Text copyright 2020 by Laura B. Edge.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Twenty-First Century Books

An imprint of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com .

Main body text set in Univers LT Std

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Designer: Viet Chu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Edge, Laura B., author.

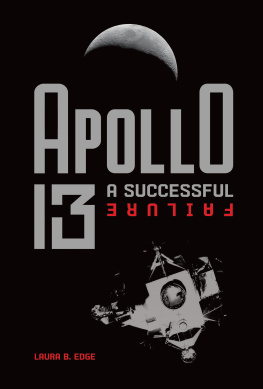

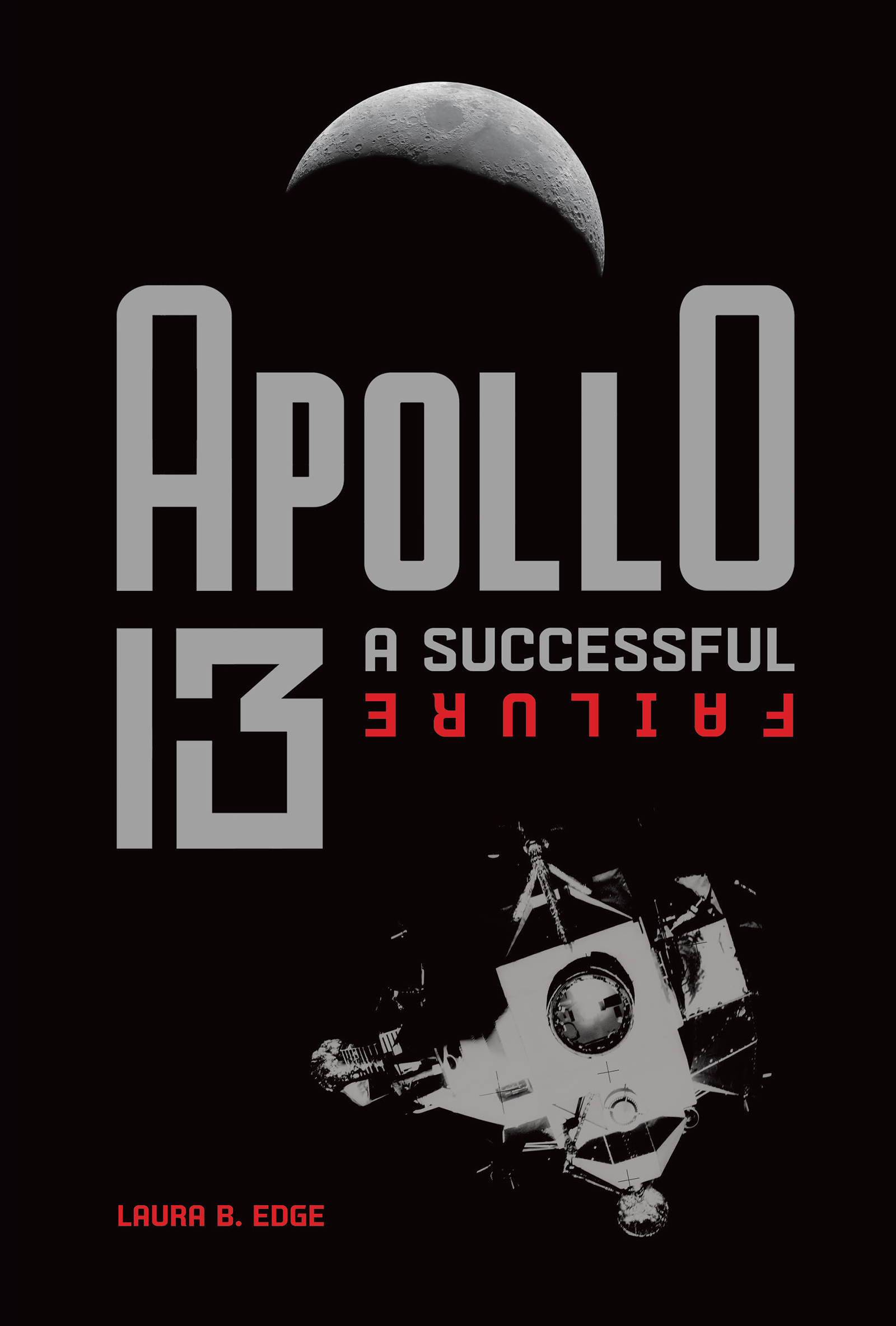

Title: Apollo 13 : a successful failure / by Laura B. Edge.

Description: Minneapolis : Twenty-First Century Books, [2020] | Audience: Ages: 12 to 18. | Audience: Grades: 9 to 12. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009210 (print) | LCCN 2019014184 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541581760 (eb pdf) | ISBN 9781541559004 (library bound : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Apollo 13 (Spacecraft)Juvenile literature. | Space vehicle accidentsUnited StatesHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | Project Apollo (U.S.)Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC TL789.8.U6 (ebook) | LCC TL789.8.U6 A53289 2020 (print) | DDC 629.45/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009210

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-46286-46270-9/12/2019

Contents

Explosion in Space

The Race for Space

A Dying Spacecraft

Lunar Lifeboat

The Moon out the Window

A Cold, Dark Journey

Splashdown

Whew, What a Mission!

The Last Men on the Moon

Apollos Legacy

Explosion in Space

Man must rise above the Earth, to the top of the clouds and beyond, for only thus will he fully understand the world in which he lives.

Socrates, 399 BCE

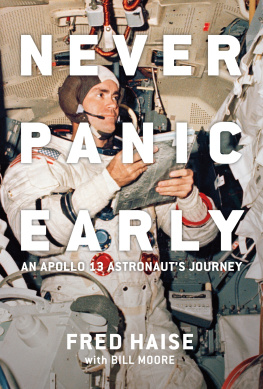

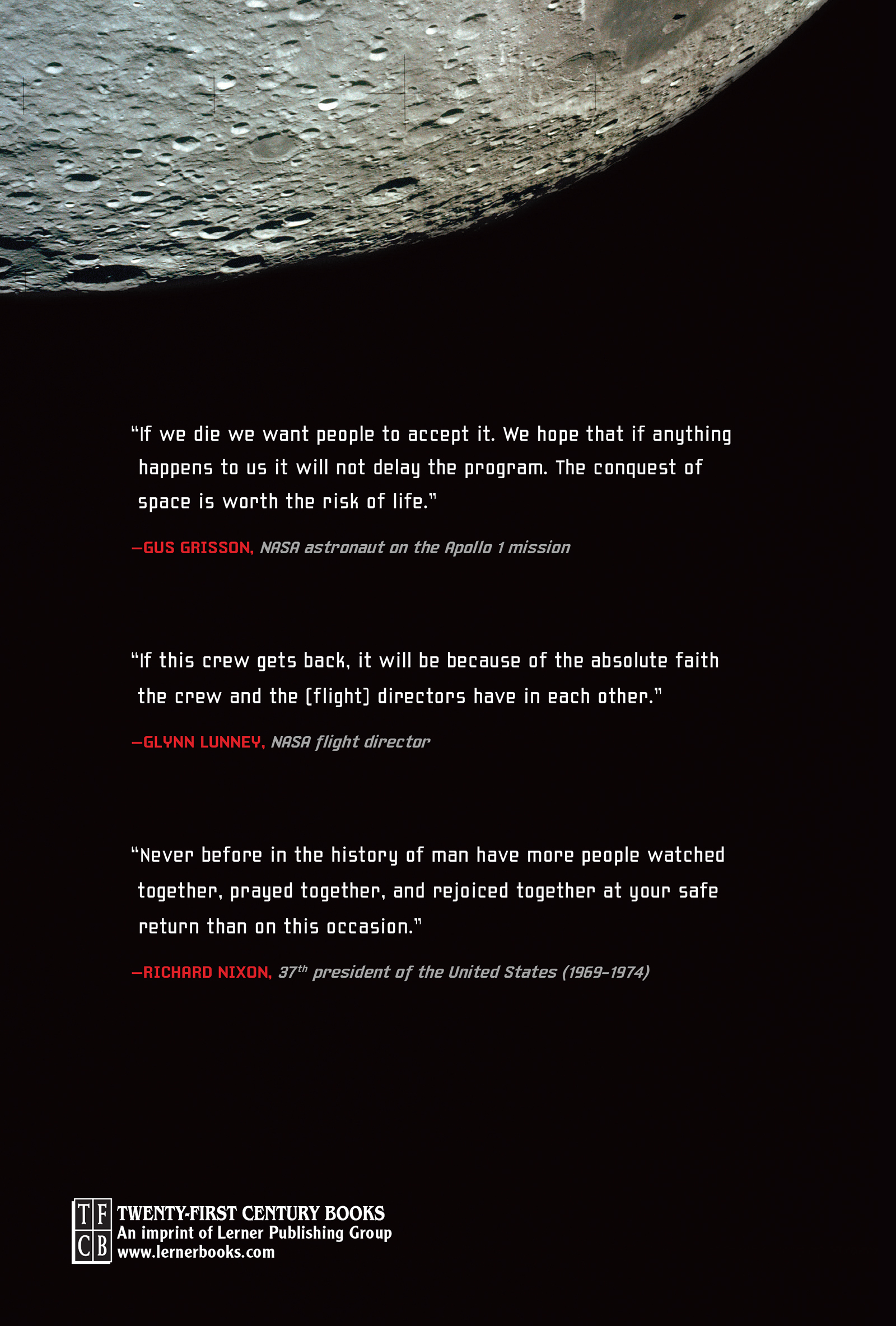

O n the evening of April 13, 1970, three astronauts floated around the Apollo 13 spacecraft in zero gravity. Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert were on their way to the moon.

The Crew

Flight commander Lovell knew from an early age that he would make rocket science his lifes work. As a boy, he read every book about rocketry he could find. In high school, with the help of his chemistry teacher and two friends, he built a rocket. The teens took it to an empty field, packed it with homemade gunpowder, and lit the fuse. The rocket blasted 80 feet (24 m) in the air, zigzagged a bit, wobbled, and exploded. Lovell was hooked.

After high school, Lovell studied engineering at the University of Wisconsin. Then he transferred to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis where he wrote his senior thesis on liquid-fuel rocketry. After graduation, he entered the naval flight-training program and became a test pilot for military jets. When the manned spaceflight program began looking for pilots to ride rockets into space, Lovell jumped at the chance to apply. The astronaut-training program accepted him.

By the time of the Apollo 13 launch, Lovell had flown three space missions and logged more hours in space than any other astronaut. He had circled the moon and seen its pale gray pits and craters outside the spacecraft window. On the Apollo 13 mission, he was getting ready to fulfill a lifelong dreamto walk on the surface of the moon.

Apollo 13 was the first spaceflight for the other members of the crew. Haise, a native of Biloxi, Mississippi, earned a degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Oklahoma. He served with the air force as a tactical fighter pilot and test pilot and flew for the marine corps, the navy, and the Oklahoma Air National Guard.

Exploration and the science of space travel fascinated Haise. He spent many hours learning how to identify different types of rocks. He practiced operating the geological equipment the crew would use to extract rock and soil samples on the moon. Haise looked forward to the discoveries their exploration of the moon would reveal.

Swigert was a last-minute replacement for astronaut Ken Mattingly. One week before the launch, a member of the backup crew came down with German measles. Before his symptoms appeared, he unknowingly exposed the primary crew to the disease. Blood tests revealed that Lovell and Haise were immune to German measles. Mattinglys blood test was inconclusive. Possibly, he could become sick during the spaceflight. Officials at the Kennedy Space Center felt it was too risky, so backup astronaut Swigert replaced Mattingly.

As a backup astronaut for the Apollo 13 mission, Swigert had trained alongside the primary crew for more than a year. Mere days before liftoff, he drilled rigorously with his new crew to prepare for the flight. The highly skilled pilot got his private pilot license at the age of sixteen. His degrees in mechanical and aerospace engineering provided Swigert with the knowledge and confidence to step into his new role on short notice. His service in the air force as a fighter pilot and test pilot proved he had the steely nerves required for a trip to outer space.

Teams of engineers, scientists, and mathematicians worked at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas. They monitored every second of the spaceflight, solving problems, adjusting equipment, and helping the astronauts keep the complicated spacecraft running smoothly.

James (Jim) A. Lovell Jr., Apollo 13 Commander

Fred W. Haise Jr., Apollo 13 Lunar Module Pilot

John Jack L. Swigert Jr., Apollo 13 Command Module Pilot

The Mission

The astronauts were well on their way to the moon. They planned to land Apollo 13 in a rugged, hilly area of the moon called Fra Mauro. Made up of ridges, hills, and valleys, the region interested scientists because of the variety in the landscape. Scientists hoped to gain insight into the moons geological history from the rock samples the astronauts planned to bring back to Earth.

An Unlucky Number

S ome people believe the number 13 is an unlucky number. In the ancient world, the number 12 was often considered the perfect number. The Sumerians developed a base-12 system that is still used for measuring time. A day is made up of two 12-hour periods. Most calendars have 12 months. According to this view, adding one to the perfect number is asking for trouble. Many high-rise buildings in the United States do not have a 13th floor, and many hotels, hospitals, and airports avoid using the number for rooms and gates.

So some people thought Apollo 13 was a terrible name for a dangerous flight to the moon. They wanted to call the mission Apollo 12B or Apollo 14. Anything but Apollo 13. And the digits of the launch date, 4/11/70, added up to 13. The launch was scheduled for 13:13 military time. But the astronauts didnt pay attention to the superstitious mumbo jumbo. They were highly trained professionals. They relied on science.