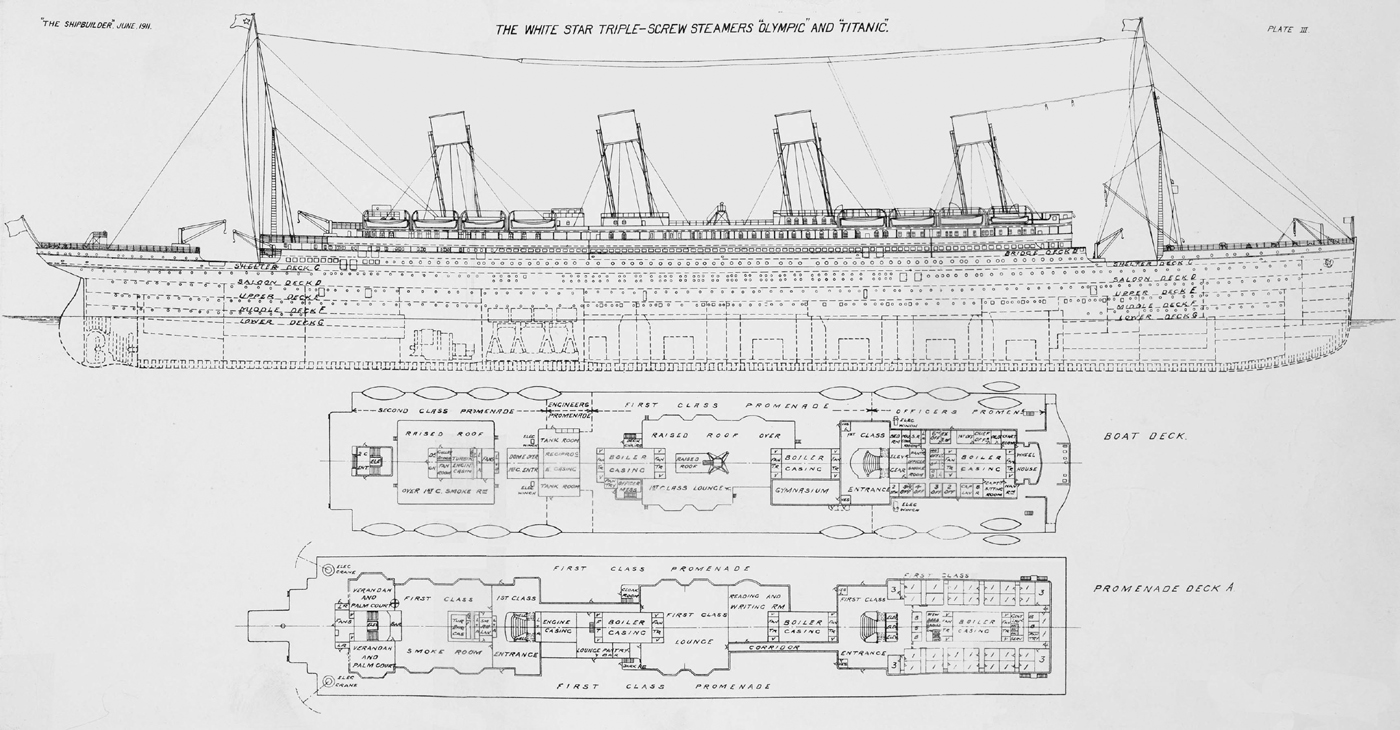

Plan of Olympic and Titanic. SSPL via Getty Images

Harland & Wolff hull-drawing office. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Gantry over the building berth for Titanic and Olympic. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Shipyard workers disembarking from Olympic. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Captain Smith and Lore Pirrie on Olympic,1911. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Lord Pirrie and Bruce Ismay inspecting the hull. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Titanic being escorted by tugs through Belfast Lough. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Titanic pulling away from White Star dock, Southampton. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

First-class Caf Parisien on B Deck, March 1912. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

First class parlour suite B59, March 1912. National Museums Northern Ireland / Collection Harland & Wolff, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

Crowds waiting to embark at White Star Wharf, Queenstown. The Irish Picture Library / Father FM Browne SJ Collection

Murdoch and Lightoller seen from the tender at Queenstown, 11 April 1912. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Looking up from the tender, with Captain Smith and passengers gazing down. The Irish Picture Library / Father FM Browne SJ Collection

Titanic's first-class gymnasium. The Irish Picture Library / Father FM Browne SJ Collection

The promenade deck. The Irish Picture Library / Father FM Browne SJ Collection

Second-class passengers on the boat deck. Irish examiner

Lifeboat 14 under Lowe towing Collapsible D. Courtesy Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Crowds outside White Star offices. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Survivor Samuel Rule talking to his brother at Plymouth. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Able seaman Horswill, possibly with a cheque for Lifeboat 1. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Crew arrive at Southampton, April 29. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

White Star company men enter St Mary's Church. Southampton City Council, Arts & Heritage

Corpse of a Titanic victim onboard rescue vessel Minia. Courtesy Nova Scotia Archives

From Greenlands Icy Mountains

Its most striking feature was the stillness and deadness and impassability of this new world: ice, and rock, and water surrounded us; not a sound of any kind interrupted the silence; the sea did not break upon the shore; no bird or any living thing was visible; the midnight sun by this time muffled in a transparent mist shed an awful, mysterious lustre on glacier and mountain; no atom of vegetation gave token of the earths vitality; a universal numbness and dumbness seemed to pervade the solitude.

Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, Letters from High Latitudes

There were no witnesses. It didnt look like a moment from history. A great block of ice broke off the end of a glacier, and crashed down into a fjord with a rumbling roar. Probably it was the Jakobshavn glacier, the source of most of the worlds largest icebergs. A hundred years ago Jakobshavn was the fastest-moving glacier in the world, pushing down from the ice cap at the rate of 65 feet a day, until it reached the west coast of Greenland. About 10 per cent of all Greenland icebergs have split or calved from the end of Jakobshavn. After they have wrenched away from the glacier, itself made of densely compacted snow which fell on the Arctic ice cap thousands of years earlier, icebergs rock and tilt on the water until finally they settle into balance.

Although there is a human settlement at Jakobshavn, Greenland is an inhuman landscape of neverending wastes. One cannot hope for mercy from the elements in this savage land of lifeless gloom. Long, dark, freezing winters are followed by brief, colourful summers so bright that Matthew Henson, the black American who accompanied Robert Peary to the North Pole in 1909, found summer midnight in Greenlands ice-bound wilderness as bright as dusk in New York on the 4th of July. The land belongs to polar bears, reindeer, musk oxen, wolves, arctic foxes and mountain hares. White-tailed eagles rule the skies, especially near Cape Farewell; black ravens are ubiquitous with their croaking; guillemots and ptarmigans are hunted as food; stiff-winged gliding petrels, snow buntings and peregrine falcons abound. There are fish, and walruses, but until recently no pleasure-seekers in the fjord. In such a wilderness of primeval rocks and eternal ice was launched the iceberg that made history.

Since 2000 the tongue of Jakobshavn glacier has retreated at an alarming rate from the coast, and the ice flow behind has sped up. Jakobshavn, indeed, is one of the great loci of global crisis. Nowadays 35 billion tonnes of iceberg calve from the glacier each year and float oceanwards down the fjord. Only about one-eighth of an iceberg is visible above water: the submerged seven-eighths can be so deep that icebergs get wedged on the floor of the fjord, and remain jammed there until broken by the weight of other icebergs smashing onto them from the glacier. As they are largely submerged, the drift of icebergs is governed by current and little affected by wind.

Some icebergs from Iceland are carried by the east Greenland current round Cape Farewell, where they join thousands of other icebergs from the western glaciers and together sweep into Baffin Bay. There they are taken by the Labrador Current, which carries them southwards towards the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Many icebergs run aground on the coast of Labrador or on the northern part of the Banks and there disintegrate. The first appear near the Grand Banks about the beginning of March cold monsters that are so beautiful to look at and so dangerous to touch, in the words of a Cunard captain on the North Atlantic run.1 By the end of June they have ceased. During a normal year some 300 to 350 icebergs drift south of Newfoundland, and about fifty are borne south of the Grand Banks. Short of bombardment there is no means to destroy an iceberg except by waiting for it to melt. The largest of them drift 2,500 miles before they dwindle away in the sun around Latitude 40. From the bridge of a liner on a clear day a large iceberg can be seen at 16 to 20 miles distance. In bright sunshine it appears as a luminous white mass. In dense fog its sombre bulk is undetectable at more than a hundred yards. On a fogless night without a moon an iceberg would be visible at a quarter of a mile, but in moonlight it might be seen at a distance of several miles.