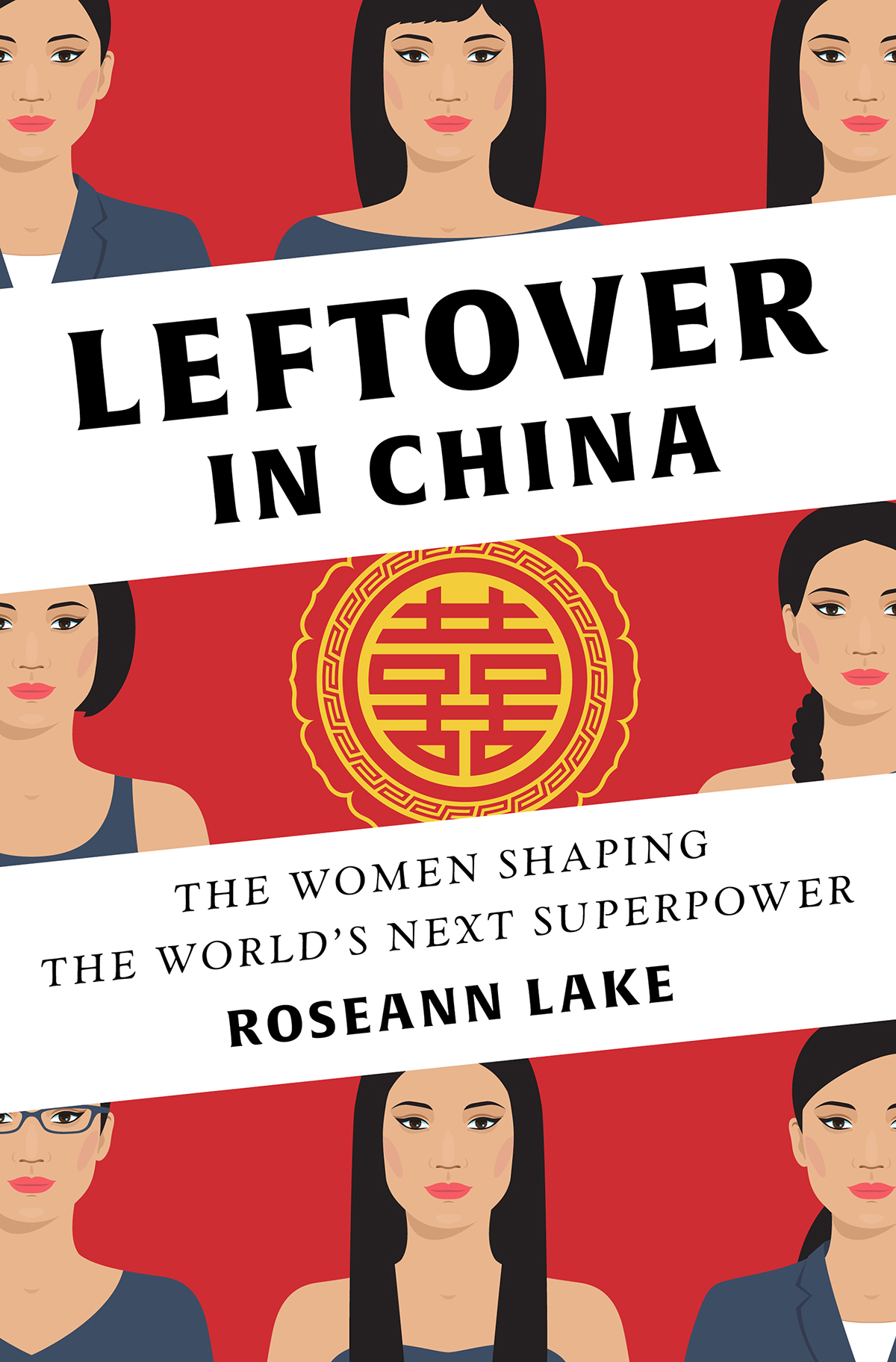

LEFTOVER IN CHINA

THE WOMEN SHAPING

THE WORLDS

NEXT SUPERPOWER

ROSEANN LAKE

The names and other identifying characteristics of many people who appear in this book have been changed. Certain characters are composites.

Copyright 2018 by Roseann Lake

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

JACKET DESIGN BY LINDA HUANG

JACKET ILLUSTRATION BY SUNNY SONG,

BASED ON AN ILLUSTRATION AUNAAUNA / SHUTTERSTOCK

ISBN 978-0-393-25463-1

ISBN 978-0-393-25464-8 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For my dear parents, Rosa and Ken

it doesnt look like Ill ever become an ophthalmologist,

but I hope this makes you proud.

For Steven Lakethe little brother like no other.

Os quiero!

CONTENTS

Just after Chinese New Year, I returned to the office of the Beijing television station where I had been working to find that all of my usually chipper young female colleagues were in decidedly different spirits. Even Shan Shan, the megawatt producer, had toned it down several joules and was uncharacteristically mum for a Monday morning. Did everyone have a nice holiday? I asked. I got a few unenthusiastic nods, a few forced smiles, and was handed a half-eaten bag of sesame balls that had been circulating around the newsroom. Puzzled, I went to see one of the network supervisors, a woman who was about ten years older than most of the women on staff. They are sad because they are not getting married, she said, as if this answer would make perfect sense to me. She then turned back to her computer, leaving me to wonder if Chinas answer to Mr. Darcy was coming to town, or if the Communist Party had just issued millions of free honeymoons to the Maldives.

Sitting down to lunch with Shan Shan later that day, I learned that Chinese New Year is famous for being the time of year when red envelopes are stuffed, dumplings are steamed, and singletons skewered. As the grand apotheosis of the Chinese lunar calendar and the longest yearly holiday that most Chinese workers are entitled to, its heralded by the mass migration of over 300 million people traveling home to feast and set off fireworks with their families. Yet as extended clans unite to eat, drink, play, and be merry, tidings of betrothals commonly take center stage. Gathered around tables festooned with fish heads, singles over age twenty-five are often assailed with well-meaning but often completely misguided offers of blind dates. Women, especially, are targeted in this marriage offensive, as it is considered imperative that they tie the knot by a certain age, lest they risk becoming sheng n or, literally translated, leftover women.

In addition to finding it highly objectionable that my still young and presumably fertile colleagues (the oldest just a few days over twenty-seven) were being referred to as the stuff of doggie bags and garbage disposals, I struggled to understand how this was all happening in modern China, the worlds largest economy,and professional opportunities that Chinese women had accumulated over the past thirty-odd years, though their label clearly indicated otherwise.

While at the studio, I found I was spending most of my time surrounded by a dynamite team of young female writers, editors, directors, and producers like Shan Shan. Quite naturally, over the course of delayed flights to Inner Mongolia, sleeper trains to Shanghai, and delirious overtime hours in our Beijing office, we bonded. Gradually, I became privy to their more personal conversationsthe juicy onesregarding their family histories, their aspirations, and increasingly, their love lives. The more I learned about the quirks of their dates and the complexities of their courtships, the more I was confused, surprised by what appeared to be a glaring inconsistency.

At the time2010the reports in Western media with regards to Chinese women had a very sanguine glow. As articles in Forbes , Newsweek , and Time were indicating, Chinese women were at the top of their game. They represented the highest percentage of self-made female billionaires in the world, and with 63 percent of GMAT takers in China being female, they were attaining MBAs with a ferocity that was making the boys blush. According to National Bureau of Statistics reports, 71 percent of Chinese women between the ages of eighteen and sixty-four were employed, and they accounted for 44 percent of the countrys workforce. The first one would soon be sent into space.

From what I could see, this was all true. Professionally, these women were so tenaciously pushing the limits of what was possible for their half of the sky, as far as I was concerned, they were all astronauts. Yet personally, and when it came to matters of the heart in particular, they appeared beholden to the playbook of another galaxya distant, anachronistic realm that seemed straight out of a Jane Austen novel. Much to my surprise, the recurring topic of our conversations quickly became marriage. They spoke of it as one might speak of an ingrown toenailwith urgency, a niggling element of pain, and the full knowledge that if it wasnt addressed in the imminent future, things would only get worse.

Sensing that something wasnt adding up, I began to do some digging beyond the scope of my newsroom comrades. Three years and several hundred interviews later, my curiosity has led me to understand the story of Chinas rise and development under a radically new lens. Its a story that begins with an impoverished Communist nation where marriage was universal, compulsory, and a womans only means to livelihood. Fast-forward thirty-plus years to an urbanized, globalized, economic superpower where marriage is swiftly becoming more discretionary and an institution that increasing numbers of educated women are committing to only after developing themselves and their careers a bit more fully, if theyre committing at all. Factor in the aftershocks of a nation still reeling from an onerous one-child policy that has saddled it with a walloping gender imbalance, and the plates in this wildly tectonic shift of social, economic, and demographic proportions begin to take shape.

Central to this shift is the idea that despite Chinas dazzling superlatives, there are strands of its culture that remain inextricably rooted in tradition, the most significant and inexorable of which is the societal pressure to wed. Although this pressure exists in varying degrees across many cultures and religions, it is particularly strong in China, where marriage retains the equivalent social force of a steamroller. This force makes it so that marrying off a child is the mission of just about every parent with offspring under the age of thirty. After thirty, the mission becomes a crusade.

In most cases, parents mean well. They genuinely believe that the best thing for their children is to assure that they are dutifully snuggled into wedlock as swiftly as possible, but there is a formidable cultural disconnect between progenitorswho were raised through poverty and revolutionand their progeny, who grew up through an economic boom and the birth of the individual in an otherwise fiercely collectivist society. This cultural disconnect is the essence of the infinitely textured and complex set of sparring values, obligations, traditions and tensions that define modern China, where like the perennial wind chime, changes in marriage policies and patterns have heralded the most significant shifts in Chinas sociopolitical climate. This has been true for the past five thousand years: a time during whichits critical to notemarriage has been the cornerstone and pinnacle of a womans life.

Next page