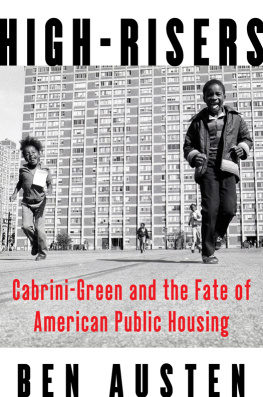

Ben Austen - High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing

Here you can read online Ben Austen - High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, publisher: Harper, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ben Austen: author's other books

Who wrote High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my family and my city

Moving through the rubble and babble down the locked-up, abandoned, ravished,sin-sacked and mildewed city; turning the cane about as if it were a symbolic key to the city givena visitor; a holy witness from another country come to save even you, and especially you. Nathanielbrooded now as they passed the government projectsadjacent to Rachels houseand the fad-riddennegro youths, harmonizing in a doorway, who apparently didnt know that their home was far overJordan.

LEON FORREST, The Bloodworth Orphans

Its not just buildings.

Its not a place,

Its a feeling.

Since we all confess,

To be raised in Cabrini was a blessing....

Cabrini is down but not out.

Have no doubt, Cabrini is Gods goods stretched out.

MICHAEL McCLARIN, Cabrini-Green resident

Put the city up; tear the city down;

put it up again; let us find a city.

CARL SANDBURG, The Windy City

T UCKED INTO THE elbow where the river tacks north, just beyond the Loop and a mile from Lake Michigan, it is as historic a neighborhood as there is in Chicago. In 2016, it was named one of the citys best places to live. A couple of generations earlier, and more than a century after the banks of the Near North Side were settled, surveyors from the Chicago Housing Authority walked its narrow streets, confirming with every step their belief that it was a slum beyond salvation. The field team from the CHA dodged trucks and trash heaps, careful lest they plunge into the open trenches dug for coal in front of the dwellings. The year was 1950, the quickening after the war, in the nations second city, yet everything looked to be of the benighted past. Almost all the buildings dated to the previous century. Many of them were cheap frame constructions slapped up after the Great Fire of 1871, temporary emergency shelters turned permanent. In their notebooks, the surveyors tallied the areas deprivations: nearly half of the 2,325 homes were without a bath or shower, many had no private toilet, and all but a few relied on coal stoves for heat. Over the previous decade, the population in the twenty-five square blocks had swelled to 3,600 families, increasing by 50 percent, yet only a single new residential building had been added. Flimsy partitions carved up the apartments into multiple units. Excuse the appearance of this place, a housewife apologized as she welcomed the researchers into her subdivided home. But we hardly have room to put ourselves someplace and there just aint room for anything else. Despite the conditions, rents had jumped by 70 percent. Landlords overcharged for their firetraps.

The following year, the CHA issued its report, Cabrini Extension Area: Portrait of a Chicago Slum, which depicted in lurid detail the neighborhood the agency hoped to replace. Houses, black with age and weathered with soot, lean precariously, and their uneven roof lines form crazy-quilt patterns against the sky. Chimneys tilt, eaves sag, rags stick out from broken windows, and doors without knobs stand open. There are few backyards. There cant be, when most of the lots contain two houses. Even the cover page sought to convey the ghetto in high squalor: a trompe loeil effect made the paper look burned and crumpled, as if found in one of the grubby alleys; the title was lettered in thick-markered graffiti script, with a drawing of a cockroach scuttling past the second i in Cabrini.

The employees of the Chicago Housing Authority in 1950 werent paper-pushing functionaries; they were self-proclaimed liberal do-gooders, many of them coming to the agency from social work. Their portrait of the Near North Side was meant to offend: they believed the slums of Chicago were killing people. House fires, infant mortality, pneumonia, tuberculosis, all occurred there at many times the rate found in the rest of the city. Poor housing conditions, the CHA noted, were contributing as well to high incidences of divorce, juvenile delinquency, and crime. The staff saw its work as a rescue mission: they needed to rid the city of blight. Houses work magic, their boss at the agency, Elizabeth Wood, would say. Give these people decent housing and the better forces inside them have a chance to work. Ninety-nine percent will respond.

Wood was an unlikely government official in the Chicago of the Democratic machine. Shed previously taught poetry at Vassar College and published a novel about an unhappily married woman who imparts her frustrations onto her children (A psychological study of merciless persecution, a reviewer wrote). She moved to Chicago to work for a welfare agency but found the job ineffectual; she wanted to do more than scribble notes as desperate clients detailed their wants. When the CHA was formed in 1937, she took over as its executive director. Private enterprise had failed to provide the agencys minimal requirement of a decent, safe and sanitary home for all. The Near North Side district was just one of the woeful examples that the CHA brandished as proof. Wood feared not that the citys new public housing projects might be too large, coming to define an area as low-rent, but that they wouldnt be large enough to counteract the ravages of poverty and disrepair around them. If it is not bold, she said, the result will be a series of small projects, islands in a wilderness of slums beaten down by smoke, noise and fumes.

One of the islands Wood and her team hoped to expand was next to the Near North Side slum. In 1942, the CHA opened the Frances Cabrini Homes, 586 dwellings in barracks-style two- and three-story buildings. Federal rules established that public housing be built to minimum standards, using materials and designs unmistakably inferior to those found in market-rate housing. The Cabrini rowhouses were simple and unadorned, arranged in parallel columns like lines of parked tractor trailers. But in the neglected river district, they stood out as an oasis of order and modernity. Like a challenge to the existing decay, the CHA declared. Each of the Cabrini Homes featured a gas stove, an electric refrigerator, a private bath, and its own heat controls. The buildings were made of fireproof brick. And the development was laid out so that parents could watch from their apartments as children played in communal courtyards. When you come upon one of Chicagos public housing developments, it is like stepping into a different world, the CHA rhapsodized in an early brochure. Everywhere you see greengreen of lawns, green of shrubbery, green of trees. Pleasant, vine-covered buildings stand in harmonious groups, with plenty of space left for sun and air and childrens play. Everywhere you see gardens, and overhead stretches a sky that somehow looks bluer and sunnier than it did in the slums.

The Near North Side was largely Italian for much of the first half of the twentieth century. But a small black settlement formed there as well. The federal government restricted overseas immigration after the First World War, and so the factories along the river had vacancies they needed to fill. Most people also made great efforts to live far from the areas polluted worksites and ramshackle homes. Thus, African Americans were able to move in.

That was an anomaly in segregated Chicago. As African Americans turned their backs on the South, their population in Chicago more than doubled between 1910 and 1920, from 44,000 to 109,000, and then more than doubled again over the next decade and again over the next twenty years, reaching half a million by 1950. Up until the 1940s, almost all of these newcomers moved to the South Side, in what was called the Black Belt, a broadening strip of land that extended south from the downtown business district.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing»

Look at similar books to High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.