Contents

FIRST VINTAGE CLASSICS EDITION, MARCH 2016

Translation, introduction, and notes copyright2002 by Julian Barnes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd., Toronto. This translation originally published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, London, in 2002, and subsequently published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 2003.

This work is based on the unpublished notes of Alphonse Daudet.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Classics and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows: Daudet, Alphonse, 18401897.

[Doulou. English.] In the land of pain / Alphonse Daudet; edited and translated by Julian Barnes. First American ed.

pages cm

I. Daudet, Alphonse, 18401897Diaries.

II. Daudet, Alphonse, 18401897Health.

III. Authors, French19th centuryBiography.

IV. SyphilisPatientsFranceBiography.

PQ2216.D6 E5 2002 843 .8 B 2002114929

Vintage Books Trade Paperback ISBN9781101970867

eBook ISBN9781101970874

Cover design by Megan Wilson

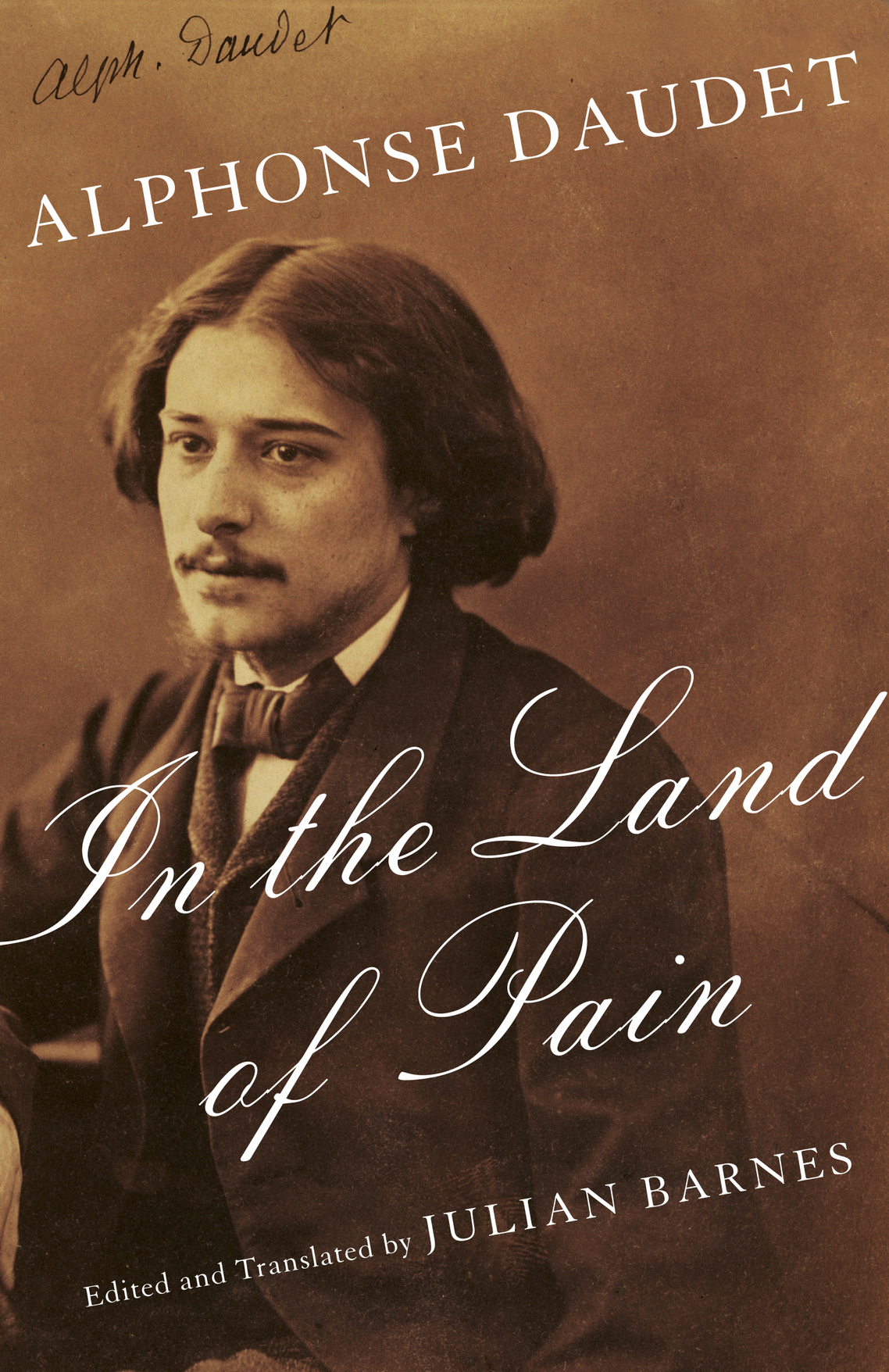

Cover photograph of Alphonse Daudet, around 1860, by Nadar The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

a

ALPHONSE DAUDET

In the Land of Pain

edited and translated by Julian Barnes

Alphonse Daudet was born in Nmes, France, in 1840. A novelist, playwright, and journalist, he found his greatest success through his novels and stories. He contracted syphilis at the age of seventeen and died at the age of fifty-seven.

Julian Barnes is the author of twenty-one books, for which he has received the Man Booker Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and Frances Prix Mdicis and Prix Femina, among many others. His work has been translated into more than thirty languages. He lives in London.

Daudet and his wife, Julia, at Champrosay, c. 1892.

Contents

Introduction

I n 1883 Turgenev had an operation in Paris for the removal of a neuroma in the lower abdomen. The doctors gave him ether rather than chloroform, and he was conscious throughout the intervention. Afterwards, he was visited by his friend Alphonse Daudet, with whom he had often dined in the company of Flaubert, Edmond de Goncourt, Zola and others. During the operation, Turgenev told him, I thought about our dinners and tried to find the right words to convey exactly the sense of the steel slicing through my skin and entering my bodyIt was like a knife cutting into a banana. Goncourt, recording this anecdote, commented, Our old friend Turgenev is a true man of letters.

How is it best to write about illness, and dying, and death? Despite Turgenevs impeccable example, pain is normally the enemy of the descriptive powers. When it became his turn to suffer, Daudet discovered that pain, like passion, drives out language. Words come only when everything is over, when things have calmed down. They refer only to memory, and are either powerless or untruthful. The prospect of dying may, or may not, concentrate the mind and encourage a final truthfulness; may or may not include the useful aide-mmoire of your life passing before your eyes; but it is unlikely to make you a better writer. Modest or jaunty, wise or vainglorious, literary or journalistic, you will write no better, no worse. And your literary temperament may, or may not, prove suited to this new thematic challenge. When Harold Brodkeys heroic and, it seemed, heroically self-deceiving account of his own dying was published in the New Yorker, I congratulated the magazines editor for leaving it all in, by which I meant the evidence of Brodkeys impressive egomania. You should have seen what we took out, she replied wryly.

Alphonse Daudet (184097) is a substantially forgotten writer nowadays. Novelist, playwright, journalist, he is viewed as a sunny humorist and clear stylist, creator in Lettres de mon moulin and Tartarin de Tarascon of an agreeable if partial Provence. He is offered to students of French as a nursery slope or climbing wall: practise on this. But in his day he was not only highly successful (and very rich); he also ate at the top literary table. Dickens called him my little brother in France; Henry James, who translated Daudets novel Port-Tarascon, called him a great little novelist; Goncourt mon petit Daudet. As may be deduced, he was short of stature. He was also kind, generous and sociable, a passionate observer and an unstoppable talker. These qualities transfer into his fiction. He was, in various descriptions (all of them from Henry James), the happiest novelist of his day, beyond comparison the most charming story-teller of the day, an observer not perhaps of the deepest things of life, but of the whole realm of the immediate, the expressive, the actual. As these assessments, laudatory yet limiting, imply, Daudet was the sort of writer hard-working, honourable, popular whose fame and relevance are largely used up in his own lifetime. The twenty-volume collected edition of 192932 seemed to have said (more than) it all. In Anglo-Saxon countries the surname Daudet nowadays refers as often to Alphonses elder son Lon, the highly gifted polemicist who followed an intransigent path to ultranationalism, royalism and anti-semitism; who was cofounder, with Charles Maurras, of LAction franaise.

If Daudet dined in the highest company, he was also a member of a less enviable nineteenth-century French club: that of literary syphilitics. Here again, he is somewhat overshadowed: the Big Three were Baudelaire, Flaubert and Maupassant. Daudet probably ranks fourth, equal with Jules de Goncourt, Edmonds younger brother. He could at least claim that the syphilis he acquired, shortly after his arrival in Paris at the age of seventeen, came from a classier, indeed more literary, source than theirs. He caught it from a lectrice de la cour, a woman employed to read aloud at the Imperial court. She was, he assured Goncourt, a lady from the top drawer.

After its initial declaration, and treatment with mercury, the disease lay dormant; Daudet worked, published, became famous, married (in 1867), had three children. He also continued an active, carefree, careless sex life. From the time he lost his virginity at the age of twelve, he had always been a real villain in matters of sex, he once confessed; he slept with many of his friends mistresses; about ten times a year he felt the need for the sort of