Tired of a society with unilateral and hierarchical power, the mentality of the past thirty years has evolved into a growing interest in the principles of negotiation and cooperation. The law of the strongest is now over: to ensure efficient work and positive energy, we must work together, create together and co-write the rules and projects that mark our daily lives. This trend is evident in both the professional sector and in our private lives.

Indeed, we negotiate every day: where to spend the next Christmas holidays, what film to see at the cinema, to get a raise, for more flexible hours, to finalise a contract that is favourable to both parties, etc. Therefore, learning to express our views and defending them while respecting those of the other party is crucial to leaving a negotiation feeling satisfied and confident.

Negotiating means daring to say what you want and raising points of contention in order to improve our daily or professional lives. It also means setting goals and leeway for reaching them. Finally, it means attempting to measure risks and compare them with the benefits of making changes. In 50 minutes, this book will help you to discover the challenges of this approach and the strategies you should implement for successful future negotiations.

Smooth negotiating: the basics

Apprehending the negotiation

Constitutive elements

Negotiations consist of two elements that define and distinguish them from any other communicative actions:

- an opponent

- a common goal.

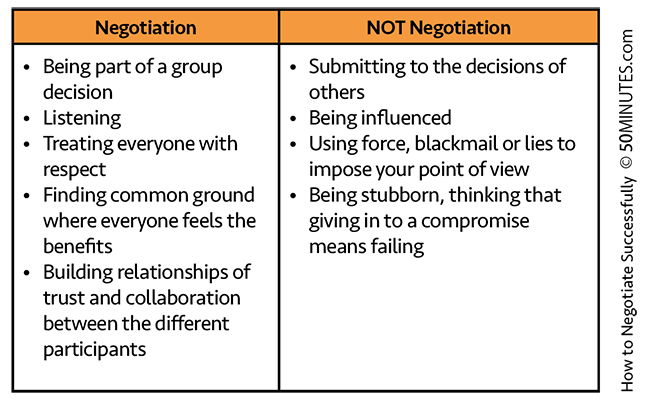

A negotiation pits two people or two parties with conflicting interests on one or more points against each other, face to face. Unlike a mere discussion or a pointless argument, the parties, driven by a common interest to come to an agreement, gather around a table to find common ground.

The argumentative exchange that takes place during a negotiation is therefore more complex and richer than that of a dispute in which the participants are content to shout their opinions and line up arguments without even listening to the other party. Through their desire to find an agreement, the negotiators need to be attentive to the needs and requests of the other party. Without neglecting their own interests, they should consider a solution that satisfies both parties. This is where the difficulty of the task lies.

When and why should I negotiate?

In order to improve our lives, we all have to negotiate both in our daily and our professional lives. Several objectives can lead to this approach:

- Resolving conflict (e.g. to develop a better division of household tasks between family members);

- Amending a contract (e.g. negotiating a salary increase or switching to part-time work);

- Improving an offer (e.g. as part of a property sale, the seller and the buyer must agree on a price);

- Finalising an agreement to optimise collaboration (e.g. a sports team and its main sponsor negotiate the money allocated, depending on the placement and the size of the logo on the players shirts).

Each party has something to gain from negotiation, so rather than sticking to your guns, you must engage in the process with a harmonious approach. However, before starting, you should check that the process is worth it. If, for example, you want to negotiate a schedule change when your employer has already modified it in your favour, you run the risk of your new request being interpreted as eternal dissatisfaction or as a sign of arrogance. This may make him overlook any of your future demands.

Overcoming prejudices

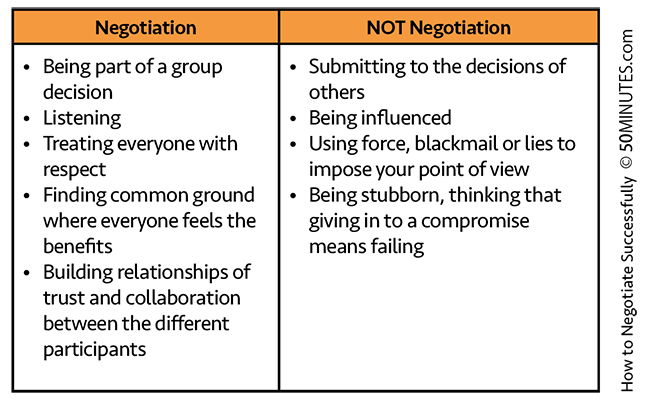

In our relationships, we act based on our previous experiences and preconceptions. Therefore, for the negotiation to go well, we must first condition ourselves to perceive the positive image of the process, far from stereotypes and prejudices that overpower our understanding.

Types of negotiations and relational games

Principled negotiation

There are different types of negotiations. Roger Fisher (1922-2012) and William Ury (born in 1953), founders of the Harvard National Project and negotiation specialists, have developed the method of principled negotiation, or win-win negotiation.

The method of principled negotiation developed at the Harvard Negotiation Project is to decide issues on their merits rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and won't do. It suggests that you look for mutual gains wherever possible, and that where your interests conflict, you should insist that the result be based on some fair standards independent of the will of either side. (Fisher and Ury, 1985: 6)

Principled negotiation consists of four principles:

- The dispute should be treated separately from the people involved (who have a role to play and must ensure they stick to a side in the debate);

- The discussion should focus on the interests of both parties and not their positions;

- It is better to imagine a large sample of potential solutions, rather than stay fixed on one;

- All participants must require the result to be based on objective and assessable criteria. These will be listed as The decision will be respected when.

Compliance with these four criteria ensures that we stay within the framework of a rational discussion, which covers only the subject of the debate and not peoples reputations, thus finding a practical and beneficial solution for both parties. This approach has the advantage of preventing the participants from taking a position they would struggle to leave, for fear of having to admit a semi-failure or feeling that they have lost face. The negotiation has a greater chance of success by starting from what is possible to submit for both parties and seeking common interests, rather than highlighting points of contention.

This technique is ideal for obtaining a satisfactory result for both parties because it does not mean fully satisfying the claims of both sides (this would be impossible), but rather reaching a fair agreement after a respectful discussion. The two specialists oppose the method of distributive (or competitive) bargaining, in which each party tries to maximise their gains without regard for the needs of the other. It is either win-win or lose-lose if negotiations fail.