Preface copyright 2000 by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger

Copyright 1994 by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 0-618-05665-3

ISBN 978-0-618-05665-1

e ISBN 978-0-547-52623-2

v1.1015

This book was previously published as Lost Moon.

Frontispiece: Official Apollo 13 emblem, courtesy of NASA

This true adventure is dedicated to those earthbound astronauts: my wife, Marilyn, and my children, Barbara, Jay, Susan, and Jeffrey, who shared with me the fears and anxieties of four days in April, 1970.

JIM LOVELL

With love to my familynuclear and extended, past and presentfor providing an always stable orbit.

JEFFREY KLUGER

Preface

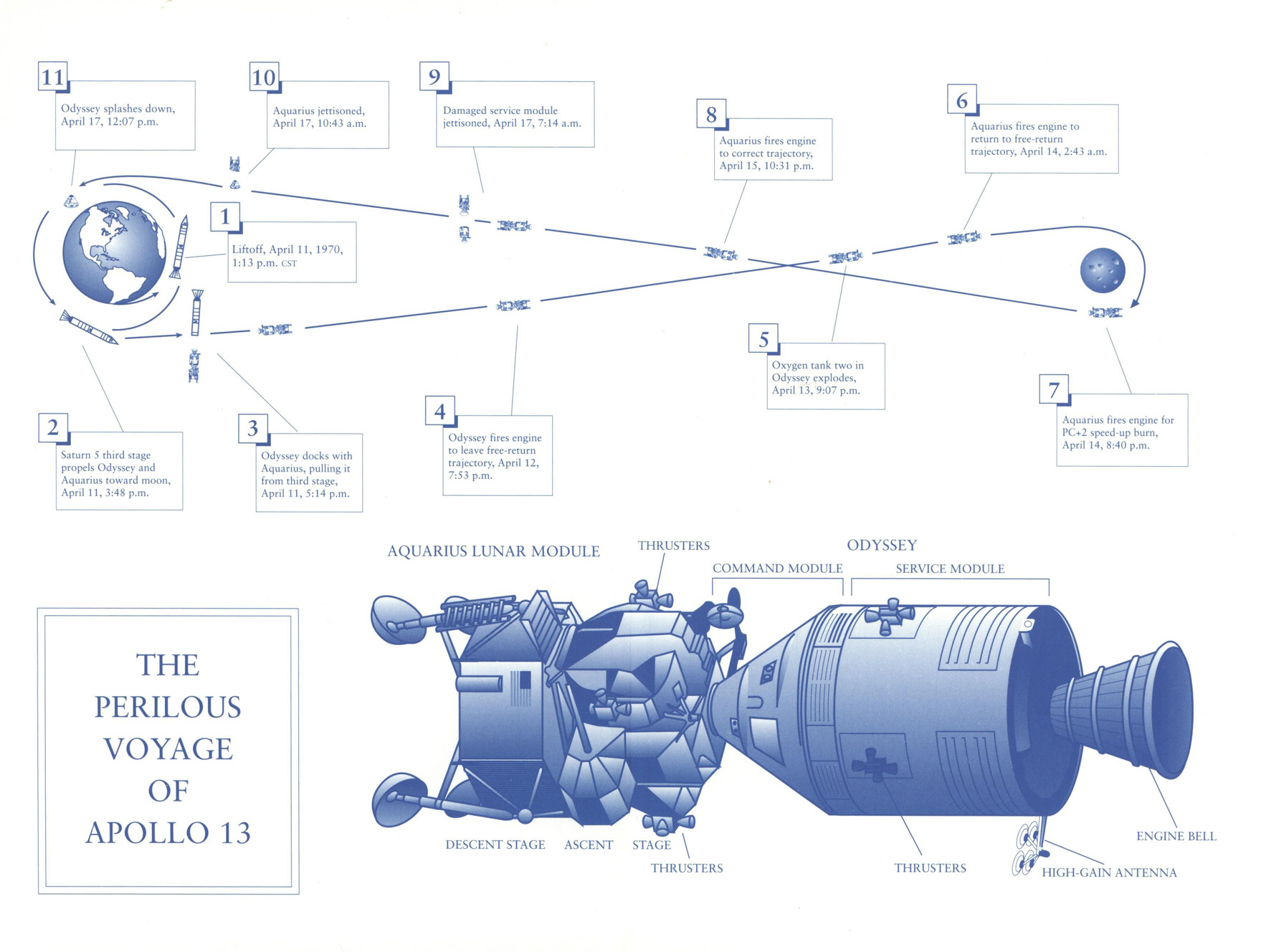

T HE MEN of Apollo 13 had a lot of plans for the afternoon of April 21, 1970. If the schedule ran the way it was supposed to runand there was no reason to assume it wouldntApril 21 was the day they would splash down in the Pacific Ocean and climb aboard the deck of the helicopter carrier Iwo Jima, having just completed humanitys third and most ambitious landing on the moon. Unlike Apollos 11 and 12, which had been sent to the glass-smooth plains of the Sea of Tranquillity and the Ocean of Storms, Apollo 13 would be heading for a high-wire touchdown in the moons Fra Mauro highlands. Negotiating a terrain that treacherous would require some sublimely good piloting, the kind that would prove not only the soundness of the translunar ships but the skill of the men who had been tapped to fly them. Pull off a mission like that, and the day you return to the familiar waters of the South Pacific ought to be a historic one indeed.

While the Apollo 13 crewcommander Jim Lovell and his rookie crewmates Jack Swigert and Fred Haiseindeed made history in the days leading up to April 21, it wasnt the kind they had expected. The mission they flew didnt involve pinpoint landings and memorable words and great, bounding bunny hops in the moons otherworldly gravity. Rather, it involved an exploding oxygen tank and a mortally wounded spacecraft and a crew marooned 200,000 miles from Earth with no right to expect they could patch their ship together again, much less turn it around and nurse it back home.

Nonetheless, the Apollo 13 astronauts did come home, hitting the ocean not on April 21 but on April 17a four-day difference that represented the time it would have taken them to descend to the lunar surface, visit awhile, and take off again. Lovell, Swigert, and Haise could not forget how unlikely their safe return home was. But they could also not forget that those four days were something that dark fortune and flawed hardware would now forever deny them.

For a crew that had been assigned a snakebit spaceship like the flawed Apollo 13, there was always the possibility of finagling another lunar trip. It was the machines that had failed on this mission, after all, not the men. But Lovell, Swigert, and Haise instinctively knew they were not returning to space any time soon. The Apollo 13 astronauts had barely escaped with their necks during their week in space, and everyone aboard the recovery carrier realized it. The fact that they did escape was the longest of piloting long shots, and a space agency surviving on public goodwill was not about to push things now, packing the same three men into the same sort of ship, flinging them back into the void, and inviting fate to have a go at them again.

If the astronauts could not rewrite their personal story, however, they could still tell the one they had. Apollos 11 and 12 might have landed on the moon a year earlier; Apollos 8 and 10 might have orbited it before them. But no other crewno Americans, no Soviets, not a soul who had ridden a rocket into space beforehad ever come so heartstoppingly close to cashing it in out there and yet somehow managed to make it home. Refract the failed Apollo 13 mission through the right prism, and it started to look an awful lot like a success.

When the Apollo 13 crewmen were plucked from the ocean and flown to the carrier on April 17, they didnt have much opportunity to talk. But as the afternoon wore on and the welcoming ceremonies wound down, and Lovell, Swigert, and Haise stood with a handful of carrier officers, saying their final thanks in the crisp blue jumpsuits theyd donned in the helicopter to replace the wilted white flight suits theyd been wearing for the last six days, Lovell had a moment to pull Swigert aside.

We ought to write it up, Jack, the commander said to the command module pilot. Swigert looked at him perplexed. The story; this story, Lovell said. We ought to write it.

The idea of telling the tale of Apollo 13 was always a natural oneor at least it seemed that way to the men who had been involved in the mission. The problem was, who in the world would read it? By 1970, the United States had been flying in space for nine years, and while Americans had developed a fondness for their spacecraft and their astronauts, they had come to expect the missions to turn out one way: successfully. Oh sure, there had been that nasty bit of business back in 1961 when Gus Grissoms Mercury 7 capsule sank in the Atlantic the moment after it splashed down. There had been that hair-raising time five years later when Neil Armstrong and Dave Scotts Gemini 8 suddenly began pinwheeling in Earth orbit, requiring the crew to slam on the brakes and return home just ten hours into a flight that was supposed to have lasted five days. But while Gus and Neil and Dave might have known the kind of deadly mess they were in, the publicto NASA s reliefnever fully grasped it, figuring that as long as the boys got into space and came down all right, any minor scrapes they had before their feet hit the carrier deck didnt amount to much.

It was only in 1967, when the hard-luck Grissom, along with crewmates Ed White and Roger Chaffee, were killed in a launch-pad fire aboard the Apollo 1 spacecraft, that the taxpayers picking up the check for the missions realized the mortal price tag traveling in space could carryand they didnt much like it. Americans might be willing to continue funding NASA s increasingly risky cosmic expeditions, but give them too many flag-covered coffins or too many crepe-draped widows, and they just might drop the hammer on the whole operation.

For that reason as much as any other, the moment Apollo 13 returned from space, NASA did everything it could to get the nations mind off the near-catastrophic mission. Lovell, Swigert, and Haise got their requisite parades; Congress held its requisite hearings into the accident, determining which pieces of hardware and which prelaunch errors had led to the explosion. But after that, the space agency moved on to other things, gearing up as quickly as it could for Apollo 14 and pointing proudly to all those other magnificent Apollos that had come before. Even the Apollo 13 spacecraft itself was soon forgotten. After the command module sizzled into the Pacific, it was hauled onto the carrier deck and then shipped to California for a post-flight physical at the plant where it had been manufactured. Engineers descended on the ship, stripping its innards, testing and retesting its on-board systems to determine how well they had survived their journey and what could be done to improve them for future missions. Afterward, the gutted spacecraft was shipped to Florida where it sat, largely overlooked, as part of an out-of-the-way Cape Canaveral display. After a few years of such internal exile, it was banished even further, expatriated to France where it would be kept in an aviation museum outside Paris.