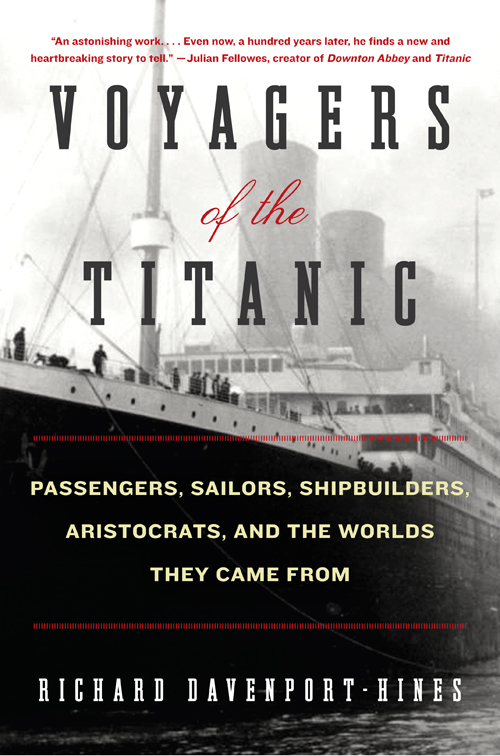

Voyagers of the Titanic

Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came From

Richard Davenport-Hines

For Patric Dickinson and David Kynaston

and for the gentle memory of Cosmo Davenport-Hines

Contents

From Greenlands Icy Mountains

Its most striking feature was the stillnessand deadnessand impassability of this new world: ice, and rock, and water surrounded us; not a sound of any kind interrupted the silence; the sea did not break upon the shore; no bird or any living thing was visible; the midnight sunby this time muffled in a transparent mistshed an awful, mysterious lustre on glacier and mountain; no atom of vegetation gave token of the earths vitality; a universal numbness and dumbness seemed to pervade the solitude.

M ARQUESS OF D UFFERIN AND A VA, L ETTERS FROM H IGH L ATITUDES

T here were no witnesses. It didnt look like a moment from history. A great block of ice broke off the end of a glacier and crashed down into a fjord with a rumbling roar. Probably it was the Jakobshavn Glacier, the source of most of the worlds largest icebergs. A hundred years ago Jakobshavn was the fastest-moving glacier in the world, pushing down from the ice cap at the rate of sixty-five feet a day until it reached the west coast of Greenland. About 10 percent of all Greenland icebergs have splitor calvedfrom the end of Jakobshavn. After they have wrenched away from the glacier, itself made of densely compacted snow that fell on the Arctic ice cap thousands of years earlier, icebergs rock and tilt on the water until finally they settle into balance.

Although there is a human settlement at Jakobshavn, Greenland is an inhuman landscape of never-ending wastes. One cannot hope for mercy from the elements in this savage land of lifeless gloom. Long, dark, freezing winters are followed by brief, colorful summersso bright that Matthew Henson, the black American who accompanied Robert Peary to the North Pole in 1909, found summer midnight in Greenlands icebound wilderness as bright as dusk in New York on the Fourth of July. The land belongs to polar bears, reindeer, musk oxen, wolves, arctic foxes, and mountain hares. White-tailed eagles rule the skies, especially near Cape Farewell; black ravens are ubiquitous with their croaking; guillemots and ptarmigans are hunted as food; stiff-winged gliding petrels, snow buntings, and peregrine falcons abound. There are fish and walruses, but until recently no pleasure seekers in the fjord. In such a wilderness of primeval rocks and eternal ice was launched the iceberg that made history.

Since 2000 the tongue of Jakobshavn Glacier has retreated from the coast at an alarming rate, and the ice flow behind has sped up. Jakobshavn, indeed, is one of the great loci of global crisis. Nowadays 35 billion metric tons of iceberg calve from the glacier each year and float oceanward down the fjord. Only about one-eighth of an iceberg is visible above water: the submerged seven-eighths can be so deep that icebergs get wedged on the floor of the fjord and remain jammed there until broken by the weight of other icebergs smashing onto them from the glacier. As they are largely submerged, the drift of icebergs is governed by current and little affected by wind.

Some icebergs from Iceland are carried by the East Greenland Current around Cape Farewell, where they join thousands of other icebergs from the western glaciers and together sweep into Baffin Bay. There they are taken by the Labrador Current, which carries them southward toward the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Many icebergs run aground on the coast of Labrador or on the northern part of the Banks and there disintegrate. The first appear near the Grand Banks about the beginning of Marchcold monsters that are so beautiful to look at and so dangerous to touch, in the words of a Cunard captain on the North Atlantic run. By the end of June they have ceased. During a normal year some three hundred to three hundred and fifty icebergs drift south of Newfoundland, and about fifty are borne south of the Grand Banks. Short of bombardment there is no means of destroying an iceberg except by waiting for it to melt. The largest of them drift twenty-five hundred miles before they dwindle away in the sun around latitude 40 north. From the bridge of a liner on a clear day a large iceberg can be seen at sixteen to twenty miles distance. In bright sunshine it appears as a luminous white mass. In dense fog its somber bulk is undetectable at more than a hundred yards. On a fogless night without a moon an iceberg would be visible at a quarter of a mile, but in moonlight it might be seen at a distance of several miles.

Field icegreat sheets of ice piled on one another by wind and currentsis formed on salt water. It is practically impassable, and a ship caught by it will have difficulty getting free without damage. Field ice drifts out of the Arctic all year long, carried south by the Labrador Current and supplemented by coastal ice. Often it runs ashore in bays along its route. It is susceptible to wind, unlike icebergs, and by early February of each year covers much of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. There it drifts at the mercy of winds and currents until it melts. It is hard to detect at much distance, especially by night, but can be spotted by a flickering luminosity in the sky called ice blink.

The Arctic winter of 19111912 was exceptionally mild. This accelerated the calving of icebergs from glaciers jutting over Greenlands west coast. The icebergs were larger than usual, which meant that they took longer to melt as they drifted southward. In April 1912 there was therefore more ice than usual floating in the Atlantic, and it was farther south than usual, too. During the previous months of February and March, violent storms had pounded the Newfoundland side of the North Atlantic. The three-thousand-ton sealing ship Erna vanished with thirty-seven souls; a schooner, Maggie, struggled for two months to cross from Portugal to Newfoundland untilbattered, leaking, and with one crewman deadit was crushed in the ice pack. By early April the tempests had abated, but the North Atlantic was strewn with spars, planks, and lost cargo. Over a thousand icebergs had drifted to the eastern edge of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland where for years at a time it had been rare to see an iceberg. As the Labrador Current sent these icebergs southward, a sheet of pack ice a hundred miles square went with them. In mild weather, icebergs may split apart with sharp reports, creating large lumps of ice called growlers. But in April 1912 the biggest bergs did not split into growlers. Instead, these hard, implacable masses headed at the rate of twenty-five miles a day toward the shipping lanes of the North Atlantic.

O N L AND

One of the most difficultstrictly speaking, impossiblethings for historians to recapture is a sense of what people did not know at the time.

T IMOTHY G ARTON A SH, F ACTS A RE S UBVERSIVE

Boarding

A seaport without the seas terrors, an ocean approach within the threshold of land... Enemies or tourists, missionaries or immigrants, they all entered or left land here, and in some other age their phantoms are still processing along Southampton Water.

P HILIP H OARE, S PIKE I SLAND

I n 1901 H. G. Wells likened the urban poor to an iceberg with much of its rock-hard bulk lurking under the surface: the submerged portion of the social body, a leaderless, aimless multitude of people drifting down toward the abyss. This submerged mass of the poor had accumulated from across the world, their recruitment accelerating as spreading railway and steamship routes more easily carried migrants from remote fastnesses to great cities. If the iceberg was a metaphor, the great modern liner was a paradigm of Western societya monstrous floating Babylon, wrote one of the Titanic passengers during its maiden voyage. G. K. Chesterton made a similar analogy between modern liners and the society that built them. Our whole civilization is indeed very like the Titanic; alike in its power and its impotence, its security and its insecurity, he wrote after the ships loss. There was no sort of sane proportion between the extent of the provision for luxury and levity, and the extent of the provision for need and desperation. The scheme did far too much for prosperity and far too little for distressjust like the modern State.