THE TITANIC

KEY INFORMATION

When: On the night of 14th-15th April 1912

Where: In the Northwest Atlantic

Context: The Belle poque (the era of liner ships)

Main actors:

Edward John Smith, British sailor (1850-1912)

Thomas Andrews, British naval architect (1873-1912)

Joseph Bruce Ismay, British businessman (1862-1937)

Repercussions:

New legislation on maritime safety

The creation of the International Ice Patrol

The birth of a myth surrounding the Titanic

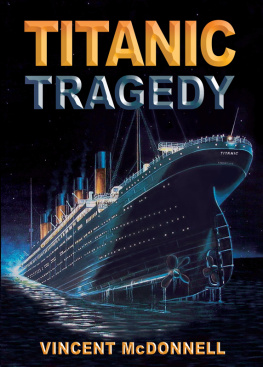

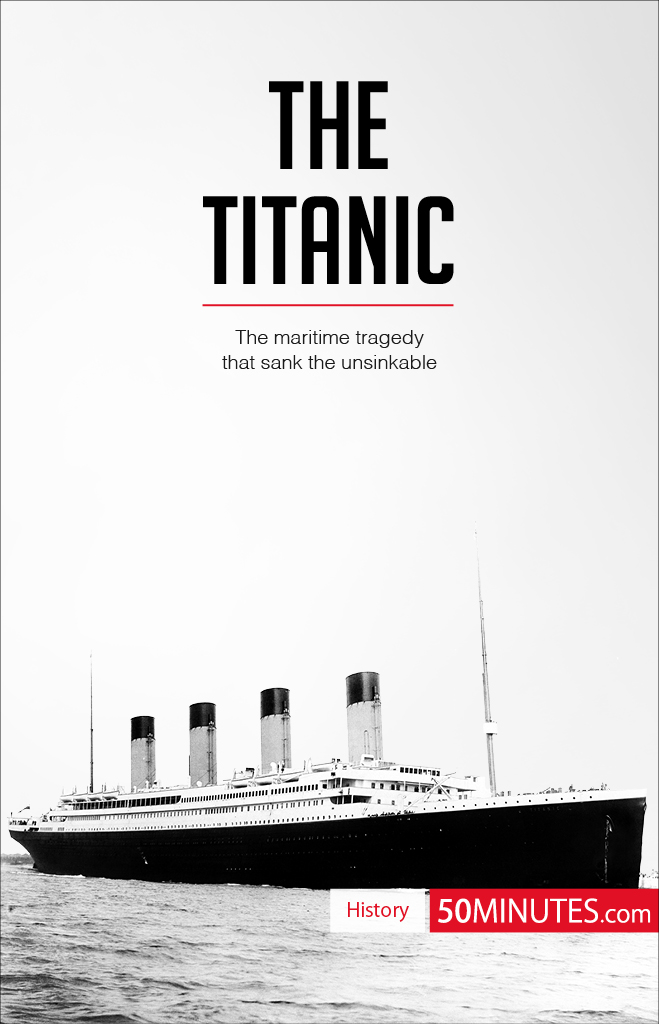

Gigantic, luxurious, beautiful, unsinkable; ever since its creation, the Titanic has been the subject of the most beautiful descriptions. For travelers of the early 20th century, there was no doubt about it: the ship, a masterpiece of its industry, was indeed the largest liner in the world. The jewel of the shipping company White Star Line, the Titanic was designed, through its luxuriousness and more advanced technology, to far outshine the ships of rival companies in the transatlantic crossing, which connected the Old Continent to New York.

On 10th April 1912, the ship began its maiden voyage, under the command of Edward John Smith, a veteran of the seas who had great confidence in the ships abilities. 2200 passengers and crew members were onboard, including some of the biggest celebrities of the time. They all anticipated taking the journey of their dreams, unaware that the prestigious ship was doomed.

On 14th April 1912, sailing at an ever increasing speed, the Titanic headed towards a zone of drifting ice. Although messages of caution continued to warn of the danger looming on the horizon, none of them were really taken into account. But, at 11:40pm, lookouts noticed that the ship was racing towards an iceberg. Despite the quick response of the crew, the starboard side of the Titanic struck the ice. The damage was heavy and there were only 1178 seats available in the lifeboats. One of the worst maritime tragedies in history was about to take place.

CONTEXT

EUROPE: MASTER OF THE WORLD

The Titanic alone certainly could not summarize the context of its time. Nevertheless, many similarities can be drawn between the fate of the luxury liner and the coming doom of European society, which was about to be destroyed by the iceberg that was the Great War (1914-1918). Like the ship, the Europe of the late 19th century and early 20th century really was the master of the world. Within a few decades (1830-1870), its economy had been transformed forever by the first industrial revolution (iron, coal and the steam engine). As the first was so successful, a second revolution inaugurating the era of oil, steel and electricity began in 1896. Capitalism became king on the Old Continent, which, following these great changes, saw its population double in just 50 years.

This incredible economic and population growth led Europe to turn to the rest of the world. Indeed, the Old Continent no longer had the food resources or the raw materials needed for its growth. Therefore, it was essential to seek new markets that would provide it with resources, but also consumers. This context thus opened Europe to colonialism and imperialism. Africa and Asia were the victims of this new colonization, which saw the European powers arguing over each plot of land. In 1900, the Old Continent truly dominated the world with its colonies, so much so that one in four people in the world lived in a territory belonging to Britain. Only the United States and Japan managed to escape this hegemony.

After this process of expansion, Europe submitted the rest of the world by imposing its values, its policies and its industry. To the detriment of the colonized peoples, it monopolized all the wealth and redistributed its products, inexorably increasing its own profits. The world was now organized by Europe and for Europe. However, the continuous search for riches created inequalities and divisions between the European nations, to the point where a war seemed inevitable.

THE EFFERVESCENCE OF THE BELLE POQUE

Driven by the innovations in energy and technology, the various industrialized countries were developing a culture of progress in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, encouraging inventors and engineers to constantly push the limits of possibility. The men of the Belle poque showed unrivaled optimism towards science and technology, which, with each step forward, enhanced everyday life for an even brighter future.

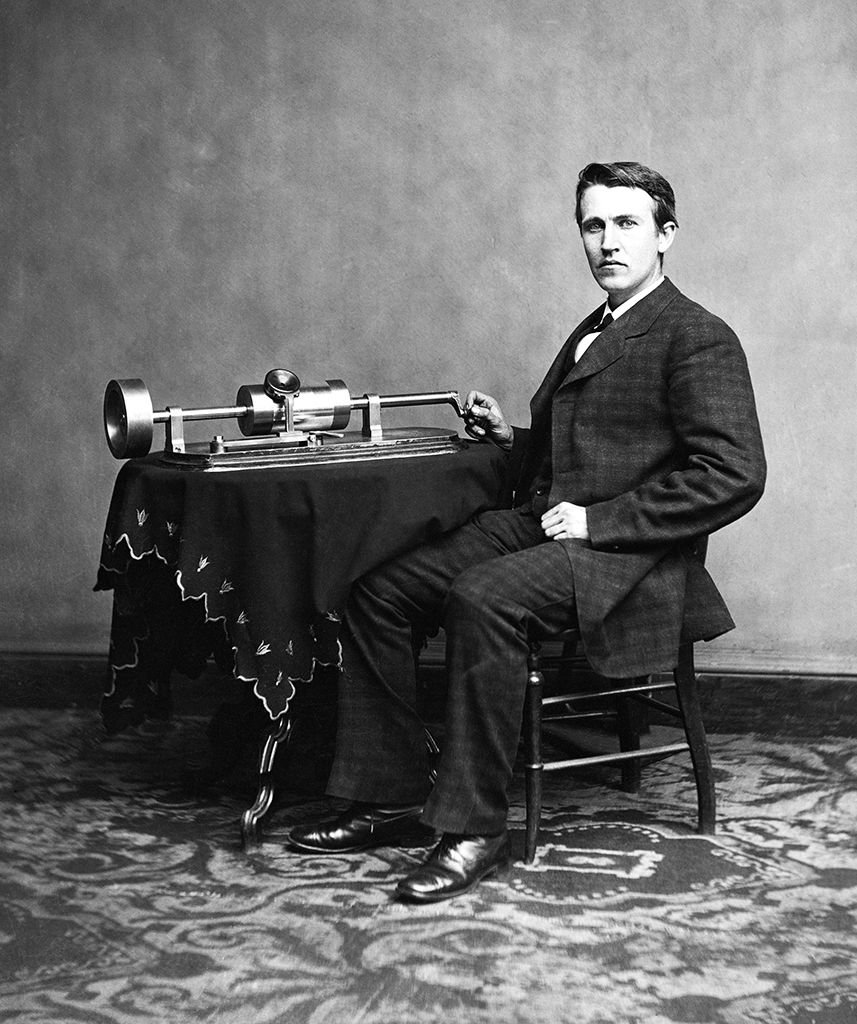

The electricity fairy, created by the invention of the incandescent light bulb by Thomas Edison (American inventor, 1847-1931) in 1879, made its appearance in the big cities, accompanied by the dynamo and even Telecoms without Borders (TSF). Similarly, the first household appliances, such as electric polishers, or the first telephones by Graham Bell (American inventor and physicist, 1847-1922) emerged in the late 19th century. The art of entertainment was no exception, with the invention of the phonograph and the cinema. Finally, science in general, particularly medicine, made great progress with the theory of relativity of Albert Einstein (American physicist, 1879-1955), discoveries on radioactivity by Marie Curie (French physicist, 1867-1934) and in the field of X-rays and pharmaceuticals. Hygiene became essential for medicine, and the use of chloroform now allowed for general anesthesia.

Thomas Edison and his photographer, 1878.

Therefore, all areas of society underwent changes thanks to the progress of the Belle poque. However, there was one specific phenomenon to which all energy sources would contribute: the abolition of distance.

THE GLORY DAYS OF LINER SHIPS

In this buzzing world, engineers competed to create ever faster transport, with maximum capacity. Indeed, the incredible economic growth of the 19th century pushed manufacturers to send goods, but also information and men around the world as quickly as possible. From the 1830s, the railway network was extended to link even the most remote of regions. Trams then took over in cities that had electricity. The car also appeared at the end of the century, and with the invention of the assembly line, symbolized by the Ford Model T of industrialist Henry Ford (1863-1947), it became one of the first objects of mass consumption. Finally, aviation was in its infancy with the invention of the motorized airplane by the brothers Orville Wright (1871-1948) and Wilbur Wright (1867-1912).

Ford Model T, 1910.

However, these means of transport were not yet sufficiently developed to connect the four corners of the world. In this area, the sea remained the most effective. The great clippers with sails had now been succeeded by huge ships that were capable of carrying thousands of goods and passengers whether wealthy, servants of simple immigrants. A symbol of industrial strength, the liners were also the result of a fierce rivalry between businessmen, aiming to produce the most luxurious, largest and fastest ships. An award known as the blue ribbon was even awarded to the fastest ship, proof of the competition being waged by ship-owners. In the first half of the 19th century, the first shipping companies opened up the transatlantic route, with the most prestigious being none other than the line connecting the Old Continent with New York. In the early 20th century, no fewer than 150 ships ensured this junction. With a length of up to 200 meters, their speed now reached 23 knots (about 40km per hour), reducing the crossing to just six days.