This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1957 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

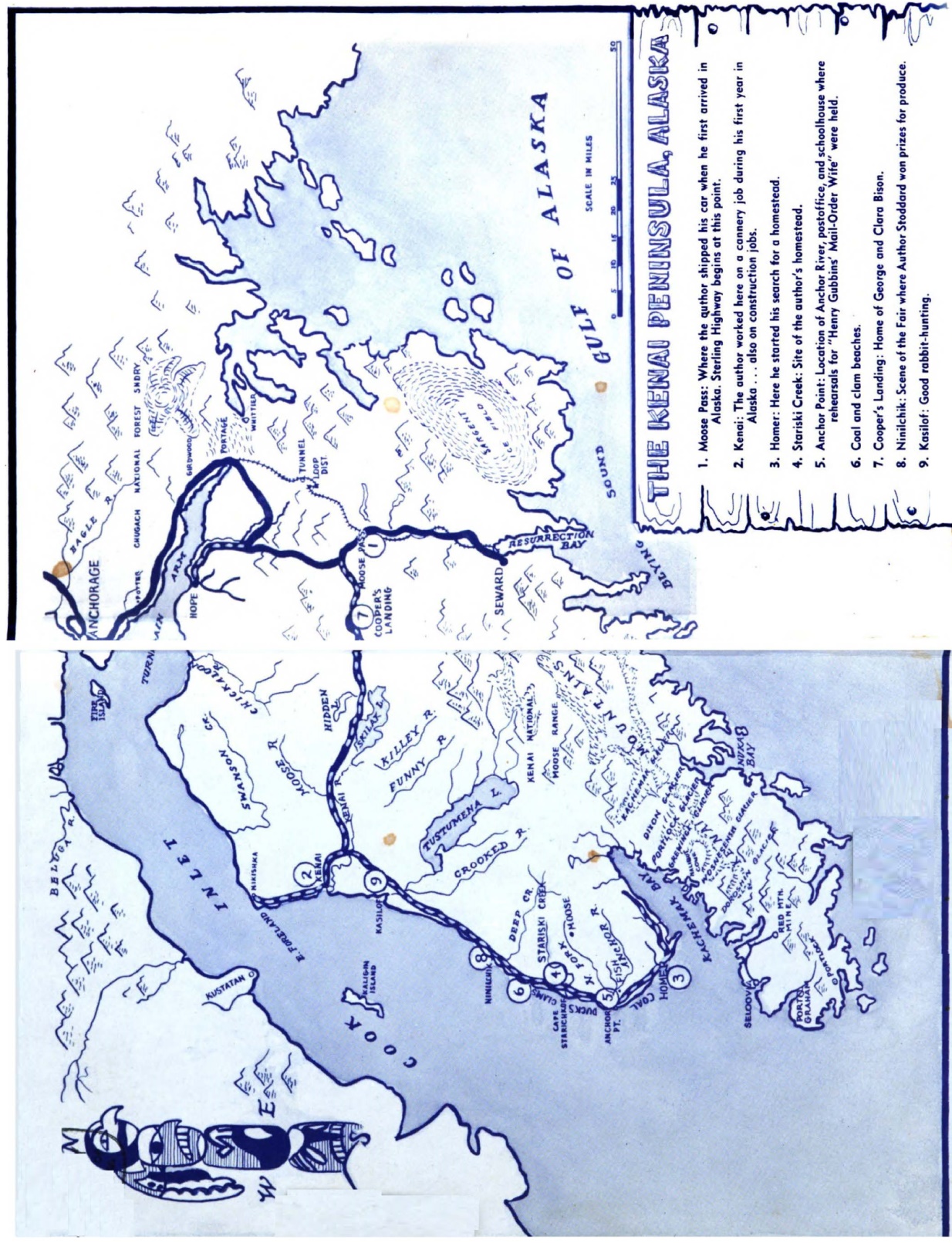

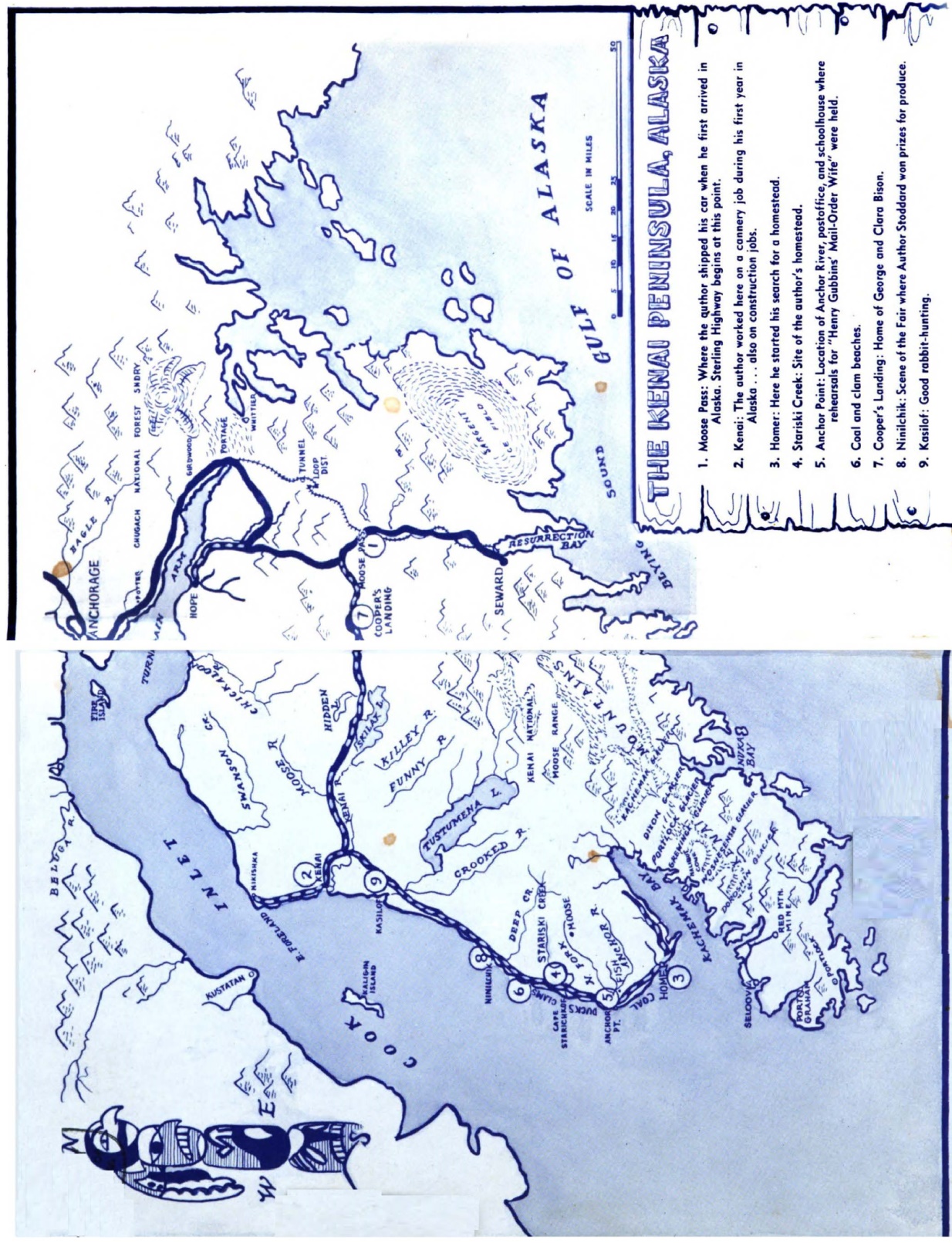

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

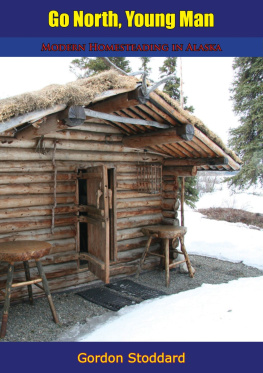

GO NORTH, YOUNG MAN

Modern Homesteading in Alaska

BY

GORDON STODDARD

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Chapter IDont Come Home

DONT COME HOME until youve made good, said my father.

I gulped and stepped on my starter. My last bridge was burning.

But, continued Dad, leaning through the car window and laying an affectionate hand on my shoulder, it you get into trouble or run short of cashdrop me a line. Good old Dad.

We shook handshard. I raced the motor, pulled away from the curb. Dad was still standing there on the sidewalk beside the tall, gray apartment house, his blue suit rumpled in the way it always was, his curly white hair lifting slightly in the stiff morning breeze, when took my last, long look at him in my rear view mirror.

As I wove my way through the traffic of Van Ness Avenue, I wondered what kind of a send-off my fathers father had given him in 1910, when he had headed for the frozen north. Had it been a case of Dont come home then? But he had come home, he had made good. And now I was traveling the same old path. But there was a difference: while my father had ended up in northern British Columbia, I was trying to go him one better by aiming farther northat Alaska.

And there were other differences. My father had left San Francisco with only $58 in his purse; I was starting out with $1200. He had trekked by steamer, on horseback and by dogsled; I was driving an almost-new business coupe which would, I hoped, take me all the way. He was a has-been; I was a 1950 Model Pioneer. Make good? I couldnt help making good!

*****

When I was discharged from the Navy in 1946 I had been like thousands of other ex-G.I.s: restless, switching jobs at a moments notice, starting college and then quitting to try something else, having no definite goal in mind but searching, searching, searching for I didnt know what. I was in a rut. I didnt like cities, I didnt like the pace of post-war life, I was a guy whose greatest joy had always been to get away from it allpreferably with a fishing pole as my only companion beside a high mountain stream. Was I doomed forever to the drab existence of the unhappy commuters I saw rushing past me on the streets?

One day in San Francisco I met a fellow who talked to me about Alaska. Alaskathe last frontier, a place where a veteran could homestead 160 acres and own them in seven months; where a man had to work only six months out of a year to make a good living; where the fish jumped onto your hook without formal invitation and the moose stood still to be shot.

Im a horticulturist, I said. Do you suppose theres any growing land up there?

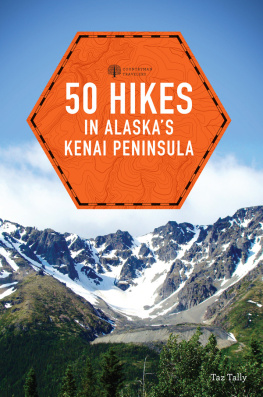

Well, the Matanuska Valleys the agricultural center of the Territory, but thats all taken up. But have you ever heard of the Kenai Peninsula? Its almost as big as California. I hear tell theres a lot of good farming ground there, and its open to homesteaders now.

Thats for me! I shouted. And sending away for pamphlets, books and government bulletins, I had started laying plans.

For two years I had made my preparations. I had gathered all the available information on homesteading, collected maps on the Alcan Highway and Alaska itself, stayed on my job as a plant propagator for a big wholesale-retail nursery, saved my money, bought a new car for the trip, collected equipment I thought I would needa war surplus parka, a crab net, a Coleman stove, and some new fishing gear.

And I had listened to my father. As far back as I could remember he had told me yarns about his conquest of northern British Columbia, of how, as a cheechako, he had created a town, founded a newspaper in a wilderness where he had had to make the news in order to have something to set up in type. I had asked him to tell the stories again, and when I told him of my dream of going to Alaska his enthusiasm had risen to fever pitch. I always knew one of my sons would want to see the north country some day, too, he had chortled. Go to it, boy! You have my blessing!

*****

I stepped on the gas and all 90 horses at my command leaped to obey90, to my fathers one. And as I drove I sang. The tune was an old oneevery California kid sings it from the time he can open his mouthbut the words were my own: Alcan Highway, here I come, right past where Dad started from...

Somewhere around midnight of that daythe date was May 1I hit my first planned stop, Twin Falls, Idaho. I had rushed through California, ignored Nevada: I was a man in a hurry to get to my goal.

Since sleeping in my car as often as possible was a necessity if I didnt want to spend too much money along the wayand I didntI pulled off onto a side road and curled up in my sleeping bag, using the luggage compartment as my bed and the drivers seat, with the back laid flat, as my pillow. In the morning I awoke to find a flat tire on my right rear wheel. After unloading the sleeping bag, extra blankets, Coleman stove, well-stocked grub box, ten gallons of extra gas, five gallons of water, assorted fishing tackle, assorted clothing and my crab net, I managed to reach the spare tire and bumper jack. Then I knew what my father had meant when he said, Better leave all that junk behind, son. When I went north all I took was a bearskin coat and a cocker spaniel pup.

Maybe so, I had replied, grinning. But what was the fur coat for? Thats me: the kidder of the family.

During the next week, in spite of my original haste, I acted like a tourist. When I found a spot I liked, and where the fishing was good, I lingered for awhile. Yellowstone Park was the site of one long stopover, Glacier National Park another. At the latter park it was a couple with a pretty daughter that held me, and the only thing that saved me from lingering longer, and from forgetting all about Alaska and the frozen north, was their sudden departure for the same destination. They promised, as they left, to meet me in the Yukon Territory for some more fishing, but I followed them as far as Calgary, lost them in the traffic and never saw them again. Another roadside romance had gone with the gasbut it had served the purpose of advancing me a few steps closer to my goal.

At Edmonton, Alberta, I was forced to turn all my attention to my driving. The road very rapidly became a morass of dirt, mud, ruts and potholes, sometimes disintegrating into nothing more navigable than a couple of wheel tracks zigzagging haphazardly across somebodys hay field. Gas stations almost entirely disappeared. Flat tires occurred with increasing frequency, and when I stopped to cook a meal on the Coleman stove and grab a few hours of rest, battalions of vicious mosquitoes and clouds of flying bugs fought me for every bite of food, every wink of sleep.

Next page