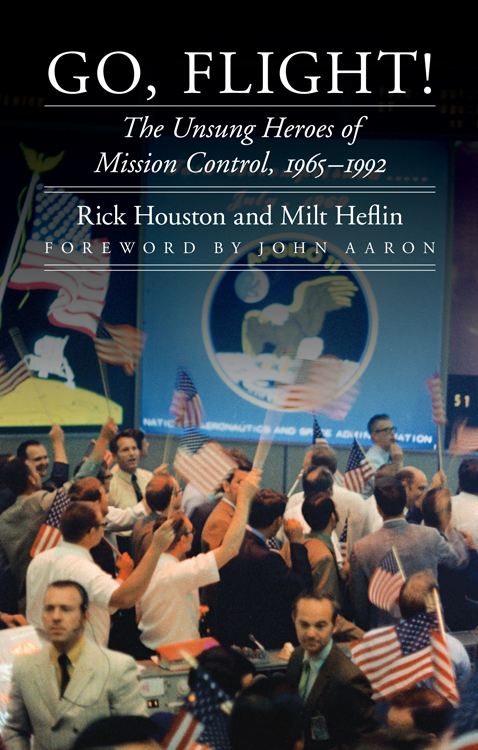

Those of us who worked in the MOCR [Mission Operations Control Room] were privileged to be in the right place at the right time in American history. We didnt know that sending men to the moon was impossible, so we somehow managed to do just that. We lived in a time when our vision was not limited by how far our eyes could see, but only by what our minds could dream. Authors Rick Houston and Milt Heflin are helping keep that dream alive in Go, Flight!

Milt Heflin did it all, from helping recover Apollo crews returning from the moon to overseeing the first make-or-break repair of the Hubble Space Telescope. Heflins insight and experience shine in his and coauthor Rick Houstons Go, Flight!, a firsthand glimpse into the fascinating world of mission control.

I experienced almost every emotion possible while working in mission control. Authors Rick Houston and Milt Heflin have taken me right back into the heat of battle with their outstanding book.

This book represents the most detailed account to date of how a group of ordinary men from rural America and smokestack towns became an extraordinary team that built the future. As well as tales of technical achievement, you will find the human stories about the band of brothers that formed mission control, and who became the best they could be.

Go, Flight!

The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control, 19651992

Rick Houston and Milt Heflin

Foreword by John Aaron

University of Nebraska Press Lincoln & London

2015 by Rick Houston and Milt Heflin

Foreword 2015 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image courtesy of NASA .

Author photo courtesy of the authors.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Houston, Rick, 1967

Go, flight!: the unsung heroes of Mission Control, 19651992 / Rick Houston and Milt Heflin; foreword by John Aaron.

pages cm.(Outward odyssey: a peoples history of spaceflight)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-6937-8 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8494-4 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8495-1 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8496-8 (pdf)

1. Project Apollo (U.S.)Biography. 2. Lyndon B. Johnson Space CenterOfficials and employeesTexasHouston. I. Heflin, Milt. II. Title.

TL 789.8. U 6 A 5 H 68 2015

629.4500973'09045dc23

2015008522

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Foundations of Mission Control

To instill within ourselves these qualities essential for professional excellence:

Discipline: Being able to follow as well as lead, knowing we must master ourselves before we can master our task.

Competence: There being no substitute for total preparation and complete dedication, for space will not tolerate the careless or indifferent.

Confidence: Believing in ourselves as well as others, knowing we must master fear and hesitation before we can succeed.

Responsibility: Realizing that it cannot be shifted to others, for it belongs to each of us; we must answer for what we do, or fail to do.

Toughness: Taking a stand when we must; to try again, and again, even if it means following a more difficult path.

Teamwork: Respecting and utilizing the ability of others, realizing that we work toward a common goal, for success depends on the efforts of all.

To always be aware that suddenly and unexpectedly we may find ourselves in a role where our performance has ultimate consequences.

To recognize that the greatest error is not to have tried and failed, but that in trying, we did not give it our best effort.

Contents

20 July 1969The Eagle had landed, and Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong and Lunar Module pilot Buzz Aldrin were now preparing for mans first walk on the moon. In contrast to the intense drama that played out earlier in the day, activities in mission control had settled down, and my fellow mission controllers were starting to relax, at least a little.

What a day!

What a day indeed!

Around 9 p.m., I realized I was drained. The days excitement and cliff-hanging moments had taken their toll on me. My relief, Charlie Dumis, had arrived earlier to take over the console duties, so I decided to unplug from my console and take a break before Neil and Buzz were scheduled to make their way out of the lander for the historic moonwalk. There was no way I was going to go home. Not yet. Not today.

I headed for the exit of the Mission Control Center building not realizing what I was about to experience. As I stepped out of the front door of the building, there it was, maybe thirty or forty degrees above the western horizon. A beautiful crescent moon appeared through the haze of that July Houston evening. That was the moment it hit me like a ton of bricks.

Neil and Buzz are on the moon. They are really there.

I was completely awestruck by the view. As a boy growing up in rural Texas and Oklahoma, I spent many evenings outdoors and had watched and wondered about our moon countless times over, but suddenly things changed. The impact was immediate, and in a way that I have never looked at the moon the same way since.

I reported for work that morning feeling a bit anxious about the days challenge, even though I felt prepared for the task at hand. During previous Gemini and Apollo missions and for countless numbers of mission simulations, my days had been spent preparing, monitoring, and managing spacecraft systems using my consoles racks of status lights, data displays, and voice communications circuits.

Although John Aaron very nearly left the agency early in his career, he went on to become one of the most capable flight controllers ever to sit a MOCR console. Courtesy NASA .

However, today was to be no simulation. This was the real deal. Two months earlier, Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan performed a powered descent to within nine miles of the lunar surface. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were going to try to go the rest of the way and settle the Eagle spacecraft down on the dusty plains of the Sea of Tranquility. And sure enough, following a nail-biting, drama-saturated, should-we-keep-going powered descent to the surface, it actually happened at just past 3:17 p.m. Houston time.

As EECOM , my attention was focused on the Command and Service Module ( CSM ) Columbia. I closely monitored the CSM to ensure all systems were ready for supporting the undocking and solo flight phase of the Eagle. After undocking, and with Command Module pilot Michael Collins still on board and orbiting sixty miles above the surface, the mother ship was performing well and all systems were in good shape. The focus in the room was now on the