A LSO BY THE AUTHOR:

Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the

American Press and Radio in World War II

From the Front: The Story of War Featuring

Correspondents Chronicles

On the Move: Transportation and the American Story

Return to Titanic

The Military and the Press: An Uneasy Truce

(Medill School of Journalism Visions of the American Press)

God Grew Tired of Us: A Memoir

Last Unspoiled Place: Exploring Utahs Logan Canyon

Peace: The Biography of a Symbol

National Geographic Complete Survival Manual

Brain: The Complete Mind: How It Develops, How It Works, and How to Keep It Sharp

Dog Tips From DogTown:

A Relationship Manual for You and Your Dog

Brainworks: The Mind-bending Science of How You See, What You Think, and Who You Are

Dr. Michael S. Sweeney is a professor at Ohio Universitys E.W. Scripps School of Journalism, where he serves as director of the graduate program and teaches print journalism courses.

He has written a variety of books for National Geographic Books, including God Grew Tired of Us, Brain: The Complete Mind, and BrainWorks. He also has published academically on the history of wartime journalism, and particularly on the methods and effectiveness of censorship in wartime. His first book, Secrets of Victory, about the American Office of Censorship in World War II, was named book of the year for 2001 by the American Journalism Historians Association.

He is associate editor of Journalism History, a quarterly academic journal published at the Scripps School.

Dr. Sweeney received his bachelors degree from the University of Nebraska, his masters from the University of North Texas, and his Ph.D. from Ohio University.

He lives in Athens, Ohio, with his wife, Carolyn.

(Author photo by Carolyn Sweeney)

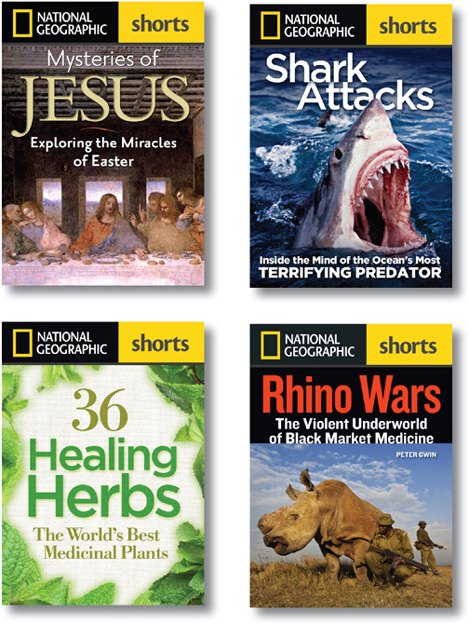

Discover More NG shorts

Quick Takes on Hot Topics for Todays Busy Ebook Readers

AVAILABLE WHEREVER EBOOKS ARE SOLD

Find us on facebook.com/NatGeoBooks

DIVE DEEPER INTO THE SECRETS OF THE WORLD'S MOST TRAGIC SHIPWRECK

With the National Geographic Channel, Magazines, Books, Maps, DVDs, Games, Teaching Tools, and More

www.natgeotv.com/titanic

C HAPTER 1

The Tragedy

having great magnitude, force, or power: COLOSSAL

Definition of titanic, Merriam-Websters Collegiate Dictionary

U ntil an icy night a hundred years ago, the word titanic suggested good things. Godlike Titans ruled a golden age of Greek mythology. Titanic meant big, powerful, extraordinary.

That changed on April 14-15, 1912, as the Royal Mail Ship Titanic, the worlds largest and most opulent oceangoing vessel, steamed westward on its maiden voyage. About 1,000 miles east of Boston, it struck an iceberg and disappeared in 2 hours and 40 minutes. More than 1,500 passengers and crew died, including some of the grandest celebrities of the day.

A rescue ship, Carpathia, plucked 706 survivors from lifeboats. Their stories of the tragedy seemed impossible.

Sink? How could it? At 882.5 feet from prow to stern rail, and 175 feet from keel to funnel tops, Titanic stretched as long as four city blocks and as high as a nine-story building. Fifteen steel bulkheads divided its interior into compartments advertised as watertight. Titanics builders figured it could stay afloat after any possible accident.

Sink? In the previous 40 years of North Atlantic travel, only four passengers had died. Disasters had become obsolete.

Sink? Even Titanics captain once announced he could envision no scenario in which a modern ship might go down.

Shipbuilder magazine had examined Titanic and pronounced it virtually unsinkable. Over time, the adverb evaporated.

And yet sink it did, in a perfect storm of human error and hubris. Like the Titans themselves, the word was Greek. It meant extreme pride or arrogance. Never again after April 1912 would humanity feel so smug.

Hubris inserted itself into Titanics story at the ships conception. That occurred over Napoleon brandy and Cuban cigars in the London home of Lord Pirrie on a summer night in 1907.

Enjoying their drinks and smokes were J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, and Lord Pirrie, chairman of the shipbuilding company Harland & Wolff. White Star had amassed a fortune ferrying emigrants to America as well as shuttling wealthy passengers across the Atlantic.

But White Star had competition. Rivals sought to build faster, more comfortable ships. American and German lines fought for control against British counterparts, including Cunard. In 1906 and 1907, Cunard introduced Lusitania and Mauretania, two passenger ships that seemed the last word in speed and luxury.

Ismay refused to be outdone. He wanted Harland & Wolff to build White Star a fleet of ships that would dwarf the competition. So, while relaxing after dinner, Lord Pirrie sketched the ships Ismay wanted.

There would be three, all alike. They would be 120 feet longer and 12,000 tons heavier than Cunards biggest. They would have three-story engines fired by 29 coal-burning boilers. Their lines would be elegant, their capacity astounding, their safety beyond question. First to be built would be Olympic, followed by Titanic, then Gigantic (later renamed Britannic).

More than 15,000 workers teemed through the Harland & Wolff gates in Belfast, Ireland, every morning to produce ships of iron and steel. They laid Titanics keel on March 31, 1909, next to that of its twin, Olympic. Over the next two years, about 3,000 workers devoted themselves to Titanic. They riveted overlapping steel plates to shape the hull and prepared the shell for its decks.

Thomas Andrews, Harland & Wolffs chief designer, supervised construction. He felt proud of his work. On a night in 1910, Andrews brought his pregnant wife to the shipyard to show off his other children, Olympic and Titanic. Halleys comet blazed overhead.

Launch day, May 31, 1911, broke clear and bright. Lord Pirrie, Ismay, and American millionaire J. P. Morgan, who had acquired financial control of White Star, joined a crowd of about 100,000 to watch Titanic slide into the River Lagan on greased wooden skids. Support poles fell away. Lord Pirrie gave a signal to release the final restraints, and Titanic moved for the first time. Overhead, signal flags on the gantry spelled Good Luck.

Titanic floated, but only as skeleton and skin. The process of fitting out required nearly a year. It included framing and furnishing rooms, raising four funnels, and doing everything necessary to prepare for sailing.

Not a shilling was spared. Titanic boasted a heated swimming pool, Turkish bath, cafs with palm trees, a First Class dining saloon that could seat 554, a gymnasium, a squash court, and a Marconi radio room intended not only to send safety messages at sea but also to please rich passengers who wanted to communicate with the shore.