HIGH RISE STORIES

Additional interviewers

MICHAEL BURNS, SHAVAHN DORRIS-JEFFERSON, JOYCE LEE, JILL PETTY, ERIC TANYAVUTTI, CRYSTAL THOMAS, AVA ZELIGSON

Transcribers

LYANNE ALFARO, GIOVAN ALONZI, CHARLOTTE CROWE, NICK DEBOER, IAN DELANEY, YANNIC DOSENBACH, SAUNDRA DOUGHERTY, HANNAH DOYLE, AZRA HALILOVIC, NATHANIEL LASH, MEGAN ROBERTS, ANN SZEKELY, TED TRAUTMAN, AND PAUL GARTON, INC.

Copy editor

ANNE MCPEAK

Fact checker

PETER STEPEK

Proofreaders

TREVOR SCOTT BARTON, MARIE DUFFIN, KRYSTAL RENE MILLER, VALERIE SNOW, SALLY WEATHERS

Additional assistance

LAUREN HEINZ, NAOKI OBRYAN, JILL PETTY, FERNANDO PUJALS, TIANA PYER-PEREIRA, ADAM SOTO

Dedicated to the Chicagoans who shared their stories for this book, and to the memory of my mother, Naomi Elizabeth Jackson Petty

VOICE OF WITNESS

McSWEENEYS BOOKS

SAN FRANCISCO

For more information about McSweeneys, see www.mcsweeneys.net

For more information about Voice of Witness, see www.voiceofwitness.org

Copyright 2013 McSweeneys and Voice of Witness

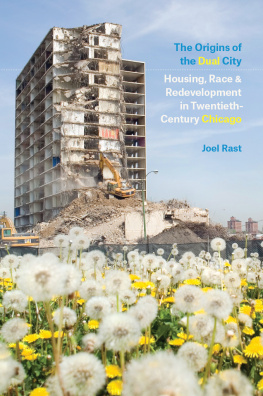

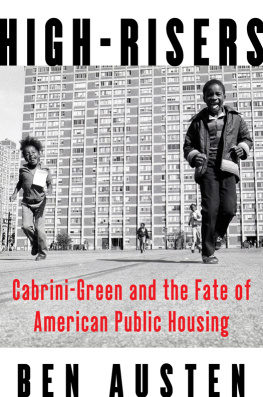

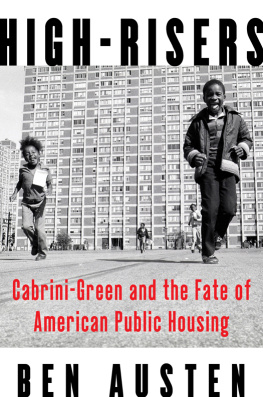

Ben Austens The Last Tower: The Decline and Fall of Public Housing

Copyright 2012 by Harpers Magazine. All rights reserved.

Reproduced from the May 2012 issue by special permission.

Portions of D. Bradford Hunts Blueprint for Disaster:

The Unraveling of Chicago Public Housing

Copyright 2009 by The University of Chicago.

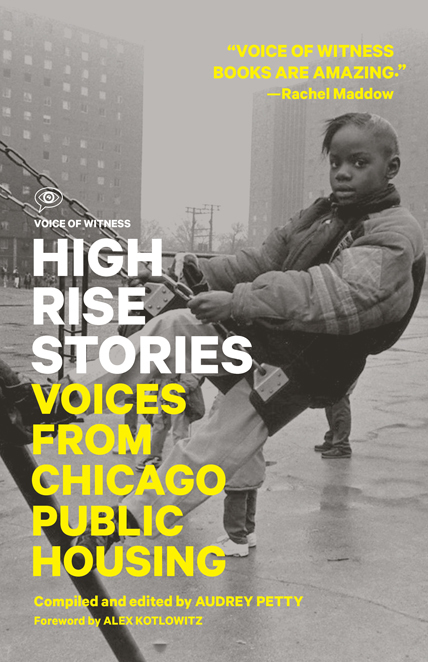

Front cover photo Patricia Evans

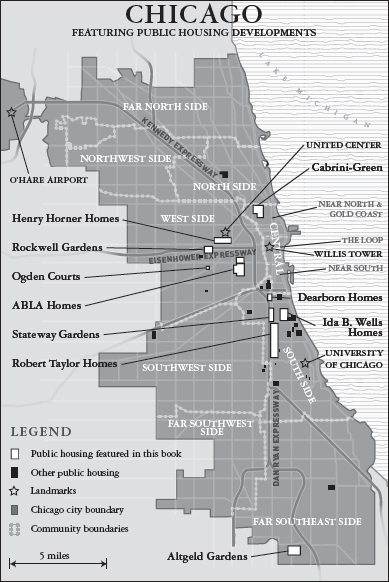

Map and illustrations by Julien Lallemand

All rights reserved, including right of reproduction in whole or part in any form.

McSweeneys and colophon are registered trademarks of McSweeneys Publishing.

ISBN: 978-1-938073-37-3

VOICE OF WITNESS

Voice of Witness is a non-profit organization that uses oral history to illuminate contemporary human rights crises in the U.S. and around the world. Its book series depicts these injustices through the oral histories of the men and women who experience them. The Voice of Witness Education Program brings these stories, and the issues they reflect, into high schools and impacted communities through oral history-based curricula and holistic educator support. Visit www.voiceofwitness.org for more information.

VOICE OF WITNESS BOARD OF DIRECTORS

MIMI LOK

Executive Director & Executive Editor, Voice of Witness

JILL STAUFFER

Assistant Professor of Philosophy; Director of Peace, Justice, and Human Rights Concentration, Haverford College

KRISTINE LEJA

Senior Development Director, Habitat for Humanity, Greater San Francisco

RAJASVINI BHANSALI

Executive Director, International Development Exchange (IDEX)

VOICE OF WITNESS FOUNDING ADVISORS

STUDS TERKEL

Author, Oral Historian

ROGER COHN

Executive Editor, Yale Environment 360; former Editor-in-Chief, Mother Jones

MARK DANNER

Author; Professor, UC Berkeley & Bard College

HARRY KREISLER

Executive Director, Institute of International Studies, UC Berkeley

MARTHA MINOW

Dean, Harvard Law School

SAMANTHA POWER

Author; Professor, Founding Executive Director, The Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

JOHN PRENDERGAST

Co-chair, ENOUGH Project; Strategic Advisor, Not On Our Watch

ORVILLE SCHELL

Arthur Ross Director, Asia Society

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN

Author

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & EXECUTIVE EDITOR: mimi lok

FOUNDING EDITORS: Dave Eggers, Lola Vollen

MANAGING EDITOR: Luke Gerwe

EDUCATION PROGRAM DIRECTOR: Cliff Mayotte

EDUCATION PROGRAM ASSOCIATE: Claire Kiefer

DEVELOPMENT & COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR: Juliana Sloane

PUBLICITY & OUTREACH MANAGER: McKenna Stayner

CONTENTS

In 1987, when I first set foot in the Henry Horner Homes, a public housing complex on Chicagos West Side, I tremblednot out of fear, but out of shame. How could it be possible that people in the worlds richest nation lived in such intolerable conditions? How could I not have known? These were places built on the cheap and then outright neglected by the powers-that-be.

Reading the accounts within this book of the physical decay and danger of now demolished high rises, I recall my own first glimpse of non-working elevators that became steel traps, open breezeways that cut through buildings, overheated apartments, caged-in walkways, and overflowing trash chutes. I remember one building at Horner where tenants complained of a stench emanating from the toilets, the odor of rotting meat. And so the Chicago Housing Authority sent workers into the basement where they found carcasses of dead cats and dogs, along with a trove of 2,000 rusting, never-used refrigerators, stoves, and kitchen cabinets that had long ago been forgotten. The high rises were structures simply too massive, too ignored, and too underfunded to become places where people could thrive. Indeed, at times their very existence seemed like a crime against humanity.

Yet heres the other thing about high rise public housing: these were rich, vital neighborhoods. It was, to be sure, an odd paradox. Here were places marked at times by utterly inhuman conditions, and yet residents considered these buildings home. Tenants in the high rises often felt they belonged to somethingthey were among family and friends, and they had neighbors to lean on. Any time of day or night at Horner, there were always people outside. Everywhere. Just hanging out. Playing basketball. Standing in the breezeways gossiping. Repairing cars. Shooting dice. Shooting marbles. Skipping rope. Playing chess. Barbecuing. There was so much activity, so much clamor, that when I would take some of the kids I got to know camping, the quietness of the woods unnerved them. Public housing, for all its physical ruin, was a lively, spirited place, whose residentsat least many of themcould imagine living nowhere else.

All that eventually changed, though. In describing Chicagos high rise projects in their final years I hesitate to use the word community, because by the end, violence had frayed the sense of commonweal for so many residents. Shootings came to define public housing in the media and perhaps contributed more to the razing of the high rises than their sub-standard maintenance. For the residents themselves, the violence left behind both physical and emotional wreckage so deep and so profound it altered lives. Virtually every voice in these pages speaks of having lost a neighbor, friend, or family member to the shootings. Yet even as these voices share stories from lives diminished by neighborhood violence, they still regard the demolition of their former neighborhoodstheir former communitiesas essentially tragic. Its what they knew. For some narrators, its where they came of age. For others, its where they formed lifelong relationships with friends who were fighting the same fights.