Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

With love to Alejandra, Elisa, and Paloma

for the bright sunlight

and the soft moonlight

August 1968

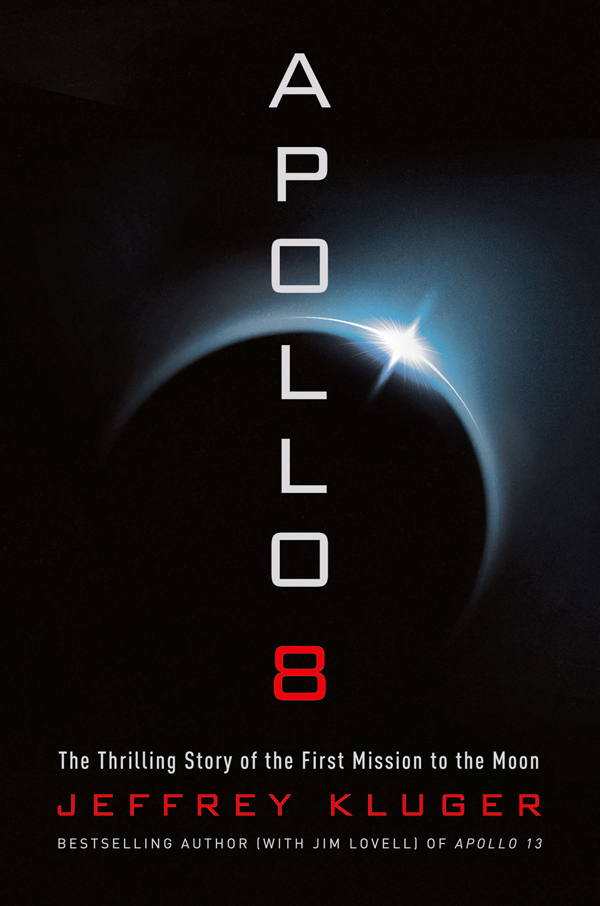

The last thing Frank Borman needed was a phone call when he was trying to fly his spacecraft. No astronaut ever wanted to hear a ringing phone when he was in the middle of a flight, but when the spacecraft was an Apollo, any interruption was pretty much unforgivable. The Apollo was a beautiful machineso much bigger, so much sleeker than the corrugated Mercury and Gemini pods that all of the other Americans who had ever been in space had flown. But the Mercurys and the Geminis had a perfect record: sixteen launches, sixteen splashdowns, and not a crewman lost. The Apollo, on the other hand, was already a killer: only eighteen months ago, three very good men had died in the first ship, before it even got off the launchpad.

So when Borman was trying to fly the cursed machine, he needed to pay complete attention. And now, at precisely the wrong moment, there was a call for him.

In fairness, Borman was not actually in midflight when the phone rang. No one had yet taken an Apollo into space; that would be folly until the ship was proven fit to fly, which it most assuredly had not been. For now, he was merely on the factory floor at the North American Aviation plant in Downey, California, where all of the new Apollos were being built. But Borman was sitting in the cockpit of an actual Apollo ship, one that was currently known as Spacecraft 104, though it would soon enough be called Apollo 9. And it was his ship, the one he would command if it ever got off the ground. If it did fly, Bormans place would be in the left-hand seatthe ranking seatand that suited him just fine. His crewmates, Jim Lovell and Bill Andersexceptional men, bothwould be in the center and right seats. Lovell and Anders were with him today, in fact, and the work they were doing was every bit as difficult as his own.

Apollo 9 was scheduled to launch in approximately nine months, which put Borman and his crew in the stretch run of their training. That schedule, however, depended on Apollos 7 and 8, the first two manned flights of the Apollo series; both had to get off the ground and bring their crews home whole and well. All three of the flights would be limited to Earth orbit, and to Bormans way of thinking, that was a shame. It was the boiling summer of 1968, and the world had spent much of the year bleeding from countless wounds: multiple wars, serial assassinations, riots and unrest from Washington to Prague to Paris to Southeast Asia. The Soviets and the Americans, again and always, were staring each other down in hot spots around the globe, while American boys died in Vietnam at a rate of more than a thousand each month.

A flight to the moonwhich President Kennedy had once promised would happen by 1970would have been a fine and bracing achievement right about now. But Kennedy was five years dead and three Apollo astronauts were eighteen months dead and the entire lunar project was flailing at best, failing at worst. Most people believed that if American astronauts reached the moon at all, they wouldnt get there for years.

Still, Borman had his mission, and he and his crew had their ship. And today they were inside it, running their flight drills and doing their best to get the feel of the machine. All of the Apollos looked the same and were laid out the same way, but spacecraft were like aircraft. Pilots could feel their differencesin the give of a seat or the grind of a dial or the stickiness of a switch that had a bit more resistance than it should. Each spacecraft was as particular to each astronaut who flew it as a favorite mitt is to a catcher, and you had best know your ship well before you took it into space.

Now, as Borman, Lovell, and Anders lay in their assigned seats in their small cockpit, working to achieve that fliers familiarity, a technician popped his head through the hatch.

Colonel, theres a phone call for you, he said to Borman.

Can you take a message? Borman asked, annoyed at the interruption.

No, sir. Its Mr. Slayton. He says he has to talk to you.

Borman groaned. Slayton was Deke Slayton, the head of the astronaut office and the man who made the crew selections and assigned all of the men to their flights. That power came with the understanding that he could always un -assign you to a flight if he chose. When Slayton rang, you took the call.

Borman crawled out of the spacecraft and trotted to the phone. What is it, Deke? he asked.

Ive got something important I need to talk to you about, Frank.

So talk. Im really busy here.

Not on the phone. I want you back in Houston now.

Deke, Borman protested, Im right in the middle of

I dont care what youre in the middle of. Be in Houston. Today.

Borman hung up, hurried back to the spacecraft, and told Lovell and Anders about the call, offering only a who knows shrug when they asked him what it meant. Then he hopped into his T-38 jet and flew alone back to Texas as ordered.

Just a few hours after he was rousted from his spacecraft, Borman was sitting in Slaytons office. Chris Kraft, Borman noticed with interest, was there as well. Kraft was NASAs director of flight operations; as such, he was Slaytons boss and Bormans boss and almost everyone elses boss, save the top administrators themselves. But today he remained silent and let the chief astronaut talk.

Frank, we want to change your flight, Slayton said simply.

All right, Deke Borman answered.

Before Borman could say anything else, Slayton held up his hand. Theres more, he said. We want to bump you and your crew from Apollo 9 up to Apollo 8. Youll take that spacecraft since its further alongand youll fly it to the moon.

Then, as if to make clear that the astounding statement Borman had just heard was really what Slayton meant to say, he put it another way: We are changing your flight from an Earth orbital mission to a lunar orbital. He added, The best launch window is December twenty-first. That gives you about sixteen weeks to get ready. Do you want the flight?

Borman said nothing at first, taking in the sheer brass of what Slayton was proposing.

Before Borman could fully gather his thoughts, Kraft spoke up: Its your call, Frank.

That, all three men knew, was entirely trueand entirely untrue, too. Borman was a soldier, a West Point graduate and an Air Force fighter pilot. He had never had an opportunity to fight in a hot war, but the space program was a race with the Soviet Union and a critical part of the Cold War. A battlefield assignmentno matter what kind of battlefieldwas not something he could possibly turn down.

The way Borman saw it, circumstances might warrant your saying no to a dangerous assignment, and your commanding officer might forgive you for saying no, but if you hadnt signed up to fight, then why did you become a soldier in the first place? And if you hadnt joined the space program to fly to the moon when your boss and your nation andsomewhere in that long chain of commandyour president were asking you to, well, maybe you should have chosen a different line of work. The Apollo spacecraft might not be up to the job, the flight planners who had the same sixteen weeks to get ready for a mission to the moon might not know exactly what they were doing, and in the end three more Apollo astronauts might wind up dead. But death was always a part of the piloting calculus, and this time would be no different.