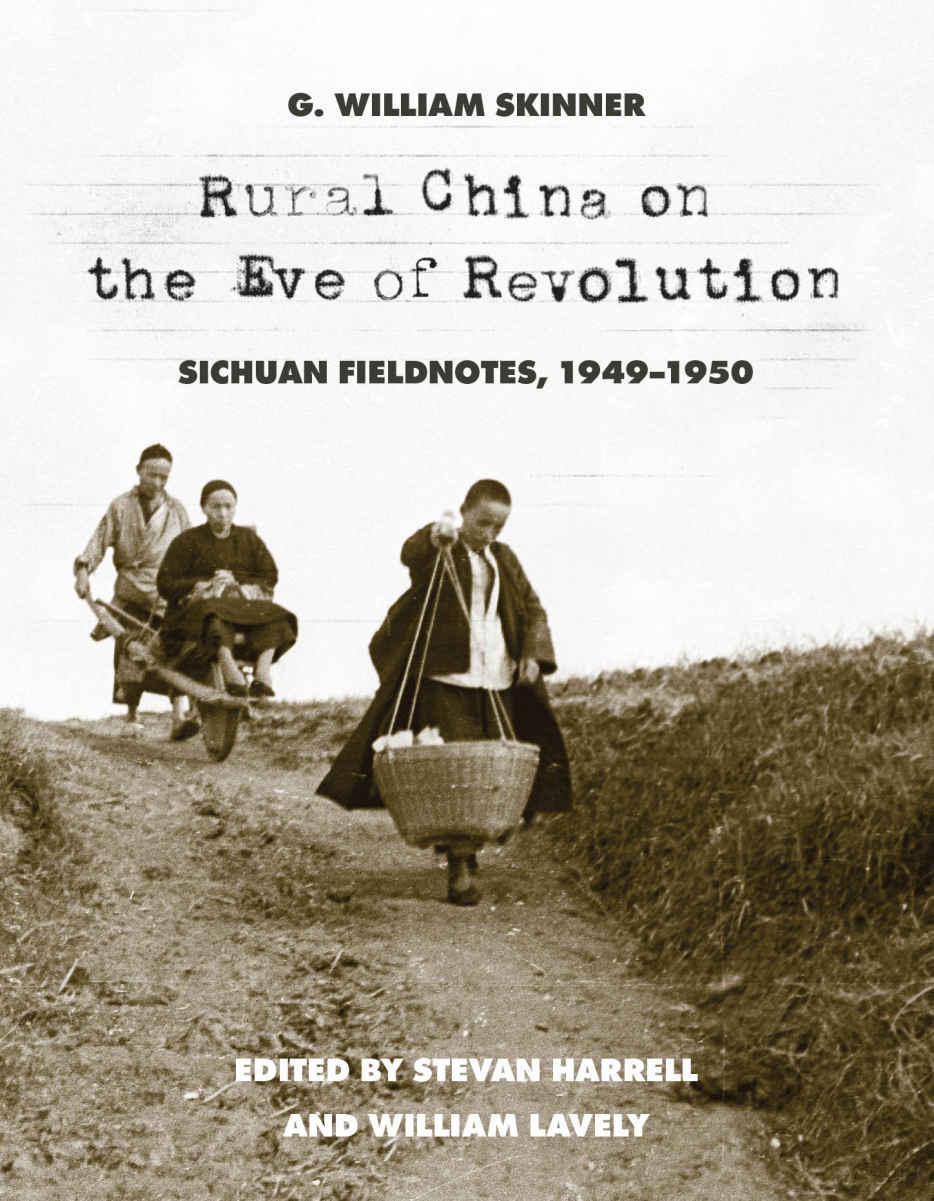

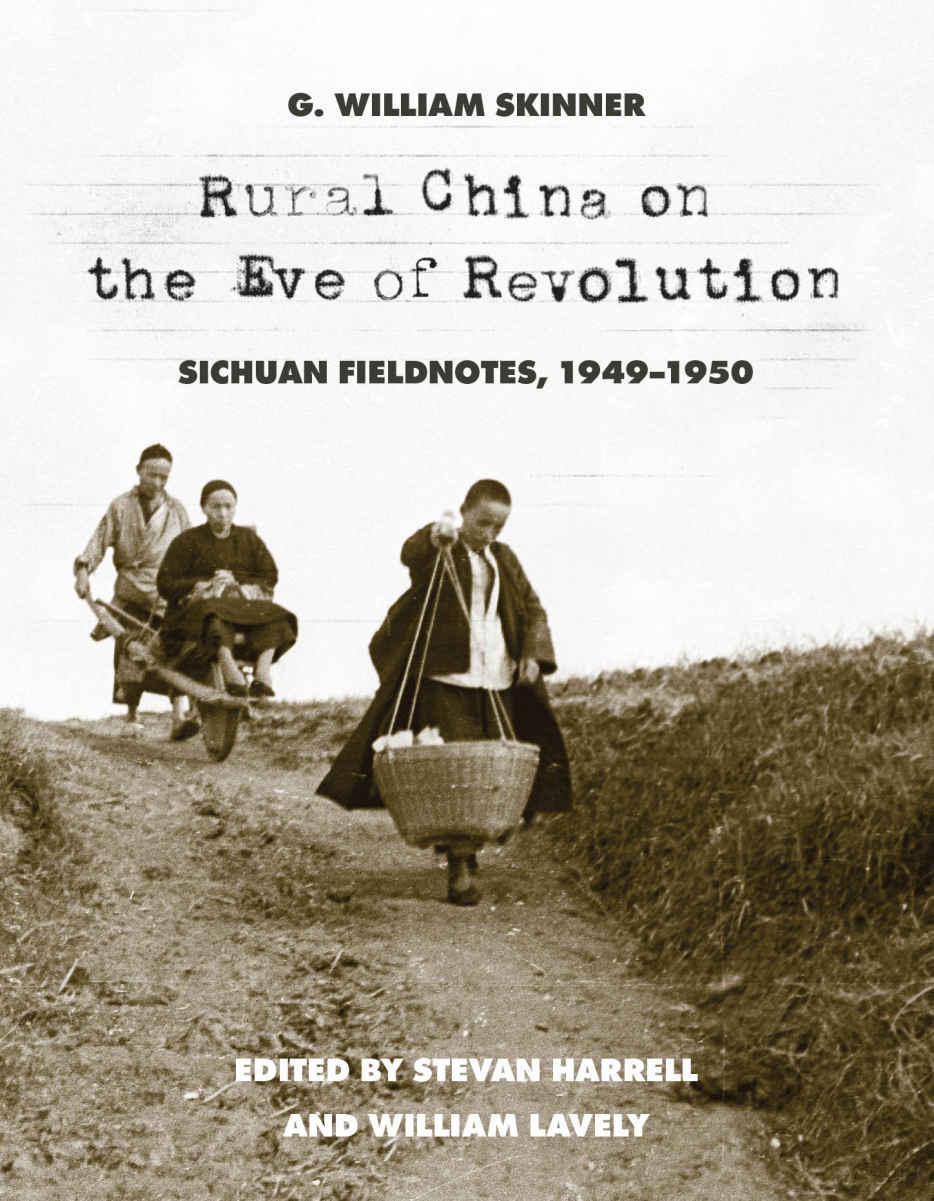

RURAL CHINA

ON THE EVE OF

REVOLUTION

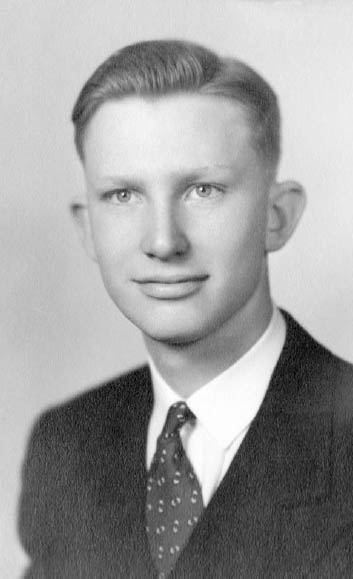

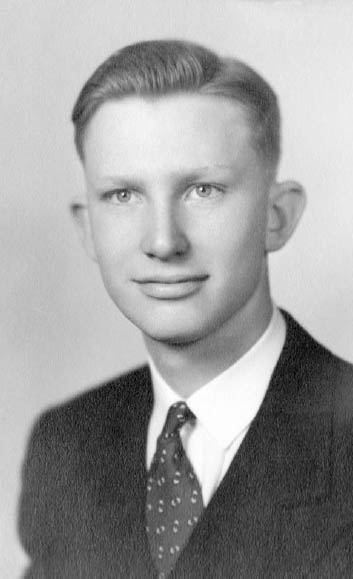

G. William Skinner, about 1943, six years before his Sichuan fieldwork. Photo courtesy of Susan Mann

Rural China on the

Eve of Revolution

SICHUAN FIELDNOTES, 19491950

G. WILLIAM SKINNER

Edited by Stevan Harrell and William Lavely

Rural China on the Eve of Revolution was made possible in part by grants from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and from the G. William Skinner Fund at the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology, University of Washington.

Copyright 2017 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in Minion, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES

www.lib.washington.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Skinner, G. William (George William), 1925-2008, author. | Harrell, Stevan editor. | Lavely, William, editor.

Title: Rural China on the eve of revolution : Sichuan fieldnotes, 1949<->1950 / G. William Skinner ; edited by Stevan Harrell and William Lavely.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016035717 | ISBN 9780295999418 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780295999425 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Social structureChinaSichuan Sheng. | Country lifeChinaSichuan Sheng. | Sichuan Sheng (China)Social conditions20th century. | Sichuan Sheng (China)Rural conditions. | Skinner, G. William (George William), 1925-2008Diaries.

Classification: LCC HN740.S54 S55 2017 | DDC 306.0951/38dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016035717

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.481984.

CONTENTS

by Stevan Harrell and William Lavely

PREFACE

Stevan Harrell and William Lavely

In summer 1949, George William (Bill) Skinner, a twenty-four-year-old PhD student in anthropology at Cornell University, had a problem. The Peoples Liberation Army was routing the Chinese National Army and was well on its way to taking over the entire mainland of China. Skinner, who was to become one of the most distinguished American anthropologists of China, needed a site where he could conduct the participant-observation fieldwork required for an anthropology doctorate. As the Chinese civil war drew to a close, his options were narrowing.

Skinners original proposal, submitted to the Social Science Research Council and the Viking Fund (later the Wenner-Gren Foundation), called for eighteen months of field research, living with a family in a village, preferably in north China, where he would carry out both general and focused research. His general ethnographic research would cover technology and economics, social organization, the systems of beliefs and sentiments, and the life cycle. His specialized studies would focus on individual personality, in order to contribute to the formulation of hypotheses about Chinese social personality formation and the congruence of personality and institutions, and to give insight into the psychological interrelation of various aspects of the total culture. He would also pay attention to the system of folk ethics, to comparative studies from other regions of China, and to culture change. Prominent in Skinners plans for specialized research were projective tests, in particular the Rorschach test and the Thematic Apperception Test, known as TAT. He also planned to record individual life histories and to utilize written materials that he could collect on-site.

Skinner had been an intelligence officer in the US Navy at the end of World War II, and his navy training in Chinese language made him an ideal candidate to carry out anthropological studies in China, a project that had the strong backing of his Cornell advisers, anthropologist Lauriston Sharp and historian Knight Biggerstaff. But the Chinese Communists were not at all inclined to allow an American anthropologist who was not himself a Communist to observe the unfolding events in Chinese villages.

Undaunted, Skinner traveled by ship to British-ruled Hong Kong, where he faced a dilemma, as he explains in the opening pages of his fieldnotes, written at West China Union University in Chengdu, Sichuan, on September 16, 1949. He could try to go to an area held by the Communists, such as the region around the capital (still called Beiping until October), or he could go somewhere that the Communists had not yet occupied, such as Sichuan or Yunnan, where the Nationalist government was still hanging on. He chose the latter course, which meant basing himself in Sichuan, and wound up living with a farm family near the market town of Gaodianzi, a few kilometers outside the city walls of Chengdu. The notes presented in this book are abridged from Skinners detailed record of his two and a half months of research there.

Because of Skinners later prominence and the key role that this short but eventful fieldwork in Sichuan played in forming his important analyses of Chinese society, his notes and photographs warrant a wider audience. The notes describe Skinners trip to Sichuan in summer 1949, his stay at West China Union University and his search for a field site, and his two and a half months of ethnographic research between mid-November and late January. In the notes we see the germination of ideas and themes that Skinner would pursue in a career spanning six decades.

Most important among these ideas are Skinners observations and nascent analyses of the rural periodic marketing system, which became the basis of his spatial model of Chinese rural social structure, his landmark work in the social-scientific study of China. Skinner saw the market community as the fundamental unit of rural Chinese society, connected to larger, more inclusive units through commercial and social transactions. He later elaborated this vision, proposing that China was composed presents the research area encompassed within the Upper Yangzi Macroregion.

Skinners other major scholarly interestsdemography and family structureare also amply represented here. In addition, there are meticulous and detailed descriptions of the material processes of rural life, from cooking and housecleaning to brick making and roof thatching, and of the everyday interactions among family members, adults and children. There is also a vivid record of the last annual festival of the Gaodianzi Dongyue Temple as well as a detailed account of the deities worshipped there. Finally, Skinners description of the foreign community in Chengdu before the Communist takeover, as well as the academic politics of a missionary university, are of considerable interest for the history of the Western presence in China. What is missing from the notes is any but the sparest reference to the Skinners planned psychological and personality research; falling so short of his original eighteen-month plan, he had not even begun testing when he was asked to leave the countryside at the end of January 1950.

Next page