Famous Works of ArtAnd How They Got That Way

Famous Works of ArtAnd How They Got That Way

John B. Nici

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by John B. Nici

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nici, John B.

Famous works of artand how they got that way / John Nici.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-4954-7 (hardback : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-4955-4 (ebook) 1. Masterpiece, ArtisticPublic opinion. 2. Art and society. I. Title.

N72.5.N53 2015

701'.03dc23

2015008192

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Carol Lewine and Bill Clark,

extraordinary scholars, masterful teachers

Foreword

What Price Fame?

I ts a masterpiece, A signature work, A classic! With ever greater frequency, masterpieces seem to come down to us fully validated as such, but who determines their rarified status? And, more important, how is it determined? What, in fact, does the designation of a work of art as a masterpiece actually mean? In contemporary usage, the definition trends toward a work of exceptional quality, or the most virtuosic example, a magnum opus, by a particular artista great artist, to be more exact. By implication, a masterpiecebe it visual, literary, dramatic, musicalawes its audience with its sheer genius, originality, and expressive power. In its modern conception, the designation in effect becomes largely aesthetic, presupposing a lofty cultural achievement. Yet it was hardly always thus.

The original meaning of masterpiece in a visual context was derived from medieval artistic practice and, more specifically, the obligatory requirements of guild membership. Having finished his or her training, a young or immigrant artist could only gain entry into the artists guild by finishing and submitting a test piece, a demonstration work that attested to its makers mastery of his or her chosen craft. In a rather unusual demand of rigor, one especially protectionist guild of painters and sculptors in late fifteenth-century Cracow is documented as having required as many as three exemplars, posing different representational challenges and thus testifying to the artists ability to conquer a wide range of technical problems. Upon the works acceptance, the applicants status as a journeyman or apprentice ended and that of full-fledged master began. The proof was thus in the skill: the most critical requirement separating a successful craft-masterpiece from a failing effort. On occasion, this very same precondition of supreme quality and skill was exploited by the guilds not only to elevate the socioeconomic status of a practitioner from artisan to artist or to protect the consumer from flawed, inferior products but to use it as an exclusionary tactic, foreclosing unwanted competition from foreigners within the local artistic community by means of arbitrary or prohibitively strict assessment. Local councils and individual patrons at times felt the stifling effects in their own right, protesting that guild protectionism ran the risk of compromising trade and even artistic innovation. By the mid-sixteenth century in Florence and the mid-seventeenth century in Paris, guild control was sharply on the wane; in its place arose the government-sanctioned academy. The requirement of a qualifying masterpiece or diploma work for entry still persisted into the age of academies, though in an increasingly more relaxed and pedagogical spirit.

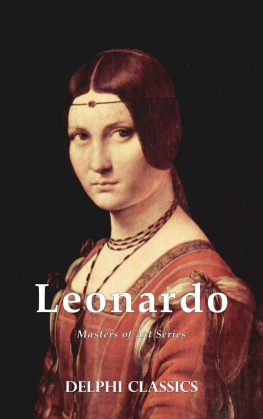

To return to the present day, what one might call the masterpiece effect is inextricably tied to currency, in both senses of the word: hard currency and the currency of fame. This, too, was not always thus. Do we know the identity of the makers of the Great Sphinx? Was the Mona Lisa ever delivered to its patron, Francesco del Giocondo and his wife Lisa Gherardiniin fact, was Lisas likeness even finished? (The answer on both counts is no.) And how many masters now universally lauded for the masterpieces contained within the present books covers were rejected during their own lifetimes? Many now-revered names headline this otherwise surprising list, wearing, in their afterlife, their former repudiation as a badge of honor. In the last two centuries alone, one need only to recall the names of William Blake, Vincent van Gogh, douard Manet, and Amedeo Modigliani in this regard.

Of the twenty highest known prices ever paid for paintings, all but two of them (both late canvases by Van Gogh) sold post-1990 at auction or, more commonly, in private sale, each and every one belongs to the usual late nineteenth- to twentieth-century artistic suspects. Headlining the list are four Van Goghs, four Picassos, two Warhols, two Klimts. All twenty works in question are now valued at an inflation-adjusted price of $100 million or above. Claiming the top perch is Paul Czannes Card Players of 18921893, purchased by the small, oil-rich state of Qatar in 2011 and valued at over a staggering $250 million. The painting is the most starkly spare of five known versions of the same subject, the other four housed in distinguished museum collections. More recently, in 2013, Jeff Koonss jumbo-sized, stainless steel Balloon Dog from the artists Celebration series, perhaps the best known of Koonss playful yet heavily marketed creations, sold at auction for over $58 million, the record for any living artist. The clothing line H&M, which sponsored Koonss recent show at the Whitney Museum, soon launched a handbag emblazoned with the Balloon Dog , priced at $49.50. Giant images of the glossy canine immediately graced the faade of the newly opened flagship H&M on Fifth Avenue and Forty-Eighth Street.

Johannes Vermeer was one old master who may have stood to use some Koonsian commercial savvy. Held in the highest regard in his lifetime, as he is today, the great Sphinx of Delft dwelt in relative obscurity until his rediscovery in the late nineteenth century. Nor was his end a happy one. A year and a half after Vermeers sudden death at the age of forty-three in the winter of 1675, Catharina Bolnes, his widow and mother of their eleven children (ten of them still minors at the time), petitioned for bankruptcy. She claimed that her husband was not only unable to sell any of his own paintings during the ruinous and protracted wara reference to the French invasion of the Dutch Republic in 1672but that the painter-dealer was also left sitting with the paintings of other masters for which he had failed to find buyers. Ultimately, Vermeer plunged into a state of such decay and decadence, according to Catharinas sad account, and had taken his money troubles so to heart, that he had fallen into a frenzy, [and] in a day and a half he had gone from being healthy to being dead.

Bankruptcy likewise haunted Rembrandts final years. Despite the Amsterdam masters financial success not only as an artist but also teacher and art dealer (like Vermeer to follow), his penchant for lavish living forced him to declare bankruptcy in 1656. Even Rembrandts earnings from a subsequent auctionhis remarkable collection of art and antiquities boasting objects ranging from ancient sculpture to Far Eastern art and arms and armorand the sale of his house proved insufficient to pay off his mounting debts. Despite his dire financial troubles, it was in his late period that Rembrandt produced some of his most profoundly moving works, including Bathsheba (Louvre, Paris, 1654); Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph (Staatliche Gemldegalerie, Kassel, 1656); a Lear-like self-portrait (Frick Collection, New York, 1658); and The Jewish Bride (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 16651669).

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.