JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU

HIS LIFE AND WORK

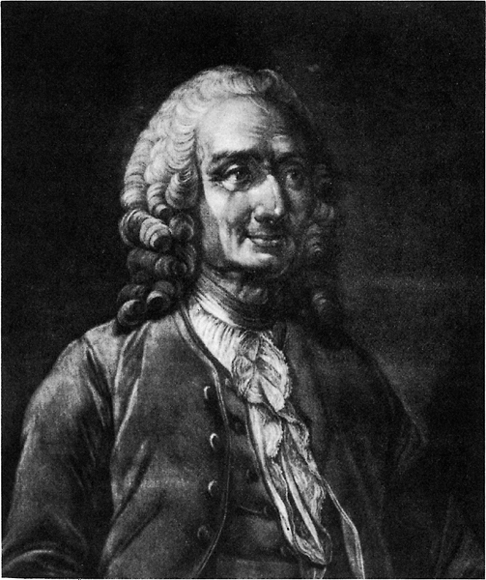

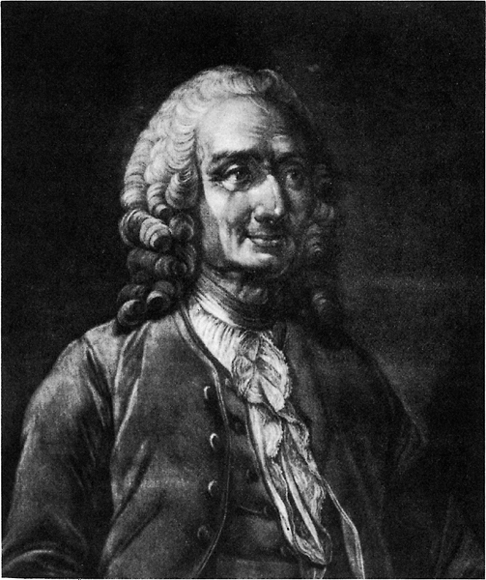

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU

from Dagotys Galerie franaise (1770)

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU

HIS LIFE AND WORK

CUTHBERT GIRDLESTONE

NEW INTRODUCTION

BY PHILIP GOSSETT

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Copyright

Copyright 1957 by C. M. Girdlestone

Copyright 1969, 2014 by Dover Publications, Inc.

Introduction copyright 2014 by Philip Gossett

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1969 and reprinted in 2014, is a revised and corrected edition of the work originally published by Cassell and Company, Ltd., in 1957. Philip Gossett has prepared a new Introduction specially for the 2014 edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Girdlestone, Cuthbert Morton, 18951975.

Jean-Philippe Rameau: his life and work / Cuthbert Girdlestone; new introduction by Philip Gossett.

pages cm

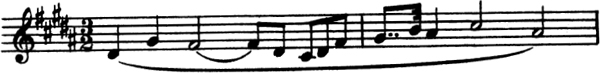

Summary: The definitive biography and critical study of the great 18th-century composer, this volume features full-chapter treatments of Rameaus operas and ballets as well as his chamber music, cantatas and motets, and minor works. Additional topics include acoustic and harmonic theories, links to Lully, and influence on Gluck. More than 300 musical examples, plus appendixes and indexesProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-78237-9

1. Rameau, Jean-Philippe, 16831764. 2. ComposersFranceBiography. I. Gossett, Philip, writer of added commentary. II. Title.

ML410.R2G5 2014

780.92dc23

[B]

2013021296

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49223001 2014

www.doverpublications.com

Introduction to the Dover Edition

I have always considered myself very fortunate in having known Cuthbert Girdlestone (18951975) early in my career as a musicologist, when he was already retired from his position as Professor of French literature at Armstrong College, which later became Kings College in Newcastle. Although a Professor of French literature, Girdlestone was known best for his work in music. In 1938 he published a book in French about Mozarts Piano Concertos, a book that went through several later editions and printings (including a translation into English in 1948), and was crucial in establishing the importance and beauty of all the Mozart Piano Concertos, not just the popular later Concertos, for todays audiences. But it was for his work on the French composer and theorist, Jean-Philippe Rameau, that Girdlestone is best remembered. His biographical study of Rameau, here reprinted by Dover Publications, definitively placed Rameaus music in our consciousness and helped create the basis for the revival of French opera so brilliantly launched by Bill Christie and his group, Les arts florissants.

But my gratitude to Cuthbert Girdlestone is more specific, for during 19651966 he would review, page by page, sentence by sentence, my English translation of Rameaus famous theoretical work, Trait de lharmonie (1722), the book that established the role of harmonic thinking in Western music. I had determined to work on this translation when I was still an undergraduate at Amherst College, writing a thesis on the development of French opera between the time of Lully and that of Rameau. In my nave and very partial knowledge of the repertory, I was convinced that among the significant differences between the earliest efforts to produce operas in French, and Rameaus remarkable first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie (1732), Rameaus harmonic thinking was of primary importance. Other scholars have since worked on this repertory with far greater acumen than I had as an undergraduate, among them Georgia Cowart, Charles Dill, Graziella Seminara, and Thomas Christensen. I have recently received a copy of a book by my former student, Cynthia Verba, entitled Dramatic Expression in Rameaus Tragdie en Musique: Between Tradition and Enlightenment, that picks up my earlier idea and treats it in a much more sophisticated way than I ever could have imagined doing.

I contacted the Music Library Associations committee, headed by the late Barry Brook, in the Spring of 1963. I knew that they were interested in producing translations of important theoretical works. I suggested to Professor Brook that I do a translation of this Rameau treatise. They must have laughed when they realized I had not yet begun graduate work in musicI was to attend Princeton University beginning in the Fall of 1963; I worked on the Rameau translation largely during the summer of 1964but they wanted a translation of the Treatise and here was someone apparently crazy enough to undertake the work. So they spoke with the publisher of the series they were contemplating, Dover Publications, Inc. Dover was also somewhat uncertain about giving such an important project to an unknown young man, but they had what turned out to be a brilliant idea: they would guarantee the quality of the translation by having it reviewed by Cuthbert Girdlestone himself And so, when I went to Paris during the 196566 academic year on a Fulbright fellowship, to work not on Rameau and French opera, but on the operas of Rossini, I set aside time each week to review the translation I had prepared while a graduate student with no less an eminence than Cuthbert Girdlestone.

In 1957 Girdlestone published his remarkable life of Jean-Philippe Rameau, in English, with its extensive analysis of Rameaus music and many musical examples, since at the time these operas were basically unknown. In his usual understated fashion, Girdlestone reviews the history of publications about Rameaus music, including the masterful work on the Rameau operas by Paul-Marie Masson, LOpra de Rameau (Paris, 1930)but he was too modest to state that Massons book was clearly written for specialists, whereas Girdlestone was writing for everyone who might wish to explore the music of the French Baroque. Not that he couldnt write a more specialized work when he so desired, as in his La tragdie en musique, considere comme genre littraire (Geneva, 1972), but he will surely be remembered most as a writer who could embrace complicated issues in language that could be understood by lovers of fine music everywhere.

As he says in the very first sentence of his preface to his 1957 Rameau study: My purpose in writing this book has been to draw the attention of music-lovers to the work and person of Rameau, so that they may acquaint themselves with that work, play it to themselves, if possible have it performed, enjoy it, and lead others to enjoy it. And how he succeeded, with the general public, specialists in performance, and among scholars! Today there are many who play Rameaus music, and we now know his operas from multiple performances by the finest musicians, especially under the direction of the American, Bill Christie. What a delight it was for me to witness a performance at the Paris Opra of Rameaus last work, Les Boradesa work that finds its way into Girdlestones book only tangentially and about which he says: It is unlikely that Les Borades will ever emerge from the caverns of its two manuscript sources. Despite this dire prediction, we now have had a chance to hear and see the last tragdie-lyrique that Rameau wrote before his death in 1764, a work which was never performed during the eighteenth century. We can now better grasp what Girdlestone means when he says that The music certainly deserves to be accessible and repays study. The entire book is an effort to recapture a style of music that seems to have all but disappeared, and has now miraculously come to life again. Indeed, as John Rockwell said in his review of the opera in the

Next page