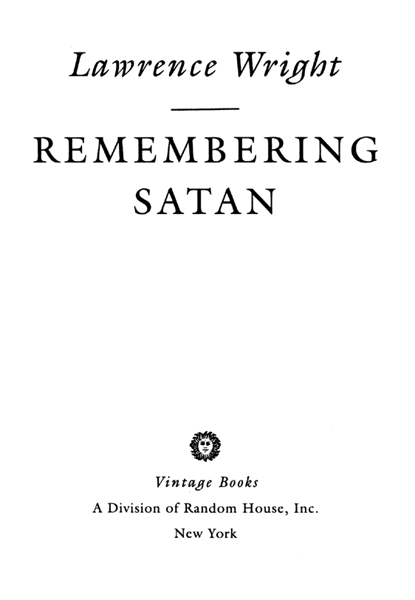

ACCLAIM FOR Lawrence Wrights

REMEMBERING SATAN

One of the real landmarks in journalism. The story itself is almost unutterably weird and would be fascinating no matter how well it was told but in the thoroughness of his reporting, and in his thoughtful treatment of the many issues the story touches, Wright has painted a perfect miniature of our time. Remembering Satan is an edge-of-your-seat tale.

Boston Globe

Skillfully and spellbindingly recounted.

San Francisco Chronicle

Brilliantly reported and compellingly written. Wright persuasively challenges the entire recovered memory movement.

Texas Monthly

Wright is particularly good at giving a fair and succinct account of this troubling controversy.

Chicago Tribune

[A] gripping and brilliantly constructed book.

The New York Review of Books

Wright makes brilliant use of this mind-boggling story to cast grave doubts on the whole notion of recovered-memory-syndrome. Admirably, Wright delivers a cool-headed, meticulous account of the case.

Entertainment Weekly

Compelling reading, expertly written. Wright tells an incredible true story.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

A cautionary tale about the dangers of so-called recovered memories. Remembering Satan is stunning.

The New York Times Book Review

Lawrence Wright

REMEMBERING

SATAN

Lawrence Wright is the author of City Children, Country Summer; In the New World; and Saints and Sinners. His articles have appeared in Texas Monthly, Rolling Stone, and The New York Times Magazine. He is a staff writer for The New Yorker and lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife and two children.

BOOKS BY LAWRENCE WRIGHT

Remembering Satan

Saints and Sinners

In the New World

City Children, Country Summer

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, MAY 1995

Copyright 1994 by Lawrence Wright

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage

Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and

simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited,

Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1994.

Portions of this work were originally published in The New Yorker.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the Knopf edition as

follows:

Wright, Lawrence.

Remembering Satan/by Lawrence Wright.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. False memory syndromeUnited StatesCase Studies. 2.

Ritual abuse victimsUnited StatesCase studies. 3. Adult child

sexual abuse victimsUnited StatesCase Studies. 4. Ingram,

Paul R.Family. I. Title.

RC569.5.R59W75 1994

364.I536dc20 93-23561

eISBN: 978-0-307-79067-5

Author photograph David MacKenzie

v3.1

For Tina Brown

lucky star

Acknowledgments

This book first appeared, in large part, in The New Yorker magazine, and I am grateful for the wise counsel of my editor, Kim Heron, and the tireless assistance of fact checker Peter Wells. I also would like to thank the investigators in OlympiaJoe Vukich, Brian Schoening, Neil McClanahan, and Loreli Thompsonwho were generous with their time and always helpful. Prosecutor Gary Tabor was always accommodating, and I thank him for his courtesy.

Elizabeth F. Loftus, at the University of Washington, has done much of the groundbreaking work on memory, and she afforded me a considerable amount of her valuable time and insight. Richard Ofshe, who has written about the Ingram case himself, was extremely helpful and insightful.

I owe a particular debt to Ethan Watters, a fine journalist who wrote about the Ingram case in Mother Jones. His research and perceptions about this case are reflected throughout this book. Thanks also to Cheryl Smith, who helped me decipher the workings of the polygraph, and Jan Mclnroy for combing through the manuscript with her careful eye.

Ann Close, my editor, and Wendy Weil, my agent, have been my invaluable companions and supporters for many happy years, and once again I acknowledge my gratitude for their advice and friendship.

Contents

O n the morning of Monday, November 28, 1988, the day that Paul R. Ingram was to be arrested, he dressed for his job, at the Thurston County Sheriffs Office, where he had worked for nearly seventeen years, went downstairs and ate breakfast, and then, to his surprise, suddenly vomited. He thought at first it must be the flu; then he realized that it was simply fear.

Ingram, who was forty-three, was already a familiar figure to most citizens of Olympia, Washington. Until that day, he had served as the chief civil deputy of the sheriffs department and the chairman of the local Republican party. He had been active in the deputy sheriffs association and in the Church of Living Water, a Protestant fundamentalist congregation. He was the father of five living children. (A retarded daughter had recently died in a state institution.) As a politician, he was seen as a bridge between moderate conservatives and the Christian Right. As a police officer, he was more highly regarded by the public than by other police officers. Tall and square-jawed, with oversized glasses and a brown mustache, Ingram was known in his department for being a hard-ass type who enjoyed traffic patrol. Although Ingram claimed that he gave as many as five warnings for every ticket he issued, it is also true that he routinely made more stops than most officers. He developed a reputation for handing out speeding tickets for driving just five miles over the limit, and yet his personnel file contained not a single complaint; instead it was filled with commendations from citizens who wished to thank him for the courtesy he had shown while issuing their citations.

At eight oclock that Monday morning, Ingram drove into the parking lot of the courthouse complex, which sits atop a hill beside Capitol Lake. Across the way, the white marble capitol looms, ghostlike, above the low-lying town, and beyond it one can see Budd Inlet, the farthest-reaching finger of Puget Sound. The briny air is full of the calls of seagulls, and the northern light is thin, even on a sunny day when the brooding Olympic Mountains are visible to the northwest and Mount Rainier shows off its snow-capped splendor fifty miles to the east. One can look at a map and imagine that the city is more vibrant than it actually is. The main highway on the western side of the state, Interstate 5, strings together Seattle and Tacoma, then reaches over to include Olympia before heading to Portland on its way to California. Olympia was once the largest port in the state, but with the decline of the timber industry the South Sound is virtually empty of maritime commerce. Neither the ferries nor the hydrofoils which course through the North Sound make a stop in Olympia. The city achieved a measure of regional fame through two local products that bear its name: the pale beer that is manufactured at the Olympia Brewery Company above the falls at the mouth of the Deschutes River, and the sweet, thumbnail-size oysters that grow in the bay. The brewery has long since sold out to Milwaukee interests; and as for the oysters, pollution and overharvesting have reduced them to an occasional, expensive delicacy.

Olympia became the capital of Washington Territory in 1853, when it was a bustling frontier outpost; now it is made up largely of bureaucrats, and the city bustles only when the legislature is in session. St. Peters Hospital and a cardboard-box plant operated by Georgia Pacific are the other leading employers. Olympia is bordered by the townships of Tumwater and Lacey, making up what is known as the Tri-Cities, with a population of 68,000Olympia proper accounting for just over half of that number. There are no skyscrapers, and parking is rarely a problem. Most people who live here like the slow pace, the modest scale, and the cozy society of small-town life. For many of them, the failure of the city to realize its early promise of becoming an industrial port like Tacoma or a sophisticated, international urban center like Seattle is a blessing that has allowed Olympia to stay charming and humane, if somewhat dull and self-satisfied.

Next page