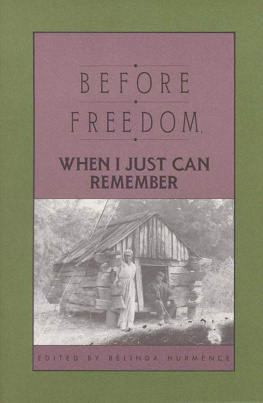

BEFORE FREEDOM, WHEN I JUST CAN REMEMBER

Other books by Belinda Hurmence

Tough Tiffany

A Girl Called Boy

Taney

My Folks Dont Want Me to Talk about Slavery

The Nightwalker

Copyright 1989 by Belinda Hurmence

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Fifteenth Printing 2009

Cover photograph

Brutus, an ex-slave at his home on Palawana Island.

From the Penn School Collection.

Courtesy of Penn Center, Inc.,

St. Helena Island, South Carolina.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Before freedom, when I just can remember : twenty-seven oral histories of former South Carolina slaves / edited by Belinda Hurmence.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

ISBN 0-89587-069-X: $8.95 (est.)

1. SlavesSouth CarolinaBiography. 2. Afro-AmericansSouth CarolinaBiography. 3. South CarolinaBiography. 4. SlaverySouth CarolinaHistorySources. 5. Oral history. I. Hurmence, Belinda.

E445.S7B44 1989

975.600496073022dcl9

89-243

[B]

CIP

for Joanne Bailey Wilson

Contents

A mericas infamous period of slavery casts a long shadow on our national past, a shadow in which those human beings who were most affected are still but dimly perceived. History may readily assess the economics and politics that condemned an entire race to bondage for nearly 250 years, but it continues to conceal from us the slave trapped in slavery. After all, history as we know it, is the written record of a people, and the black slaves of America were, by law, illiterate. The writings of Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and a few others are scarcely representative of the four million slaves who attained Freedom only after a bitter and bloody civil war.

How, then, 125 years after the fact, can Americans learn about the lives of those four million before and after Freedom?

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, various government agencies initiated work programs across the country to provide jobs for the unemployed. The Library of Congress supervised the program conceived for jobless writers. One of the projects it undertook culminated in Slave Narratives, a collection of black folk histories.

The Federal Writers Project sent field workers to interview blacks who had lived under slavery and recalled their experiences of it. Most of the ex-slaves were found in the South, although a sizeable number reported from states not generally regarded as southern. The project yielded oral histories on a scale unprecedented at the time.

In a time before the tape recorder, the field workers asked the former slaves a list of questions devised for the project and wrote out the answers. The interviews were compiled. Ten thousand pages of typed manuscript, representing some two thousand voices, were placed in storage in the Library of Congress.

Vivid voices they were, too, at last having their say about that murky time before Freedom.

Sylvia Cannon, former slave of Old Marster Bill Briggs, in Florence County: At night the overseer would walk out to see could he catch any of us walking without a note, and to this day, I dont want to go nowhere without a paper.

Fannie Griffin, ex-slave of Joe Beard in Columbia, South Carolina: I think about my old mammy heap of times now and how Is seen her whipped, with the blood dripping off of her.

The concept of bondage has always fascinated free Americans. With slavery more than a century behind us, and beyond the recollection of any living person, the fascination still persists. Perhaps the invisible, traumatic ties that bind us evoke a dread empathy with the physically enslaved. Scholars, researchers, and writers have always felt the tug of emotions adherent to the Slave Narratives.

They have also felt bewildered by the material. For one thing, there is so much of it. For another, it is so uneven, sometimes joyous, sometimes bitter in tone. Some of the ex-slaves were more articulate than others. The expertise of the field workers in committing personalities to paper varied greatly.

The collection remained virtually untouched for years. In time, the Library of Congress microfilmed the entire ten thousand pages to make it more accessible to scholars. In more time, facsimile pages came to be published in multi-volume editions.

Twelve years ago, in gathering background material for a novel I was then writing, I discovered the Slave Narratives. Although I found the testimonies uneven, and the very bulk of them daunting, I saw at once the treasure that lay in the oral histories. The Narratives resounded with an authenticity I had not encountered before in any prose dealing with slavery. I set aside my novel and read on. It took me two years to read through the collection, and I ended up with a file of notes thick enough to fill a dozen novels. I subsequently wrote two, based on my notes.

The emotional content of the Narratives convinced me that they should be accessible to casual readers as well as to scholars and historians. Thus, I came to edit a selection, first from the North Carolina Narratives, now, as a companion volume, from the South Carolina voices.

The bucolic image of slaves living in contentment on the southern plantation has for years been labeled stereotypical. In the South Carolina Narratives, we may find over and over what appears to be a reinforcement of the label. Nostalgia veils many memories for the former slaves.

Times was sure better long time ago than they be now, says Sylvia Cannon.

While Peter Clifton from Kershaw County and the plantation of Biggers Mobley reports, Yes, sir, us had a bold, driving, pushing marster, but not a hardhearted one.

Of course, more than nostalgia cloaks South Carolinas ex-slaves. Age, for one thing was a factor; all the speakers were old. Old and poor. They made it into the 1930s, but a lot of them suffered the declining health that stalks old age and poverty. They also suffered the hopelessness of the Great Depression then blanketing their world. Through the scrim of the seventy intervening years, it was easy for them to view their past lives in bondage as a time of plenty, a time when pleasures were simple and their youthful energies high, a time when plantation life meant shelter, food, medical care.

Why is there no pervasive cry of rage from the former bondsmen? Why instead these protestations of affection for a condition which shames the civilized world?

It is useful to remember that Freedom, following the Civil War, brought virtually no improvement in the lives of the liberated. The former slaves knew themselves to be free, but they also recognized their powerlessness. Reconstruction had shattered their embryonic political aspirations. They had felt saferthey had undoubtedly lived saferin the fiefdom of their former masters. Uneducated and ignorant of the world outside the plantation, oppressed by the law, intimidated by night riders and Klansmen, few could see Freedom as a condition to be cherished.

And little support came from their former defenders, the victors in the recent hostilities. The war-weary Yankees had lost interest in the high principle for which they had fought. Like their southern counterparts, they focused their efforts on rebuilding the strained economy, and left the new citizens to endure Freedom much as they had endured slavery.

Thus, field hands who had been exploited as slaves were abandoned to exploitation as sharecroppers. Merely to subsist, women who had been house slaves continued cooking and cleaning during the day and took in washing at night. A century would pass before the civil rights advances of the 1960s appreciably altered their lot.

Next page