanza River gaping out from the eroded African coastline to the north, and follow its curving course inland until it disappears into the interior war zone.

Why am I standing on this half-eaten hill? Because of a mysterious animal I first came across in a book. I was a small boy then, but that chance moment made me wonder what it would be like to go to Africa and search for the beast. That vague and fleeting daydream has grown into a determination to know the animals fate. The answer lies far down the dark Cuanza, deep in the miombo forest, where two rivers join to embrace the no mans land no naturalist has dared visit for almost twenty years, the realm of the antelope the Angolans call the palanca preta (or negra) gigante.

I have yet to see a living one. But in anticipation, Ive burnished an image of the animal in my mind and carefully placed it in the same imagined scene over and over again. It is in a dark, leafy forest where blotches of sunlight quiver in torn patterns on the ground, mimicking the sparse canopy of branches and leaves above, hidden by a screen of underbrush at the edge of the woods. Fingers of light jab through the lattice of tree trunks to pick out a ripple of black fur, the gleam of a dark eye.

Then the scene comes to life, and an antelope the size of a small, heavily muscled horse steps out of the shadows into the morning sun. He is a master bull, the very monarch of his tribe. His glossy, grackle-black fur seems even darker in contrast to the bright white underbelly and inner legs and the white stripes that streak his slim, equine face like tribal markings. A shaggy, upright black mane crests his thick neck and powerful shoulders. And crowning all, a pair of colossal knurled horns that rise straight up above the eyes and sweep back in gleaming five-foot-long arcs ending in points as smooth and sharp as awls, thick-shafted curved spears streaked red from the animals habit of stropping them on trees until the trunks are flayed bare of bark and run with crimson sap.

As the beast struts out, a dry-season panorama of a grassy clearing unfolds before him on which a dozen smaller, chestnut-colored, more modestly horned cows graze near several four-foot-high termite mounds. Several young calves nervously dart in among them, nibble at the soft grass, lie down, and then jump up again. The bull ignores the herd, but scans the edge of the forest for potential rivals prowling for straying females. Forefeet planted on the edge of a termite mound to survey his surroundings, hind feet stretched out behind, he stands stock-still, posing, as if he knows he is a living masterpiece. Arrogant and aggressive, he finds little in his natural world to fear. Few predatorseven wild dogs or leopardswill readily risk the sword-swipe of his horns. Satisfied no challenges lurk, he lowers his heavy head to nip some tender shoots.

What is this creature that stalks my imagination? He is a superlative specimen of Hippotragus niger variani, the royal, or giant, sable antelope, the last great quadruped of Africa to be brought to the worlds notice. That was in 1916, when two pairs of skulls and head-skins, given to the British Natural History Museum by H. F. Varian, the chief engineer supervising construction of a railway across the Portuguese West African colony of Angola, were recognized as evidence of a previously unknown subspeciesand the most majestic antelope in all of Africa.

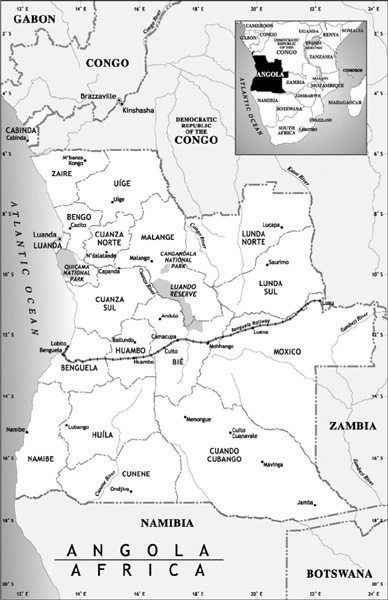

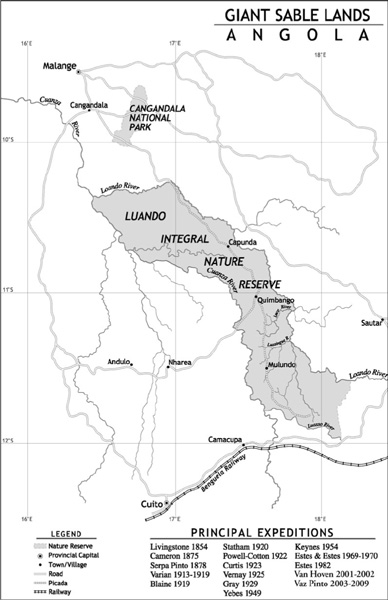

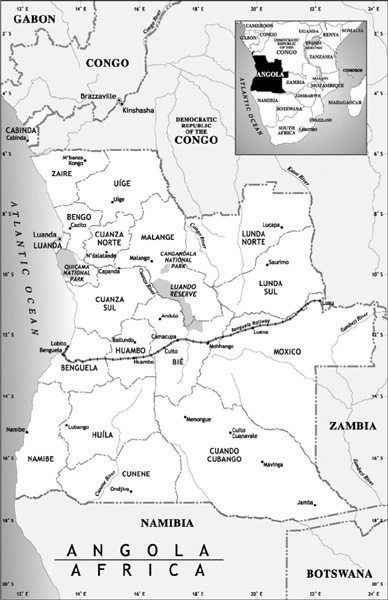

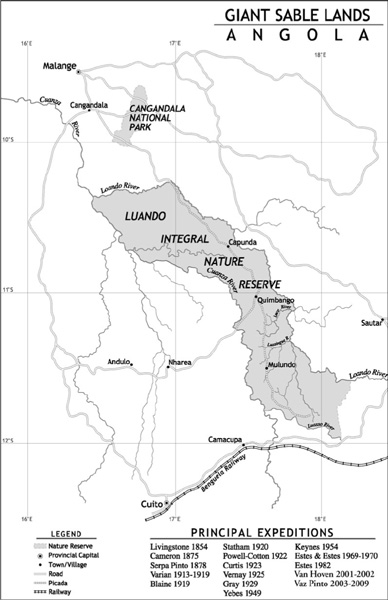

You can find the known range of the giant sable easily enough on a map of Africa by putting a finger at the point where the equator starts to cut across the continent at Gabon on the Atlantic and then following the coastline down past the mouth of the Congo River into Angola. Just above ten degrees latitude, cupped in the calm waters of the Baa do Bengo, lies the capital, Luanda. Just south of the city, below the swelling coastline, the wide Cuanza reaches the ocean. Trace that meandering river inland, first eastwardacross a country larger than France, Spain, and Portugal combinedthen southeast through the rugged highlands until you reach the elevated plateau in the very heart of the country. Find the twisted territory between the upper Cuanza and its tributary, the Luando. Keep your finger there, and look for a much smaller area just north and to the east of Cangandala, southeast of the city of Malange. These are the only lands where Africas greatest antelope exists, in a precarious population that as far as anyone knows has never numbered more than two thousand and has often dipped to just several hundred.

In English, royal or giant rightly implies that the animal is the supreme example of its kind, far grander than the common (if one can call them that) sable antelope found in fair numbers elsewhere across Africas southern savanna, but says nothing about the sacred status of this creature among the Lwimbi and Songo peoples who have long shared its realm. The fact that both tribes have often denied its existence to outsiders and misled foreign hunters makes it clear that the great dark antelope

Next page